In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, German restaurants and breweries were popular gathering places in Boston and other US cities. Following the 1848 revolutions and agricultural crises in Europe, German immigration to the United States increased sharply. Although Boston was not a major site of German settlement, the small community that formed here played an outsize role in the development of restaurants and beer gardens in the city. Although their influence waned over time, the German-style beer and foods they served would become part of mainstream American cuisine.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, German restaurants and breweries were popular gathering places in Boston and other US cities. Following the 1848 revolutions and agricultural crises in Europe, German immigration to the United States increased sharply. Although Boston was not a major site of German settlement, the small community that formed here played an outsize role in the development of restaurants and beer gardens in the city. Although their influence waned over time, the German-style beer and foods they served would become part of mainstream American cuisine.

Sauerkraut, Schnitzel, and Socializing

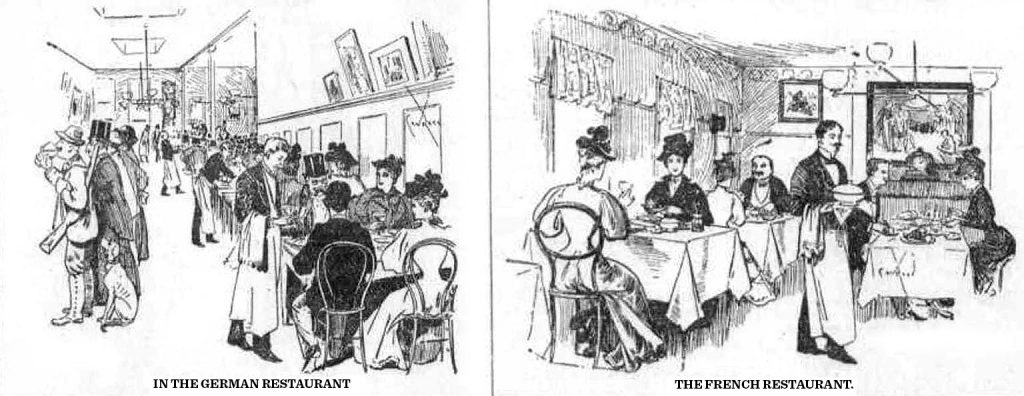

German immigrants began opening restaurants in Boston as early as the 1860s. Most of these restaurants were downtown or in the growing German district of the South End. By 1895, as our map shows, there were at least a dozen German-owned restaurants in this area. An article from the Boston Globe published in 1894 illustrates some of the essential features of German restaurants of the time. As a large part of the German dining experience was centered around socializing and drinking, dining areas were typically spacious, and tables could seat large groups of people.

As the illustration suggests, the entire setting was much more communal and informal than the French restaurant pictured next to it. The German restaurant served a variety of patrons, such as the seated quartet of individuals or the man with hunting gear and his dog next to the bar. Furthermore, many German restaurants welcomed women and families, a rarity in the 19th century when most restaurants serving alcohol were off-limits to women and children. The writer even mentioned that the owner offered him a tour of their wine cellar, noting “the cellar was a kind of revelation, piled to the ceiling on every side with kegs and cases of rare and costly wine.” Such a supply of alcohol was common in German restaurants, and many served lager-style beer supplied by the city’s many German-owned breweries.

Jacob Wirth Restaurant

Founded in 1868, Jacob Wirth exemplifies many of the traditional features of a German restaurant. Its proprietor, Jacob Wirth, was a German immigrant from the wine-growing region of Kreuznach, who worked as a baker before opening his Stuart Street restaurant. Throughout its existence, much of the distinctive menu and decor stayed the same, including its mustard-colored walls, gaslight fixtures, and rugged round tables. Even some of the wait staff worked there for decades. And of course German-style beers and wines were a prime attraction.

The Wirth Company was a family affair, which sustained its longevity. Jacob’s brother, Charles, served as a manager and Jacob’s son, Jacob Jr., was not only born above the restaurant, but was credited with turning it into a “global phenomenon” after his father’s death. Although the family later sold the restaurant, it endured as a German restaurant for 140 years. In 2018, when it closed its door for good, it was the second oldest continuously operated restaurant in the city.

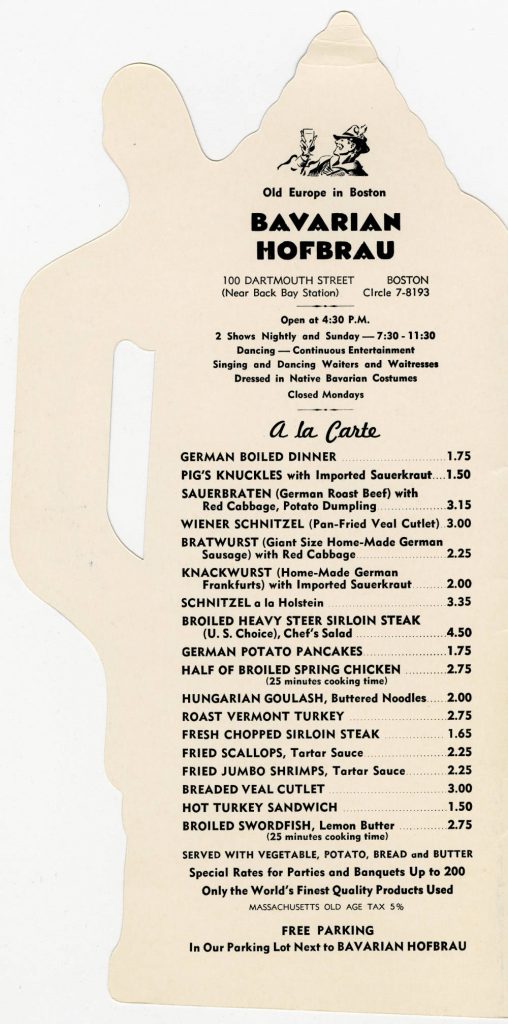

At Wirth and other restaurants, traditional German food was said to be simple and delicious. For starters, there was the herring salad, a “national dish” of Germany. The dish consisted of herring, potatoes, and sometimes pumpkin or other vegetables. Americans, however, tended to prefer the potato salad, which was made special with German walnut oil. Most entrees involved some type of sausage, typically Knackwurst or Bratwurst. Other popular meals included sauerbraten (marinated roast beef) and schnitzel, which was a thin slice of meat (typically veal) that was breaded and fried. Various cuts of fish, steak, and chicken were offered as well.

By the 1920s, German restaurants had spread from downtown to newer areas of German settlement in Roxbury and Jamaica Plain. These neighborhoods attracted German workers and their families employed by local industries, especially the many German breweries that had opened around Stony Brook. In 1926, as our second map indicates, there were at least nine German-owned restaurants in this area. Prior to Prohibition, there were also a few beer gardens operated by the breweries where workers could gather for lunch or after work.

Beer Gardens: Another Expression of German Culture

Beer gardens date back to mid-19th century Bavaria, around the time when Germans began immigrating to the United States. By the 1880s, German-inspired beer gardens began popping up in and around Boston. The beer at these locations was made through traditional German-style brewing, and food and music were equally important. These beer gardens offered a much more inclusive experience than the traditional American saloon. While saloons were generally for men only, beer gardens promoted public drinking and eating as a family affair, where women and children were included in the revelry.

The Summer Bazaar Garden was one of the best known Boston beer gardens in the 1880s, located in the Mechanics Hall building in Back Bay (now the Prudential Center). The Summer Bazaar prized itself not only on its German beer and food, but on its music and entertainment, which featured activities such as billiards, bowling, rifle practice, and skating, along with performances from a military band and full orchestra.

German-style beer gardens even appeared in more congested areas downtown. In 1899, German-born Eugene Selg opened Selg’s Palm Garden near Scollay Square. Inside, the restaurant featured traditional German-style decor and stained glass windows depicting scenes of the homeland. Outside, Selg created a rooftop beer garden that became a popular gathering spot in the warmer months. A 1906 advertisement for the restaurant and beer garden suggested that a visitor would forget “that he is in Puritanical Boston, for the Palm Garden is really a bit of old Germany.” A decade later, however, such places would lose much of their appeal.

The Decline of German Culture: World War I and Prohibition

The World War I years saw a sharp decline in Americans’ interest in German restaurants. Particularly once the US entered the war, increasing xenophobia towards German immigrants and culture led to protests against German food in favor of more “patriotic” options. This antipathy toward German culture resulted in grave consequences for German businesses. Many stopped advertising in local newspapers and flew the American flag on their buildings in order to display their patriotism. Some entrepreneurs even felt compelled to change the German names of their businesses to prove their loyalty to America.

German culture faced another struggle during this time period as Prohibition outlawed the sale of beer, a prominent part of the German restaurant business. One of the key Prohibition advocates, the Anti-Saloon League, used anti-German sentiment aroused by the war to promote Prohibition, arguing that those who opposed it were unpatriotic and were aiding the German enemy. Once Prohibition began in 1920, German restaurants that prided themselves on their selection of beers and wines had to stop selling alcohol. This resulted in a sharp loss in patronage. In fact, Jacob Wirth lost two-thirds of its business during Prohibition and got by selling “near-beer” (with less than 0.5% alcohol) brewed by the nearby Haffenreffer brewery. Although some German restaurants survived Prohibition, a resurgence of anti-German sentiment during World War II led even more to close their doors.

German Restaurants and their Legacy

Over time, German food lost its “ethnic” qualities and became simply “American” food that could be easily found outside of German restaurants. Today, foods such as potato salad, hot dogs, and hamburgers are thought of as American staples, their German roots often ignored or forgotten. A 2015 National Restaurant Association study found that “only 7% of respondents said that they ate German food at least once a month,” which was less than eleven other categories of ethnic cuisine. When the historic Jacob Wirth restaurant closed, the owner explained that a restaurant with “authentic” German food is simply unable to survive today.

Though ethnic German cuisine is no longer as prominent in the city, the demand for German craft ales has shot ‘through the roof’ in recent years and led to the re-emergence of German-inspired beer gardens. Such establishments have popped up all around the city, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, when outdoor drinking and dining spaces provided a safe and enjoyable opportunity to socialize.

Although the heyday of the German restaurant in Boston has passed, German food and drink still hold an important place in residents’ daily lives. Jacob Wirth may be closed, but Bostonians are still engaging with German culture each time they order a hamburger or a craft ale and each time they visit one of Boston’s many beer gardens. Indeed, the story of German restaurants in the US is a prime example of how “ethnic” food has become American fare, displacing the “ethnic” establishments that first introduced it.

–Annalise Durocher, Brian Estes, John Scrimgeour, and Lila Zarrella

Works Cited

“Boston’s Foreign Restaurants: French, Italian, German, Jewish and Chinese Bills of Fare–No Need to Go Around the World to Learn What Others Eat.” Boston Globe, January 7, 1894.

Erby, Kelly. Restaurant Republic: The Rise of Public Dining in Boston. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Judkis, Maura. “‘Grandma’s Food’: How Changing Tastes Are Killing German Restaurants.” Washington Post, March 19, 2018.

McGuinness, Dylan. “The History of Jacob Wirth Co.” Boston Globe, January 18, 2018.

O’Connell, James C. Dining Out in Boston: A Culinary History. Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England, 2016.