Armenians were prominent among the many immigrant workers at the Hood Rubber Company in Watertown, Massachusetts. Courtesy of the Watertown Free Public Library.

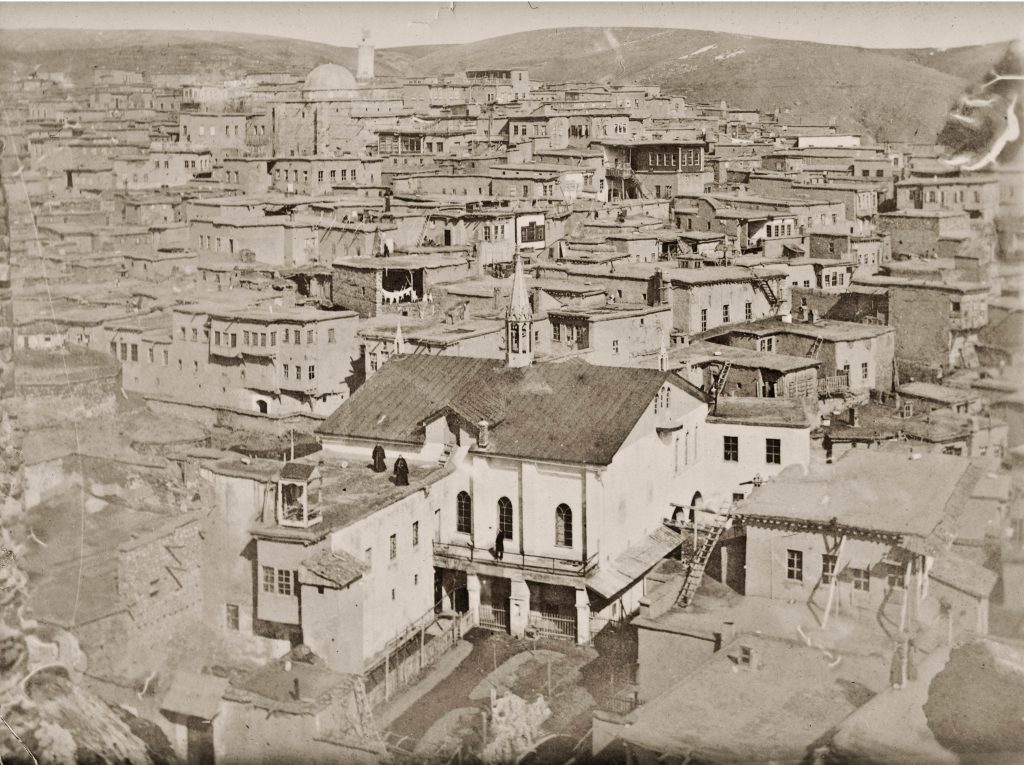

During the nineteenth century, Armenians were scattered across the eastern mountains and plateaus of Anatolia (presentday Turkey). Some had also migrated westward to cities such as Constantinople (Istanbul), Smyrna (Izmir), and Adana. Under Ottoman rulers who regarded them as infidels, Christian Armenians were subject to segregation and oppression that would intensify toward the end of the century.

Contact with the West grew during this period as American Protestant missionaries began opening schools across Anatolia. At the behest of the Americans, a handful of Armenians began arriving in Massachusetts to be trained as clergy at Andover Theological Seminary. Others came as domestic servants for Massachusetts missionaries in the 1860s and 1870s. Before long, they found better-paying work in local industries and began spreading the word to friends and family back home. The largest number of migrants came from the Kharpert Plain, where missionary activity was intense and agricultural and artisanal industries were failing.

Kharpert in Western Armenia, the homeland of many Armenians in Massachusetts, ca. 1915. Project SAVE Armenian Photograph Archives, Watertown, MA.

This migration surged in the 1890s following the widespread massacres of Armenians led by Sultan Abdul Hamid. Hostilities continued in the twentieth century, as the Turks levied steep taxes on agricultural produce and forcibly conscripted Armenians into the Ottoman army. Another round of violence occurred in 1909, when the Turks drove thousands of Armenians from their homes in Adana, killing them or forcing them into exile. But the most horrific violence occurred during World War I when the Ottomans charged the Armenians with treason and slaughtered an estimated 1.5 million people. Most historians agree that the mass violence of 1915-1916 against the Armenian people constituted genocide. It also left tens of thousands of widowed and orphaned refugees who later fled to the United States, the Middle East, and Western Europe.

Armenian immigration to the US dropped off with the restriction measures of the 1920s, but a smaller number of refugees arrived after World War II under the Displaced Persons Act. With the start of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975, ethnic Armenians living in Lebanon fled that country, sending a new wave of migrants to Watertown.

Patterns of Settlement

Following trails blazed by the earlier missionary-led migration, the Boston area became a major center of Armenian settlement. Along with immigrants from Syria, Greece, and China, Armenians initially settled in the South Cove neighborhood then known as “the Orient of Boston” (now Chinatown). During the late 1890s, an Armenian businessman named Moses Gulesian helped to resettle hundreds of refugees from the massacres, housing them in his cornice factory in the South End. Smaller settlements of Armenian workers also sprung up around industries in East Cambridge, Lynn and Chelsea.

The most important destination, however, was Watertown, where the new Hood Rubber factory opened its doors in 1896. Coinciding with the exodus of Armenians from the 1890s massacres, a direct pipeline developed between the Armenian provinces and east Watertown. In the years following the genocide, thousands more arrived. By 1930, there were more than 3500 Armenians living in Watertown—nearly ten percent of the population. In subsequent years, the town would become a major center of Armenian culture and heritage, even as later generations dispersed to surrounding suburbs.

Armenian women workers at M.S. Kondazian Coat Factory, Boston, 1912. Project SAVE Armenian Photograph Archives, Watertown, MA.

Workforce Participation

Prior to 1910, most Armenian immigrants were men who had worked in skilled trades as well as farming and day labor. They had one of the highest literacy rates of any migrant group, with nearly three-quarters able to read in their own language. Nevertheless, in Massachusetts, they took up mostly unskilled and semi-skilled jobs in the shoemaking, textile, rubber and metal industries. In the wake of the massacres and the mass violence of World War I, more Armenian laborers and peasants arrived as well as a growing number of widows with children. Women would thus become a vital part of the workforce at Hood Rubber and other boot, shoe, and garment manufacturers in the Boston area.

From the beginning, Armenians also became entrepreneurs who ran coffeehouses and boarding houses for their countrymen. By the mid-twentieth century, many had left factory work to open tailor shops, groceries, and shoe repair businesses. In greater Boston, Armenian entrepreneurs have been especially prevalent in the rug business and in studio photography. Since World War II, Armenians arriving from the Middle East, Europe and Soviet Armenia have included both educated professionals as well as blue-collar workers.

Sources and Further Reading

Destination Watertown. 2010. DVD. Directed by Roger Hagopian. Watertown, MA: Amaras Art Alliange.

Mirak, Robert. Torn Between Two Lands: Armenians in America, 1890 to World War I. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983.