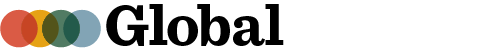

Postcard showing Dorchester Avenue near the corner of Savin Hill Avenue, ca 1913. Courtesy of the Dorchester Historical Society.

Puritans began settling in Dorchester in 1630, many of them coming from Dorsetshire, England, which inspired the town’s name. Their first houses and a fort were built in the Savin Hill area, along what would become Pleasant Street. Later settlements developed in what is now Field’s Corner and Mattapan Square.

During the mid-1800s, an influx of Irish Catholic immigrants changed the ethnic and religious makeup of the area, particularly in the northern end of Dorchester closest to Boston and along the Neponset River where a chocolate factory and other mills offered employment. Efforts to build a Catholic Church in Dorchester met significant resistance from native-born Protestant residents. In 1854, a partially constructed church building in Lower Mills was destroyed in a fire that many believed was set by the Know-Nothings, a nativist political group. Eight years later, the Boston Archdiocese established St. Gregory parish in the same area, and a new church building was erected in 1863.

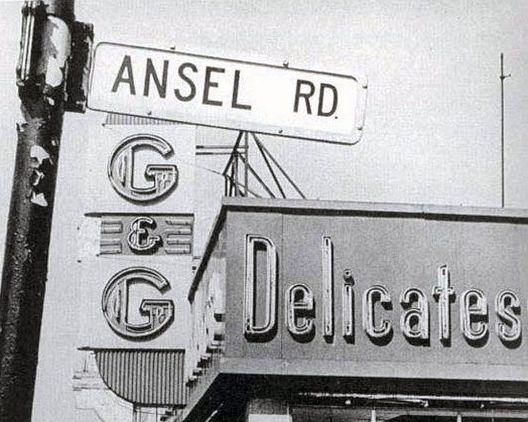

St. Peter Catholic Church in Meeting House Hill, ca. 1915, a predominantly Irish-Catholic parish at the time. Courtesy of the Dorchester Historical Society.

Over the course of the 19th century, Dorchester’s growing population transformed the region from farmland into a more suburban environment, attracting migrants who needed access to the city. In the 1830s and 1840s, the Boston & Providence and Old Colony railroad lines came to Dorchester, and in 1857, an electric tram service made Dorchester a “streetcar suburb,” spurring the construction of single-family homes. In 1870, the City of Boston annexed the town of Dorchester, and its population would surge from 12,000 to more than 100,000 by the early 20th century.

Around this time, a second Catholic parish, St. Peter, was established to serve the growing Catholic immigrant communities of north Dorchester. The construction of St. Peter’s church in Meeting House Hill began in 1872 and was spearheaded by Father Peter Rowan, an Irish immigrant who raised building funds from nearby Irish female domestics, along with financial contributions from their non-Catholic employers. The huge gothic church, topped by a grand tower, seated more than a thousand and could be seen for miles around. In the ensuing decades, the parish built a rectory, school, and convent and spun off several other Catholic parishes including St. Margaret, St. Leo, and St. Paul.

Beginning in the 1890s, triple decker residences became common in Dorchester. Generally built along the streetcar lines, these structures appealed to builders because they cost considerably less than other dwellings. Italian, Irish, Polish, and Jewish immigrants all lived in these multi-family dwellings, and by 1910 the foreign born made up 27 percent of Dorchester’s population. Immigrants from Ireland, Canada, and Russia (mainly Jews) made up the largest percentages, respectively. The foreign-born population continued to grow for the next twenty years, peaking at 30 percent in 1930, with notable increases in Italians, Poles, and Lithuanians.

Blue Hill Avenue near Columbia Road, 1949. Located in the heart of Jewish Dorchester, the Franklin Park Theater originally featured Yiddish productions but later became a popular movie theater. Courtesy of Boston City Archives.

Around the turn of the century, many Italians moved away from the North End to Dorchester, while others came directly from Italy. They gathered around Quincy, Dacia, and Dove Streets, with some also residing along Norfolk Avenue and Willow Court. Beginning in the 1890s, Jews also moved out of the older downtown districts. They settled along Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester and Upper Roxbury, alongside a small but growing African American population. In 1912, a group of Jewish families built Dorchester’s first synagogue, Beth El, located on Fowler Street in the Mount Bowdoin district. By the 1920s, there were at least 25 synagogues serving Dorchester’s booming Jewish population.

After World War II, Dorchester experienced continuous and radical demographic changes. Dorchester Jews left for the suburbs of Brookline and Newton, following their synagogues, which could relocate relatively easily. Others were motivated to move when the Boston Banks Urban Renewal Group removed racial restrictions on mortgage lending to black buyers in 1968, which led to block busting and racial turnover in the area. Irish American and other white ethnic groups also left Dorchester during these years, but did so more slowly because of ties to local Catholic parishes that could not relocate. By the time new waves of immigrants began to call Boston home in the 1960s and 1970s, many former Jewish neighborhoods in Dorchester were now predominantly Black.

New immigrant groups began to migrate more steadily into the Boston area following the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which facilitated migration by dissolving discriminatory quotas. Dorchester became a key receiving area for groups such as Haitians, Cape Verdeans, West Indians, Dominicans, and Vietnamese. By 2015, these New Bostonians–predominantly people of color–constituted more than a third of Dorchester’s population.

Haitians along Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester awaiting the Haitian Flag Day Parade, 2016. Photo by Gage Norris.

Spurred by political repression at home, Haitians were one of the earliest groups to arrive and formed a significant community in the Dorchester/Mattapan area by the 1970s. The growth of the immigrant community animated the establishment of resources like the Codman Square Health Center and culturally specific organizations like the Haitian Multi-Service Center and the Association of Haitian Women. Haitian immigrants were largely unified by their dominant Catholic faith, filling local churches such as St. Leo and St. Matthew in the Franklin Field and Codman Square districts. This unifying influence is still noticeable today in the community’s standing tradition of enrolling Haitian children in local parochial schools.

In the 1980s, a growing Vietnamese refugee population also moved to Dorchester. Originally settling in Chinatown and Allston-Brighton, many Vietnamese moved to Fields Corner as rents in other parts of the city were becoming unaffordable. Fields Corner became a stronghold of the Vietnamese community, and restaurants, businesses and community organizations like VietAID helped provide products and services and worked to preserve Vietnamese culture through classes, cultural programs, and festivals.

The Cape Verdean community is one of the more recent immigrant groups to come to Dorchester. Starting to move slowly into the community in 1975, it was not until the 1980s that Uphams Corner started to see a demographic shift. By 2016, 60 percent of Boston’s Cape Verdean immigrants lived in Dorchester. The neighborhood is also home to a large number of Dominican and West Indian residents. All of these groups moved to Dorchester because of its affordability and proceeded to found ethnic churches, restaurants, and other small businesses.

Since its founding in the 17th century, Dorchester has acted as a major receiving area for immigrants of various national origins and religions. The neighborhood today is filled with institutions and organizations that reflect this ongoing diversity. While prominent immigrant communities continue to thrive within Dorchester’s corners and squares, more upwardly mobile newcomers have begun to leave the neighborhood for suburbs like Randolph, Milton, Quincy, and Brockton. This, along with recent gentrification and a rising cost of living, suggest that the faces of Dorchester will continue to change.

Research and writing for this profile was the work of students in Professor Marilynn Johnson’s Contested Cities Seminar in the History Department at Boston College in 2018. For more on the history of specific immigrant groups in Dorchester, please click on the feature boxes below.

Works Cited

Boston 200 Neighborhood History Series. Dorchester. Boston: 1976.

Gamm, Gerald H. Urban Exodus: Why the Jews Left Boston and the Catholics Stayed. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Jackson, Regine O. “After the Exodus: The New Catholics in Boston’s Old Ethnic Neighborhoods.” Religion and American Culture 17 (Summer 2007): 191–212.

Kennedy, Albert J., and Robert Archey Woods. The Zone of Emergence: Observations of the Lower Middle and Upper Working Class Communities of Boston, 1905-1914. 2d ed. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1969.

Lui, Michael, and Shauna Lo. Vietnamese Americans in Fields Corner. Institute for Asian American Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston. 2018.

Sammarco, Anthony M. The Baker Chocolate Company: A Sweet History. Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

Sarna, Jonathan D. and Ellen Smith. The Jews of Boston. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2005.