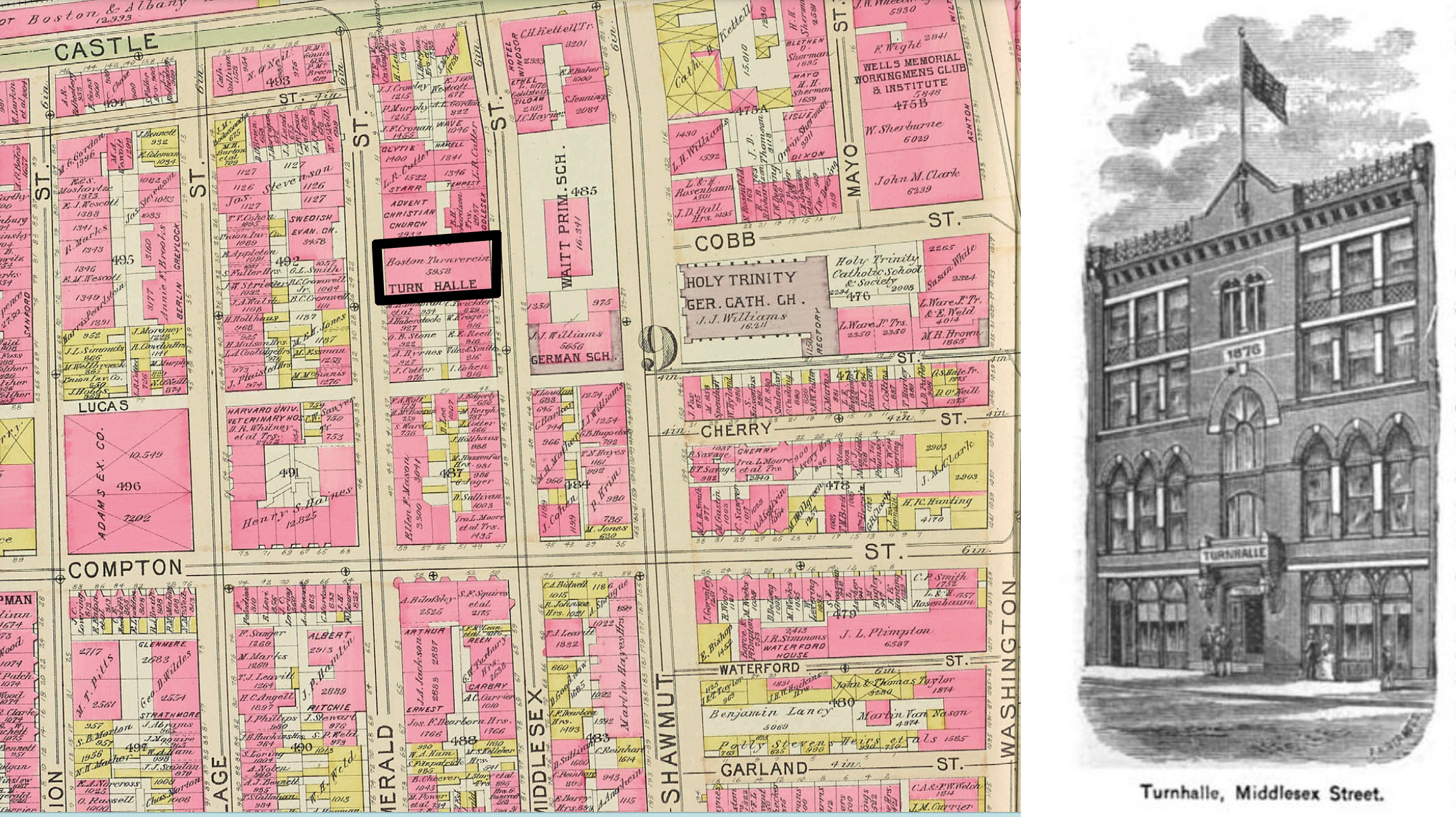

The map on the left shows the German district of the South End in 1895. On the right is the Turnhalle, a community center built in 1876 where German immigrants practiced gymnastics and other sports. Atlas of the City of Boston (Philadelphia: G.W. Bromley and Co., 1895), Plate 15, courtesy of Leventhal Map Center; Turnhalle image from King’s Handbook of Boston (Cambridge MA: Moses King and Co., 1881), 231.

Along with the British, Germans were some of the earliest European arrivals to New England. But the number of German immigrants who eventually settled in Boston was quite small compared to other cities in the Northeast and Midwest. Still, their impact was significant, as they helped shape the city’s cultural, educational, and commercial development. With World War I, however, the German presence in Boston diminished, and migration has remained relatively low ever since.

A small number of German Puritans first came to Massachusetts Bay in 1634, joining English Puritans in a colony governed by their religious faith. Descendants of these families founded the German Society of Boston that would aid the far larger group of German immigrants who began arriving after 1848. Fleeing an agricultural blight and political repression, these newcomers increased Boston’s German population to more than five thousand by 1870. Some of the most prosperous—such as candymaker William Schrafft and publisher Louis Prang—were refugees of the failed democratic revolutions of 1848. Coming at a time before German unification, they came disproportionately from Prussia, Baden, and Bavaria. The majority were Protestants and Catholics, who came in roughly equal numbers, along with a smaller group of Jews.

The city’s German immigrant population continued to grow, peaking around 11,000 in 1900. A dramatic decrease came during and after World War I when wartime restrictions and anti-German hysteria led to a steep decline, a pattern that occurred again during the early 1940s. Immigration ticked up slightly after World War II, but migration from Germany to the Boston area has remained relatively low ever since.

Settlement

As German migration first surged in the 1840s, Boston was rapidly filling in its tidal flats and developing what would soon become the South End. German newcomers settled on these newly laid-out streets, particularly those between Shawmut Avenue and Tremont Street (an area now occupied by the Castle Square Apartment complex). Here along Shawmut Avenue, German migrants founded Holy Trinity, Boston’s German Catholic parish in 1844, while Protestants built the German Evangelical Zion Church in 1847. The popular German Turner movement promoting physical and cultural education also took hold in this area. When the Turner Hall opened in 1876, it quickly became a center for gymnastics but also featured a theater, library, and restaurant serving its German patrons.

Built in 1847 by the city’s German Lutheran community, the Zion Church was located in the city’s thriving German neighborhood in the South End. It held services there in German for more than forty years. As Syrian and Armenian immigrants moved into the neighborhood in the early 20th century, the building became home to an Armenian society, and later to the Sahara, a Syrian restaurant owned by Armenians from 1965-1972. Since then, the building has been largely abandoned–it’s history as a pillar of the German community largely forgotten.

In the late 19th century, more prosperous Germans were moving out to Roxbury and Jamaica Plain (JP), founding successful breweries and other businesses. German workers followed, and by 1910, JP had the largest German community in the city, followed by Mission Hill, Roslindale, and West Roxbury. With its cluster of breweries, JP and Mission Hill became home to many skilled German brewery workers and their families who settled on streets named after Mozart, Schiller, and Bismarck. After World War I, Germans and their children moved further south to places like Roslindale and West Roxbury and increasingly toward the suburbs.

Workforce Participation

Until World War I, Germans in Boston were generally welcomed and could be found in a wide array of occupations. The breweries were the most famous German-owned businesses, and brewery owners such as Henry and Jacob Pfaff, Gottlieb Burkhardt, and Rudolph Haffenreffer employed hundreds of their countrymen in their beer making operations in JP and Roxbury. Germans entrepreneurs also founded department stores, ran printing businesses, and became candy and toy manufacturers. They were even more prevalent in small business, owning a multitude of German restaurants, bakeries, and butcher shops across the city.

Music also proved to be an important livelihood for Germans in Boston. The Germania Musical Society helped popularize symphonic music in the city in the 1850s, and a German-born music teacher, Julius Eichberg, helped introduce musical education to the city’s public schools in 1869. Germans also took the lead in the music publishing industry and were well represented among local instrument makers. In the 1880s, when Henry Higginson organized the Boston Symphony Orchestra, he recruited German and Austrian musicians and conductors. Among them were Karl Muck and Max Fiedler, German-born conductors who led the BSO from 1906-1918.

While German immigrants prospered in a variety of occupations, World War I proved to be a major turning point. Once the US entered the war in 1917, rising anti-German sentiment spurred false accusations of spying against local Germans, including prominent educators, business owners, and even waiters in German restaurants. Yellow paint was splashed on German churches, schools, and businesses, and many of the latter saw a sharp drop in patronage. In response, many German-Americans stopped speaking and teaching the German language and even changed their German-sounding names. Moreover, the onset of national Prohibition in 1919 sealed the fate of many German-owned breweries and restaurants, driving them permanently out of business.

In recent decades, Germans have who have settled in the Boston area have come mainly for employment or because they are married to US citizens. Working in fields such as education, medicine, and information technology, these migrants have relatively high levels of education and household income. Unlike many earlier migrants, they are widely dispersed across the region and well-integrated into local economic and cultural life.

–Marilynn Johnson

Sources and Further Reading

Auffrey, Richard. “Closed for Nearly 50 Years: A History of the Sahara Syrian Restaurant,” The Passionate Foodie, September 4, 2020.

Burrage, Melissa. The Karl Muck Scandal: Classical Music and Xenophobia in World War I America. Rochester, New York: University of Rochester Press, 2019.

Goethe Society of New England. Germans in Boston. Boston: Goethe Society of New England, 1981.

Lurix, Karl A. “The German Lutherans in Boston,” Concordia Historical Institute Quarterly, Vol. 54 (Winter 1981): 146-62.

Nishida, Masayo. “Migrants of Choice: Contemporary German and Japanese Professionals Living in the United States,” Ph.D. diss. Boston University, 2008.

Sauer, Robert J. Holy Trinity German Catholic Church of Boston: A Way of Life (Boston: Holy Trinity German Parish, 1994).