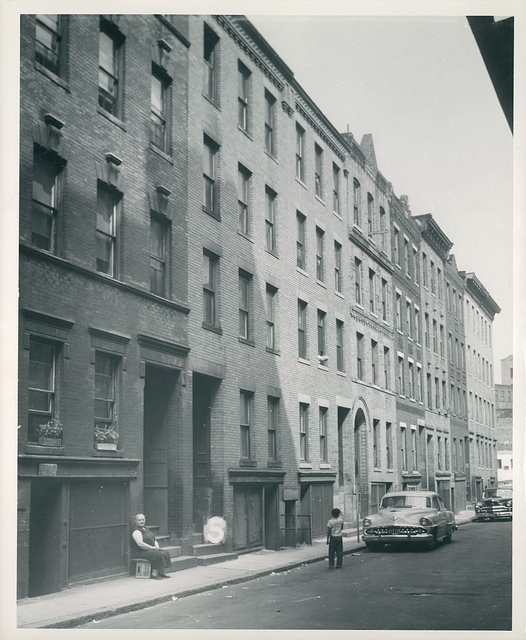

South End street scene from 1903, looking south down Harrison Avenue near the corner of Plympton Street. Courtesy of Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Transfer from the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Social Museum Collection.

Boston’s South End is largely built on landfill in what was originally a tidal marsh. In the early nineteenth century, a strip of land known as the Neck (along presentday Washington Street) was all that connected downtown Boston to Roxbury and the mainland. During the mid-nineteenth century, a series of landfill projects led to the development of dozens of streets and hundreds of fashionable townhouses. Over the next century, the South End would house numerous immigrant groups and become one of the city’s most racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods.

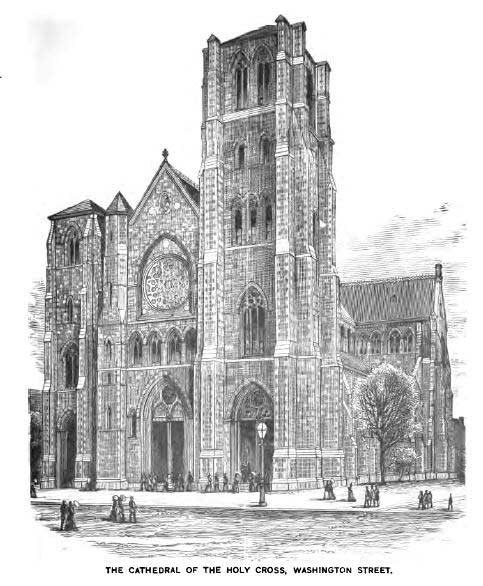

Initially occupied by the Yankee middle class, the neighborhood also hosted smaller numbers of skilled artisans from Germany and Ireland. Catholics from southern Germany raised funds to build Holy Trinity Church on Shawmut Street, which opened in 1875 and would become a center of German life in the city. Central European Jews also lived there as early as the 1840s, bringing their synagogues, Ohabei Shalom and Adath Israel (Temple Israel), from the North End. After the leveling of Fort Hill where many famine-era Irish immigrants lived, the Irish too began moving into the South End. Over the next decade, they helped build and fill the pews at the new Cathedral of the Holy Cross, the center of the Boston Archdiocese that opened in 1875.

With the arrival of new railroads and industries in the neighborhood and the financial Panic of 1873, the South End became less attractive to wealthy Bostonians. Gradually, many began moving to the newly developed Back Bay. Taking their place were growing numbers of poorer immigrants who occupied older homes that had been broken up into tenements and lodging houses. The Irish made up the largest group; most lived in tenements but some became homeowners who took in boarders or ran lodging houses for Irish newcomers. Other lodgers were immigrants from the British Isles and Canadians from Nova Scotia.

By the turn of the century, Jews and Italians had become a significant presence in the South End, especially along Dover (East Berkeley) Street and in the New York Streets (formerly between Albany and Harrison Streets). Many of them worked in local factories and steam laundries or along the docks and railroads that proliferated south of Washington Street. In the early twentieth century, a growing garment district along Harrison Avenue and nearby Chinatown also employed many Jewish and Italian workers.

Moving out from the North End, many immigrants from southern Italy lived in the New York Streets and worshipped at Our Lady of Pompeii on Florence Street, founded in 1902. Jewish residents were also concentrated in the New York Streets and along Dover Street and Harrison Avenue. From the 1890s to the 1930s, they established at least 14 different synagogues in the neighborhood, with congregations from Russia, Poland, Lithuania, and East Prussia. Notable residents included the Jewish writer Mary Antin and Hollywood studio owner Louis Mayer. The South End House and other settlement houses opened around the turn of the century to provide services and help Americanize these newer immigrant groups.

Since the 1890s, male immigrants from the eastern Mediterranean—Syrians, Greeks, and Armenians—had been settling in the adjoining areas of Chinatown and the South Cove, where they worked mainly as peddlers. After World War I, many of these men brought their families and began moving into the South End, opening small shops and lodging houses. As late as the 1970s, Syrian and Greek groceries, bakeries and restaurants could be found along Shawmut Avenue, but most of their patrons had dispersed to the suburbs.

The South End also attracted Africa Americans from the South, who began settling there in the late nineteenth century. The black population grew significantly in the early twentieth century and included newer immigrants from Jamaica and Barbados. Facing widespread discrimination and segregation, these West Indians settled among other black residents in the Crosstown area around Massachusetts and Columbus Avenues. Unwelcome in the local Episcopalian Church, they formed their own congregation, St. Cyprian, which met in a series of local buildings until they built their own church on Tremont Street in the 1920s.

In the years after World War II, suburban flight, disinvestment, and structural deterioration accelerated the decline of the South End. The older immigrant population declined, replaced by a growing black population and new arrivals from Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, who settled around West Newton Street in the 1960s and 1970s. During these years, the city targeted the South End for urban renewal. The first round of redevelopment took place in the 1950s when the city demolished the New York Streets—displacing many Jewish, Italian, and West Indian families. Other parts of the South End were also destined for the wrecking ball. At the same time, development projects in nearby Chinatown/ South Cove also displaced Chinese residents, some of whom moved into nearby streets and housing developments in the South End.

By the late 1960s, black and Puerto Rican residents were fighting displacement through community organizing, public protests, and occupations. One of the fruits of this activism was the building of Villa Victoria, a community-planned and operated housing development in the Puerto Rican section that would become the center of Latino life and culture in the South End. Run by the community development corporation Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción (Puerto Rican Tenants in Action), Villa Victoria has more than five hundred affordable housing units, sponsors a variety of community programs, and hosts the largest Latino arts center in New England.

Since the 1970s, ongoing development projects and rampant gentrification have driven most low-income families and newer immigrants away from the neighborhood. Skyrocketing property values mean that, outside of a few subsidized housing developments, only prosperous immigrant professionals can afford to live there. Although its population is still relatively diverse, the South End now has a somewhat lower percentage of foreign-born residents than the city as a whole.

Works Cited

Green, James. The South End. Boston 200 Corporation, 1975.

History of Holy Trinity (German) Church

Johnson, Violet Showers. The Other Black Bostonians: West Indians in Boston, 1900-1950. Bloomingon: Indiana University Press, 2006.

Lopez, Russ. Boston’s South End: the Clash of Ideas in a Historic Neighborhood. Boston: Shawmut Peninsula Press, 2015.

Woods, Robert A., ed. The City Wilderness: A Settlement Study. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Co., 1898.