Thousands rallied in Boston’s Copley Square in January 2017 to protest President Trump’s executive order banning the entry of foreign-born nationals from seven predominantly Muslim countries. Courtesy of Ray Giles.

Although Boston is often described as an immigrant-friendly city, newcomers to the region have periodically faced resentment, hostility, and sometimes violence from native-born residents. Boston was once at the forefront of nativist political movements, and some of its citizens and officials became key architects of immigration restriction and deportation policies. These anti-immigrant, or nativist, sentiments had many sources. They were fueled by economic competition over jobs, housing, and public services, but also by religious, cultural, and political biases. Those beliefs were often intertwined with racist views of immigrants that saw them as debased, immoral, and criminal. Such ideas helped shape national immigration debates and laws that would significantly change the racial/ethnic make-up of Boston and the nation.

Responses to the Irish

Although Boston’s Protestant majority had long distrusted outsiders, the uptick in Irish Catholic migration in the 1830s magnified fears of a Catholic “invasion” that threatened to subvert American democracy in favor of “Popery.” While local preachers and editors inflamed anti-Catholic sentiment from the press and pulpit, working-class Protestants clashed with Irish immigrants in the street. In 1834, an angry crowd of Protestant workmen surrounded the Ursuline Convent in Charlestown and burned it to the ground. Three years later, a dispute between a native-born volunteer fire company and an Irish funeral procession in the North End escalated into a riot in which several Irish residents were beaten and their homes looted and burned.

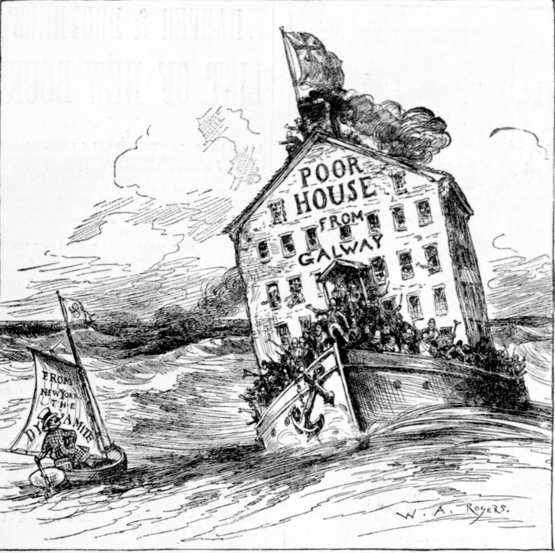

This Harper’s Magazine cartoon by William Allen Rogers suggests that British authorities were emptying the poor houses of Ireland and dumping Irish “paupers” in Boston and other US cities. From: Harper’s Weekly, April 28, 1883.

The surge of Irish immigration spurred by the Great Famine of the 1840s and 1850s heightened nativist feeling and led to widespread discrimination and anti-immigrant political organizing. As labor competition grew, the Irish were excluded from certain jobs and workingmen’s organizations. Anti-Irish sentiment also fueled the formation of the Know Nothings, a secret society so named because its members promised to keep silent about its existence (if asked, they pledged to respond, “I know nothing”). Organized nationally as the American Party, the Know Nothings were strongest in Massachusetts where they controlled nearly all elected state offices by 1854. During this time, nativists disbanded Irish American militia units, barred and deported Irish paupers, required the King James version of the Bible to be read in public schools (which was offensive to Catholics), and established a state literacy requirement for foreign-born voters. Subsequent federal laws governing immigrant restriction and deportation were modeled on the Massachusetts system.

Nativist fervor cooled during the Civil War years, but the economic downturn of the 1870s stirred a new wave of anti-immigrant sentiment–this time toward the Chinese. Fears that the Chinese would undercut American labor gave rise to a violent anti-Chinese movement in the western states, which soon emerged in Boston after Chinese immigrant workers arrived in 1875. Although liberal abolitionists and churches defended the Chinese, many native-born and Irish Bostonians feared the low wages, overcrowded living conditions, and the gambling and opium use that were evident in Chinatown. Growing hostility resulted in passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, a federal law that barred most Chinese from entering the country. Despite this legislation, the hostilities continued as Chinese-owned laundries and other businesses were frequently harassed, and police raids were common in Chinatown. The most dramatic case occurred in 1903 when dozens of police cordoned off the neighborhood and rousted hundreds from their homes and businesses without a warrant. Searching for those who might have entered illegally, police arrested 234 people, 50 of whom were deported. The raid spread fear in Chinatown, and the Chinese population fell over the next decade.

Second Wave Immigrants and the Push for Restriction

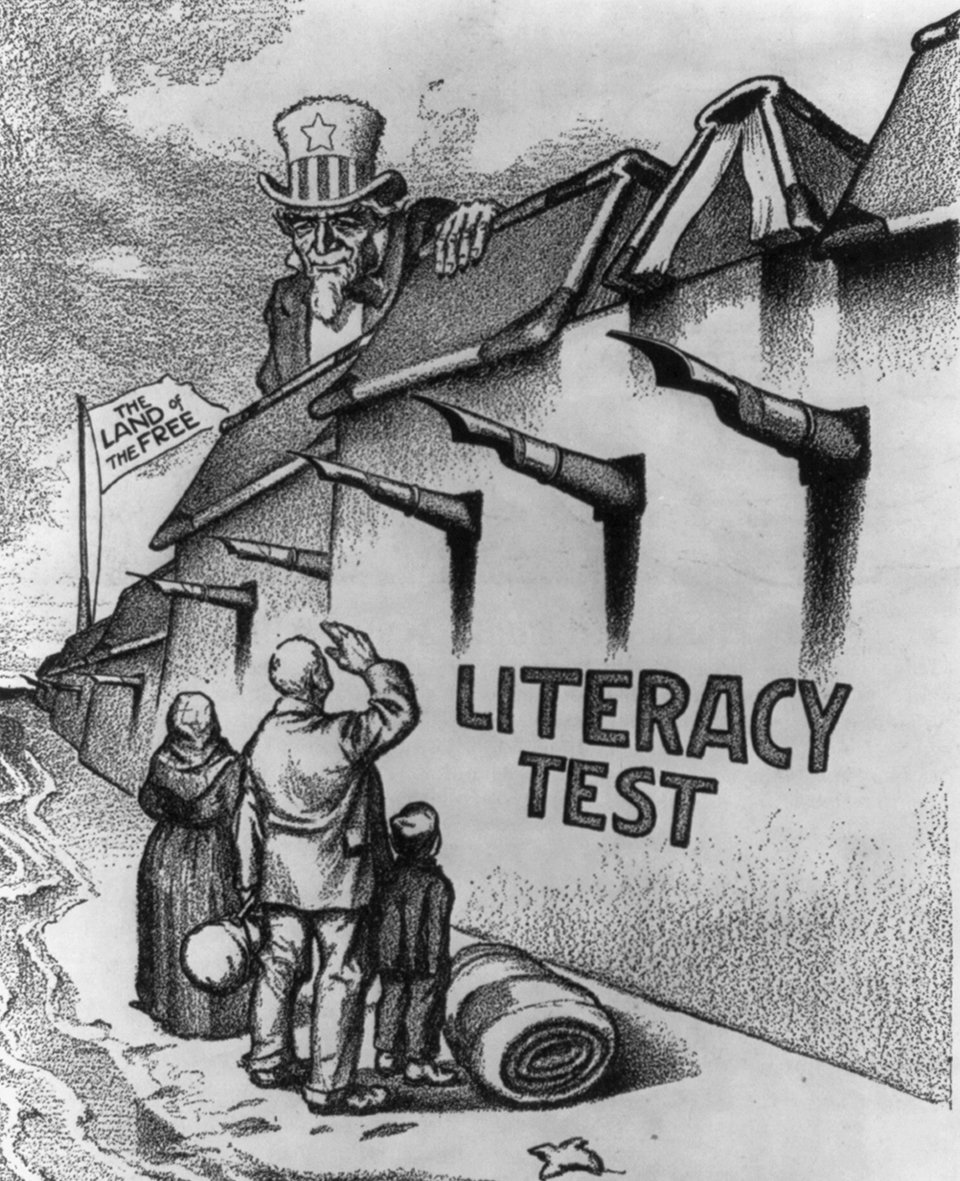

The Boston-based Immigration Restriction League was a key promoter of the 1917 law requiring immigrants to pass a literacy test before entering. This 1916 cartoon depicts the literacy bill as a wall built to keep out undesirable immigrants. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

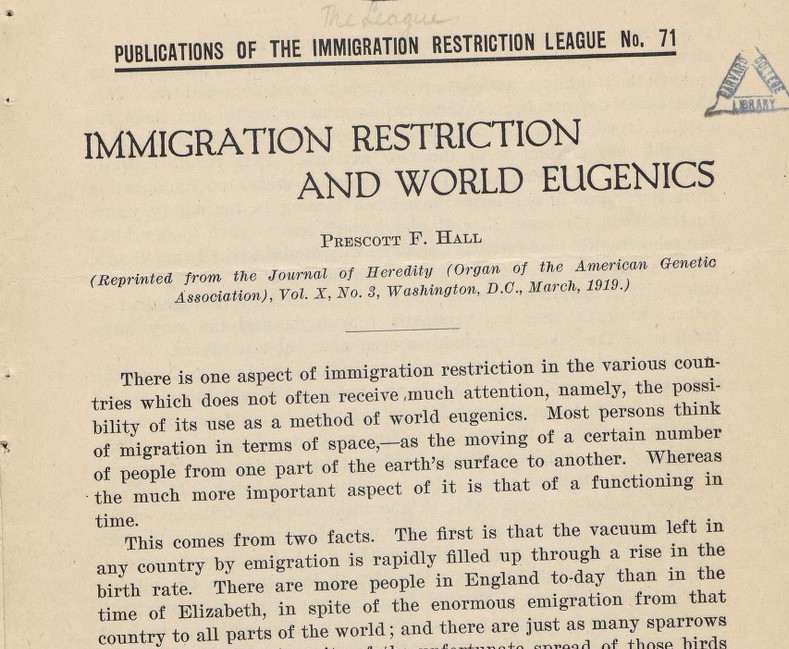

As Boston received a new influx of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe in the late 19th century, Boston nativists looked to more comprehensive immigration restriction as a solution. The objections to these newcomers were similar to earlier complaints about the Irish, but increasingly, nativists used scientific theories like social Darwinism and eugenics to support their claims. Viewing society as a hierarchy of races, nativists relied on flawed scientific ideas that saw new immigrants as inferior and unassimilable. Organizations like the Immigration Restriction League, founded in Boston by three prominent Harvard alumni in 1894, used such ideas to promote restrictive legislation. In 1917, the League was instrumental in getting Congress to pass a literacy requirement for immigrants entering the country.

Xenophobia continued to grow as the US entered World War I, and German immigrants became particularly suspect. German-American organizations were raided, and Karl Muck, the German-born conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO), was widely condemned after the BSO refused to play the Star-Spangled Banner at a concert in 1917. Although he was a Swiss citizen, Muck was later arrested, interned, and deported, as were several other German and Austrian-born members of the BSO.

Italian immigrants also became a target of government repression during and after the war. Looking to round up a militant anarchist group that carried out a series of bombings, the US Justice department led a campaign of raids and deportations that violated due process and terrorized the local Italian community. In 1920, the arrest of two anarchist shoe workers, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, who were accused of robbing and killing two payroll guards in South Braintree, set off an international political controversy. With less than compelling evidence, the two were found guilty and executed in 1927. Although anarchists made up a tiny percentage of the immigrant community, the relentless surveillance and raids of Italian organizations and neighborhoods and the resulting stigma of violence and criminality affected all Italians to some degree.

The anti-immigrant fervor of the 1910s and 1920s culminated in the passage of new legislation restricting immigration. Passed in 1921 and 1924, the laws reduced total immigration by placing an annual cap on the number of entrants and established a national quota system that heavily favored those from northern and western Europe. By 1929, 83 percent of visas went to migrants from that region; southern and eastern Europeans got only 15 percent, while a mere 2 percent were allocated to those from the rest of the world. Asian immigrants, who were ineligible for US citizenship under an earlier law, were effectively barred.

Although immigration declined for several decades thereafter, nativism periodically burst forth in Boston. During World War II, followers of Father Charles Coughlin, a Detroit priest who broadcast an anti-Semitic and pro-fascist radio show, formed a group called the Christian Front. Comprised mostly of young Irish American Catholics, the Boston Front vandalized synagogues and attacked and beat Jews on the streets of Roxbury and Dorchester. Tensions between Irish and Jewish residents in these neighborhoods were longstanding, but recent research suggests that German and British agents also helped foment the violence.

The Era of Global Immigration

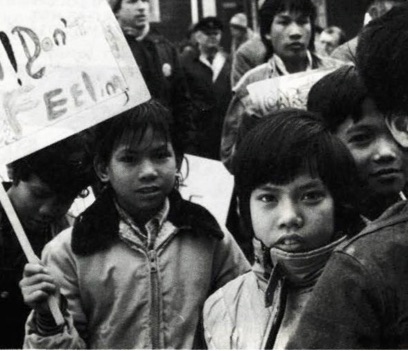

In 1982, Cambodian refugees in Fields Corner moved out of their Westerville Street apartment after ongoing harassment and vandalism (note broken car window). Courtesy of the Boston Globe.

In the postwar era, the percentage of foreign-born in Boston continued to shrink and organized forms of nativism were rare. But after passage of the 1965 Immigration Act, which ended discriminatory quotas and increased global immigration, anti-immigrant sentiments became more prevalent. And given that many new immigrants were people of color, racism played a significant role in the resurgent nativism. Particularly in the wake of the Vietnam war, lingering resentments over that conflict and growing economic dislocations fueled bitter resentments toward Southeast Asian refugees who were being resettled in the Boston area. In the 1980s, three Asian refugees were killed by white assailants and dozens more faced harassment, assaults, vandalism and arson. Other newcomers were also victims of racial violence during these years.

Physical and verbal attacks on Latinos increased in places like Lynn and Chelsea, while a white-Latino riot erupted in nearby Lawrence in 1984. The growing number of undocumented immigrants settling in the metro region in the 1990s stirred opposition among some local residents who felt the newcomers were unfairly taking jobs and benefitting from tax-funded services. After passage of a federal welfare reform bill in 1996, both undocumented and legal resident immigrants lost access to public benefits such as cash assistance, food stamps, and Medicaid. In hopes of reducing illegal immigration, another federal act passed that same year significantly increased the number of detentions, deportations, and family separations.

As these restrictive measures made life more difficult for many immigrants, the tensions and violence of the 1980s also produced local efforts to protect and assist newcomers. Asian American groups organized to support new immigrants across the metro area, and in 1987, the Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition was founded to advocate for immigrant rights and integration. In the city of Boston, the Mayor’s Office for New Bostonians opened its doors in 1998, providing a range of services including legal advice, interpreter services, and resource guides for newcomers in multiple languages.

After the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in 2001, public fears of Muslims escalated, fueling random attacks on those believed to be Muslim or Middle Eastern. Muslim students were interrogated, mosques and Muslim organizations were investigated, and government round-ups of the foreign born shook immigrant communities. In the years since 9/11, numerous efforts at immigration reform have failed in Congress, while detentions and deportations continued to rise. On the other hand, interfaith movements for social justice, immigrant advocacy organizations, and multicultural programs sponsored by local and state governments have worked to reach out to newcomers and mitigate conflict.

With the election of President Donald Trump in 2016, a new level of fear and uncertainty gripped Boston’s immigrant communities. Trump’s travel ban on those from Muslim countries, his statements describing immigrants as “criminals,” the separation of parents and children at the border, and a stepping up of raids and deportations left many fearful and confused. With the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, immigrants were disproportionately affected and their communities suffered significantly higher levels of illness and death. President’s Trump’s repeated statements blaming the virus on China also contributed to a surge in anti-Asian violence in Boston and across the country. Such attacks were not just a byproduct of the pandemic but grow out of a long history of nativism and racism, in which Boston has played a significant part.

Works Cited

Burrage, Melissa. The Karl Muck Scandal: Classical Music and Xenophobia in World War I America. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2019.

Gallagher, Charles R., S.J. The Nazis of Copley Square: A History of the Christian Front. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, forthcoming 2019.

Hirota, Hidetaka. Expelling the Poor: Atlantic Seaboard States and the Origins of American Immigration Policy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Johnson, Marilynn S. The New Bostonians: How Immigrants Have Transformed the Metro Area Since the 1960s. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015.

Norwood, Stephen H. “Marauding Youth and the Christian Front: Antisemitic Violence in Boston and New York During World War II, American Jewish History, Vol. 91:2 (June 2003): 233-67.

Song, Elaine. “To Live in Peace: Responding to Anti-Asian Violence in Boston.” Boston: Asian American Resource Workshop 1987.

Wong, K. Scott. “‘The Eagle Seeks a Helpless Quarry’: Chinatown, the Police, and the Press; The 1903 Boston Chinatown Raid Revisited.” Amerasia Journal 22, no. 3 (1996): 81–103.