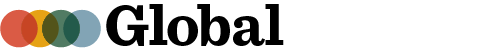

Postcard of Harvard Avenue in Allston Village, between Commonwealth and Brighton Avenues, 1921. Courtesy of the Brighton Allston Historical Society.

While immigration has long been a part of Allston-Brighton’s history, the rise and fall of the cattle industry has been a defining feature of life in these neighborhoods. Before 1807, the two interlocking neighborhoods now known as Allston-Brighton belonged to the town of Cambridge and carried the moniker “Little Cambridge.” When the Continental Army was headquartered in Cambridge before the British evacuation of Boston, George Washington contracted with the Winship family across the Charles River to supply his troops with beef. By the time Little Cambridge separated to form the new town of Brighton, the Winships held the title of largest meatpackers in Massachusetts.

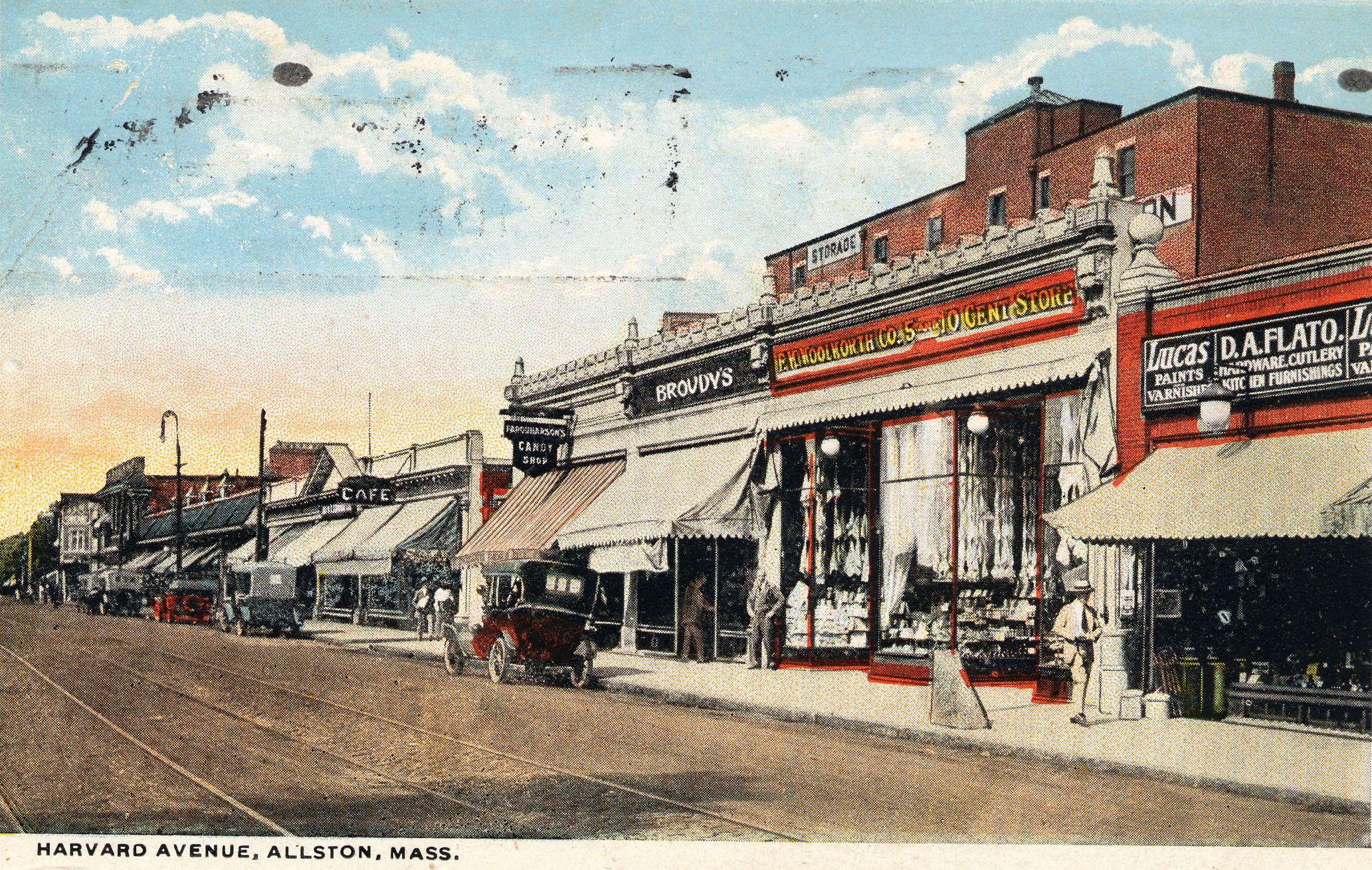

Above: Abattoir workers, many of whom were Irish immigrants, undated. Below: The Brighton Stock Yards on North Beacon Street, 1950s. Courtesy of the Brighton Allston Historical Society.

As Irish immigrants flooded the area at mid-century, they found work in the multitude of jobs available in Brighton’s cattle industry, including droving, farming, slaughtering, and rendering of animal by-products. The Irish presence spurred the founding of Brighton’s first Catholic church in 1855, St. Columba’s—later St. Columbkille. As hundreds of thousands of cattle, hogs, and sheep arrived each year for slaughter, fears grew that the sprawling meatpacking operations posed a threat to public health. In 1872 the Butcher’s Slaughtering and Melting Association gathered the many slaughterhouses into the Brighton Abattoir, a large scale facility built along the Charles River at the corner of Market and Arsenal Streets. The stockyards moved to nearby North Beacon Street in 1884.

This consolidation of cattle industry functions freed up land for residential building in Brighton, most of which turned into housing for the Irish immigrants who dominated the livestock and slaughtering trades, hotel and saloon keeping, small-scale manufacturing, and local politics. Italians, many of whom congregated around Oak Square and Lower Allston, boasted the second-largest immigrant group around the turn-of-the-century. Although the Lebanon Kosher Wurst Company occupied a section of the abattoir for kosher slaughtering in 1900, the Jewish population of Brighton would not grow to substantial numbers until the postwar years (from 1200 in 1920 to 13,000 in 1950), as evidenced by the 1948 establishment of a Brookline-Brighton-Newton Jewish Community Center in Brighton. Some were newly arrived refugees, but others came from the declining Jewish sections of Dorchester and Mattapan.

The Brighton Abattoir was demolished in the 1950s, and the stockyards closed in 1967. Around the same time as the cattle industry exited, Allston-Brighton’s white middle-class residents were moving to suburbs farther away from the city. The new residents came from two separate backgrounds: students from the three abutting universities—Harvard University, Boston University, and Boston College—and new immigrants from a myriad of countries coming for about as many different reasons.

In the 1980s, the majority of new immigrants were Spanish speakers from Central America. The rest spoke French, Portuguese, Chinese, Russian, and other Asian languages. By 1985, 30 percent of Boston’s Asian population lived in Allston-Brighton, which totaled 12 percent of the neighborhoods’ residents. Many of the Chinese immigrants there had relocated from Chinatown, where urban redevelopment had demolished hundreds of apartments and businesses.

Several other groups fled their countries and came to Allston-Brighton as refugees. Since the late 1970s, Haitians came to escape the political and economic hardships in Haiti, while Cambodians and Vietnamese arrived in Allston-Brighton under refugee programs following the Vietnam war. Since the 1980s, Soviet Jewish refugees have also settled in the neighborhood in large numbers, making Russian and Ukrainian grocery stores a common sight along Harvard and Commonwealth Avenues.

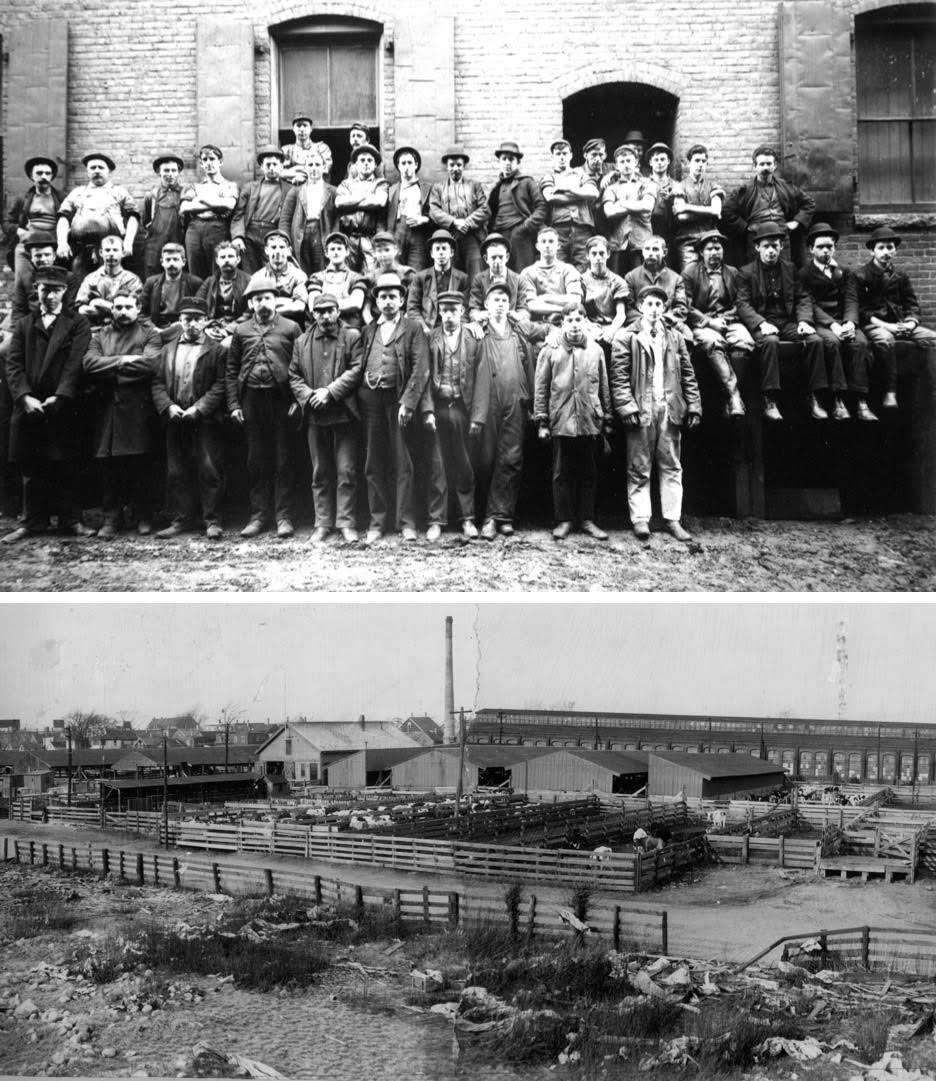

A Brazilian drum band, Bloco AfroBrazil, performs on Harvard Avenue in Allston, 2012. Courtesy Allston Street Fair.

As of 2010, the three largest immigrant groups in Allston-Brighton were Chinese, Brazilian, and Russian. Brazilians started arriving in greater numbers in the 1980s in response to inflation and unemployment in their homeland, and according to the Boston Globe in 1989, were “highly visible at several locations, including BU’s Malvern Field where between 50 and 100 Brazilians regularly play soccer on Sundays.” By the late 1990s, St. Anthony’s Church, built in 1895 to minister to the Irish and Italian butchers and stockyard workers of Lower Allston, claimed a sizable Brazilian community.

Allston-Brighton’s foreign-born population peaked in the early 21st century, making up more than 30 percent of the total population. By 2016, it had fallen to 26 percent, likely because of growing student populations, rising housing costs, and gentrification. Despite their shrinking numbers, the foreign-born of Allston-Brighton remain visible on the streetscape with the vast number and variety of ethnic food shops and stores along Harvard and Brighton Avenues. Chinese, Brazilian, and Mexican businesses still maintain a presence, but Koreans now dominate the street: one-third of Boston’s Korean population lives in Allston-Brighton, a 54 percent increase from the previous decade. Immigrants, an essential part of Allston-Brighton’s workforce and community since the cattle industry days, thus continue to power and stabilize the community.

–Madeline Webster

Works Cited:

Brighton Allston Historical Society, “Brighton Allston Cattle Industry,” http://www.bahistory.org/CattleIndustry.html.

Marchione, William P. Allston-Brighton in Transition: From Cattle Town to Streetcar Suburb. The History Press, 2007.

Mishkin, Linda. Legendary Locals of Allston-Brighton. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2013.

Robichaud, Andrew. “Brighton Fair: The Life, Death, and Legacy of an Animal Suburb.” Journal of Urban History 48, no. 3 (2022) 638-56.

Sarna, Jonathan D, Ellen Smith, and Scott-Martin Kosofsky. The Jews of Boston. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

Smith, David C. and Anne E. Bridges. “The Brighton Market: Feeding Nineteenth-Century Boston.” Agricultural History 56, no. 1 (1982): 3-21.