There’s an old saying that “when Greek meets Greek, they start a restaurant.” In Boston at least, this seems to have been true. Along with Jews and Italians, Greeks were one the top three immigrant groups that owned restaurants in the city from 1909-1937, as our chart indicates. But unlike Jews and Italians, who each numbered more than 38,000 in Boston in 1920, Greek immigrants had a relatively small presence in the city, accounting for just over three thousand residents, according to the federal Census. Even so, Greek-born entrepreneurs owned more than 350 restaurants in Boston during the 1920s and early thirties. As in New York, Chicago, and other northern cities, Greeks in Boston found restauranteering to be an important, accessible, and economically viable career.

There’s an old saying that “when Greek meets Greek, they start a restaurant.” In Boston at least, this seems to have been true. Along with Jews and Italians, Greeks were one the top three immigrant groups that owned restaurants in the city from 1909-1937, as our chart indicates. But unlike Jews and Italians, who each numbered more than 38,000 in Boston in 1920, Greek immigrants had a relatively small presence in the city, accounting for just over three thousand residents, according to the federal Census. Even so, Greek-born entrepreneurs owned more than 350 restaurants in Boston during the 1920s and early thirties. As in New York, Chicago, and other northern cities, Greeks in Boston found restauranteering to be an important, accessible, and economically viable career.

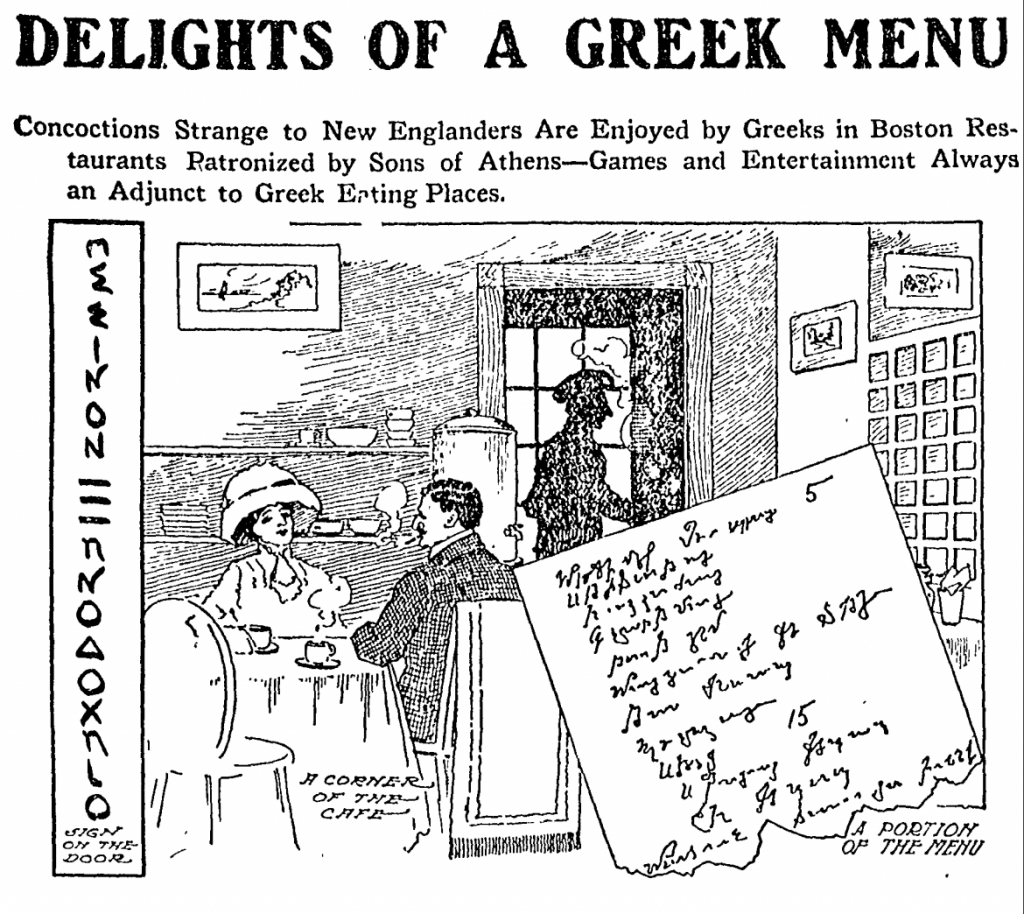

In this 1911 Boston Globe article, the writer explores the local restaurants of Greektown, emphasizing the foreign “delights” of Greek cuisine, along with the use of “unintelligible” Greek on the menus. Boston Globe, May 7, 1911.

Why Greeks have been so overrepresented in the restaurant field is not entirely clear. Some Greek owners started out bussing or washing dishes in restaurants when they first arrived, taking menial jobs that others shunned. As they saved up money, some started their own small restaurants or bought out their employers when they sold or retired. Like other immigrants of this era, Greeks cultivated small businesses as a way of gaining economic independence and avoiding discrimination by the native-born. And like Syrians and Armenians, Greeks had once been part of the Ottoman empire, where they learned to do business with people of many different backgrounds. But clearly, given their small numbers, Greeks in Boston did so to a degree unmatched by other groups.

Restaurants filled crucial needs in the Greek community, in terms of both diet and social life. As a 1906 Boston Herald article noted, “no Greek becomes so much a Bostonian that he does not like to have native dishes for dinner.” Around the turn of the century, the majority of Greek immigrants were single men working to support their families back home and needed a place to congregate and enjoy inexpensive Greek meals. Most of these establishments thus catered initially to Greeks, but soon expanded their appeal to a broader clientele.

Kneeland Street and the Rise of “Greektown”

In early twentieth-century Boston, Greek restaurants were mostly located in the South Cove neighborhood around Kneeland Street. While our 1895 map shows no Greek-owned restaurants in the city, by 1906 the Boston Herald reported that Kneeland Street was home to three Greek restaurants. By the early 1920s, the Greek-American Social Club, a major gathering spot for Greek immigrants, was also located along this strip at 11 Kneeland Street. Newspapers during this time began referring to Greek restaurants not by their name, but by their location on Kneeland Street. Soon the area around Kneeland and Washington streets became known as “Greektown,” the Greek counterpart of neighboring Chinatown to the north and Little Syria to the south.

Likewise, a substantial number of Greek restaurants were located in the North End, where another cluster of Greeks lived among a larger Italian population. During this period, then, Greek restaurants tended to be situated within Greek settlements, creating an enclave for living, eating, and socializing. Taken together, Greek-owned restaurants were highly concentrated in these two neighborhoods. Especially after church on Sundays, these areas were heavily trafficked by Greek men in search of their familiar restaurants, clubs, and coffeehouses. Such restaurants were still in business in the 1920s, as shown on our 1926 map.

Local journalists who visited these restaurants in the early 20th century described them as places where Greek alone was spoken and only traditional Greek foods were served. The menus featured homeland specialties such as avgolemono (a lemony chicken soup), koulouri (a sesame ring-shaped bread), chicken pilaf, a variety of lamb dishes, and baklava for dessert. And visitors were always fascinated by the “famous Greek cheese” (yogurt), which Americans first discovered at these early Greek eateries (though it would not become widely popular until the 1970s). Much of the journalism regarding Greek restaurants at the time centered around the “foreign” aspect of the cuisine. The Boston Globe, for example, noted in 1911 that local Greek eateries included parts of the lamb that were “not considered food by the native New Englander” or that the “salata” would “strike ‘horror’ in the American.”

Temples of Greek Culture

Newspaper articles also commented on the atmosphere of the restaurants and their affinity for Greece and Greek culture. Most eateries were decorated with Greek flags or decorations that highlighted important events in Greek history, typically the Greek War for Independence of 1821-1827. Oftentimes, Greek restaurants would host live entertainment, such as bouzouki (mandolin) players, dancers, or even strong-man acts–the proverbial “Hercules” performances that celebrated Greek masculinity and bravery. Some restaurants and coffeehouses even hosted puppet theater performances that reenacted or celebrated certain moments in Greek history and mythology.

An advertisment for the Marathon Cafe, a Greek restaurant on Eliot (now Stuart) Street in 1920. Boston Herald, February 7, 1920.

American visitors also noted that many restaurants were divided into two separate areas, one for eating and another for lounging and enjoying card games, billiards, and Turkish coffee. The multipurpose nature of Greek restaurants also included games of chance that led to police raids. Gambling was common and legal in Greece, and the heavily male makeup of the early immigrant community proved fertile ground for such activity. In 1921 the Boston police raided the Greek-American Social Club and restaurant on Kneeland Street, arresting 125 people. Other gambling raids occurred in neighboring restaurants along with some in the North End. Such police raids were common in immigrant quarters such as Greektown and Chinatown, and lurid media coverage of them fueled popular associations of immigrants with gambling and crime. Along with the language barrier, these associations limited the appeal of early Greek restaurants for native-born Americans.

Before long, however, Greek restaurant owners began to branch out culturally and geographically. By the 1920s, new establishments had sprung up along Washington and Tremont Streets in the South End to serve the hungry hordes of nearby factory workers. These inexpensive lunchrooms and coffee shops served both Greek and American fare in a no-frills setting (in other cities, they took the form of diners). As our 1926 map shows, there were at least twenty Greek-owned restaurants in the area south of Kneeland Street and north of Massachusetts Avenue. A scattering of Greek eateries also appeared in working-class districts in the West End, Roxbury, and Dorchester.

Athens-Olympia Cafe: A Boston Classic

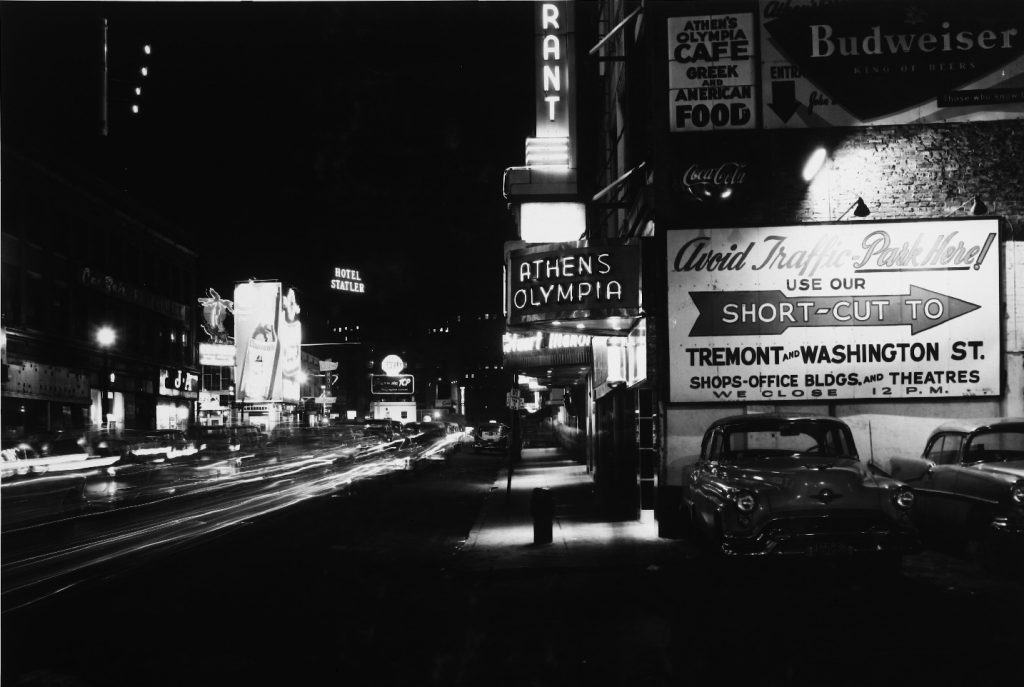

Street view of Athens-Olympia Restaurant at 51 Stuart Street in 1956. Photograph by Nishan Bichajian, courtesy of MIT Libraries.

One of the Greek restaurateurs who was most successful in building a broad customer base was John Cocoris. Starting from humble origins, Cocoris became known as the “King of the Greeks” in Boston because of the wealth and power he derived from his restaurant. Cocoris arrived from Greece in 1905, quickly learned English, and worked as a hotel waiter in Boston and several other cities. Saving much of his earnings, he and a partner opened the Athens Cafe on Washington Street around 1919. The business failed a few years later, but he opened a new restaurant around the corner at 51 Stuart Street in 1927 (adjacent to Jacob Wirth, one of the city’s best-known German restaurants).

Originally called the Olympia Cafe, the restaurant was renamed the Athens-Olympia and served both traditional Greek food as well as more Americanized dishes. Its signature dish was Souvlakia ala Oriental, consisting of lamb on a skewer with onion, pepper, and tomato. The Athens-Olympia became the most famous and popular Greek restaurant in the city, catering to Greek American patrons as well as a wider assortment of business people and theater goers. Isabella Stewart Gardner and Eleanor Roosevelt are said to have dined there, and it was popular with Harvard and other local college students. The Athens-Olympia Cafe remained in business for more than seventy years, closing in 1998.

Today, Greek restaurants are common in the Boston but are scattered throughout the city. In fact, not a single Greek restaurant exists on Kneeland Street, which is now predominantly Asian American. Unlike the turn of the century, these restaurants appeal to a much broader audience, as Americans are no longer “horrified” by the idea of a Greek salad and tend to be familiar with Greek cuisine and its offerings. Moreover, media coverage and general sentiments regarding Greek restaurants differ greatly today from the early twentieth century, when Greek restaurants were known for their associations with gambling and crime. Instead, these restaurants serve as important cultural institutions for Greeks and Bostonians alike, playing a prominent role in the formation of a multiethnic urban culture.

–Kyle Stapleton, Henry Valentine, and Lila Zarrella

Works Cited

“Anagnos was Loyal to Greek Ideals.” Boston Herald, August 5, 1906.

Auffrey, Richard. “Early History of Greek Restaurants in Boston,” Passionate Foodie blog. November 10, 2020.

“Circling the Square: Yaourti and Baklava,” Harvard Crimson, January 22, 1775 [1975].

“Delights of a Greek Menu.” Boston Globe, May 7, 1911.

Moskos, Charles C. Greek Americans, Struggle, and Success. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1989.

O’Connell, James. Dining Out in Boston: A Culinary History. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2017.

“Police Capture 125 in Social Club Raid.” Boston Herald, October 23, 1921.