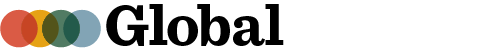

Ohel Jacob (shown here ca. 1898), was East Boston’s oldest and largest synagogue, located on the corner of Paris and Gove Streets. Formerly an Episcopal church, Ohel Jacob was founded in 1893. The congregation built a new synagogue on the site in 1905, which was destroyed in a fire in 1973. Courtesy Jewish Heritage Center at the New England Historic Genealogical Society.

Eastern European and Russian Jewish immigrants began arriving in East Boston in large numbers in the 1890s, reaching a peak population of around five thousand in the 1910s and then declining and nearly disappearing after World War II. During the first years of the twentieth century, East Boston had what may have been the largest Jewish community in New England. Bringing religious and cultural traditions from their homelands, the Jews of East Boston established synagogues, schools, and social organizations that helped support them in a sometimes hostile environment.

Migration

The majority of the Jews in East Boston came from the Russian empire that included large parts of Eastern Europe. Fleeing anti-Semitic laws and violence as well as a lack of economic opportunities, the Jews came from the Pale of Settlement, the only region in imperial Russia where they were allowed to live. A sample of World War I draft registration cards from East Boston indicates that Jewish immigrants came mainly from large cities such as Kovno and Vilna (Lithuania), Odessa (Ukraine), Warsaw (Poland), and Minsk (Belarus).

As Jews could not obtain passports in Russia, many were forced to seek help from Prussian smugglers who did a thriving business helping them cross the border. From Prussia they went to Berlin or Hamburg where they boarded ships directly to Boston or to Boston via Liverpool. In many cases, the male head of the family left first and then brought over wife and children, and sometimes siblings, parents and in-laws. The federal Census of 1910 tell us that many Jews in East Boston lived with their close relatives such as parents, in-laws, uncles, aunts and cousins.

Settlement

While small numbers of Jews arrived in Boston from Germany and Poland in the mid-nineteenth century, very few of them settled in East Boston. But the neighborhood did become well known among Jews when the Ohabei Shalom synagogue in downtown Boston purchased land in East Boston (near presentday Constitution Beach) in 1844. It soon became the first Jewish cemetery in Boston and a significant landmark for the local Jewish community.

When a larger wave of Russian Jewish immigrants arrived around the turn of the century, many gravitated to East Boston. The majority settled in the area between Bremen and Meridian Streets, replacing the Irish on Bennington and Lexington Streets and in parts of Eagle Hill. Kosher markets, restaurants, and other Jewish businesses took root along Chelsea and Porter Streets. Massachusetts synagogue records show that the synagogues in East Boston were located very close to each other in this same area, where Jews could easily walk to them on the sabbath. This densely populated area further suggests how Jews clustered together to be near each other and their businesses. Moreover, the Jews experienced hostility from both native-born and Irish residents, and early Jewish settlers of the 1890s remember having stones thrown at them by local gangs. Such enclaves were thus both a source of community and self-protection as well as a product of segregation.

Occupations

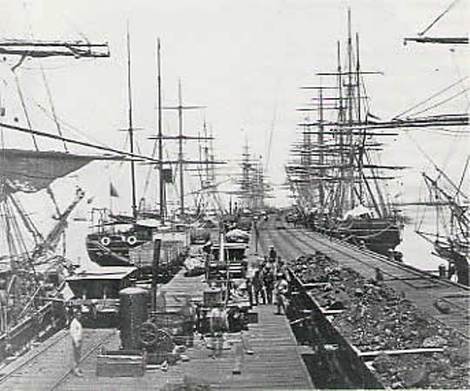

Jewish scrap dealer on Orleans Street, 1914, a common occupation for Jews at the time. Courtesy of the Jewish Cemetery Association of Massachusetts.

The typical Russian Jewish immigrant that arrived at the turn of the century was a literate male with a skilled trade who arrived together with a literate wife and children. Most of the Jews who came to East Boston around 1900 were working class, the majority being small merchants or craftsmen. Many found work opportunities in the clothing, textile, and shoe industries. Census data from East Boston from 1910 tells us that they were tailors, jewelers, scrap dealers, and grocery store owners. Most of the married women did not work, and those who did worked in their husbands’ businesses. The 1910 census indicates that the unmarried women who worked were mainly employed in the clothing business. The new immigrants quickly became successful in the needle trades and some were able to accumulate wealth and open their own small stores.

Among those who settled in East Boston was Benjamin Canner, born in Vilna in 1883 and who came to East Boston as a poor eighteen-year-old boy. In his early twenties he set himself up in the furniture business at 456 Bennington Street, in the heart of the Jewish community. Not many years after that he acquired a large four-story building on the same street near Central Square where he expanded the business.

Iva’s Lunch on Bennington Street, ca. 1946. On the right is Harry Kaplan, his son Ralph (who started Kappy’s Liquors), and an unidentified employee. Courtesy of the Jewish Journal.

Another Jewish immigrant storeowner was Ralph Kaplan’s father. An article from the Jewish Journal depicts Harry Kaplan as a hardworking man who came from Russia around the turn of the century without money and unable to speak English. “About all they brought with them was their heritage and their Judaism,” said his granddaughter Anne. Mr. Kaplan established a home for his family on Lexington Street and worked as a fruit peddler to save up money to buy a cafeteria on Bennington Street. There, he and his brother offered ten-cent lunches and dinners for workers. Ralph worked with his father after two years of studying at Boston University. The family eventually sold the cafeteria and opened a successful liquor store that would later become Kappy’s Wine and Spirits.

The two stories illustrate how some East Boston Jews were able to buy property and own businesses. In The Zone of Emergence, Albert Kennedy claimed that about one third of the neighborhood’s Jews set up as small shopkeepers. They largely occupied businesses different from the majority of the immigrant and native-born population. The orthodox Jewish life contributed to the Jews’ success in the grocery business because they were the only ones who provided kosher food. As a result the competition was limited, but so was their contact with the rest of the society. As other articles from the Jewish Advocate show, East Boston Jews also worked in other Jewish neighborhoods such as the South and North Ends, especially after the completion of the streetcar tunnel to downtown Boston in 1904.

Religious and Cultural Life

Jewish social and cultural life revolved around the synagogues. Congregation Ohel Jacob was the first synagogue founded in East Boston in 1893 on the corner of Paris and Gove Streets. Formerly St. John’s Episcopal Church, the original building was torn down in 1905 and rebuilt as a synagogue the following year. As the Jewish community grew so did the need for synagogues, and by 1913 there were at least four others in East Boston: Beth David, Linath Hazedek, Keser Israel, and Choreh Mismaeth.

Besides organizing religious life in the Jewish community, the synagogues engaged in cultural and political events. They were the centers of Jewish cultural life in East Boston where all marriages, bar mitzvahs, services and rituals took place. In addition, much of the community’s social life was carried out in the various organizations and clubs established in addition to and sometimes by the synagogues.

East Boston Ladies Auxiliary of Beth Israel, ca. 1911. Courtesy of the Jewish Cemetery Association of Massachusetts.

Many of the clubs were directed towards children and young people. The Ohel Jacob Junior was a club in East Boston that provided care and activities for children. An article in the Jewish Advocate from 1909 described how one local resident, Mrs. Shapiro, “devotes much of her time to care for the poor of East Boston and many families were saved the humiliation of applying to the charities through her efforts.” Among the many clubs were the East Boston Young Men’s Hebrew Association, the Jewish Welfare Center Club, Flowers of Zion, the East Boston Free Loan Association, East Boston Council of Jewish Women, the East Boston Ladies Auxiliary of Beth Israel, Chevra Ahawath Achoth (Sisterly Love Society) and Chevra Ahabath Achim (Brotherly Love Society).

The clubs arranged parties, educational opportunities, religious and cultural events and sometimes offered financial help. Many of the clubs organized concerts for fundraising purposes, and most held their meetings in Yiddish. Further, the clubs demonstrate how much of Jewish social life was structured around the different associations and how important it was for immigrants to have a sense of community and belonging. Equally important, these separate Jewish charitable organizations allowed Jews to seek aid within their own communities rather than from Protestant missionaries who sought to convert them to Christianity.

Newspapers such as the Jewish Advocate and the Jewish Times carried regular news about the East Boston community, publishing stories on the latest weddings, events, and politics in East Boston. Beginning in the mid-1920s, a journalist named Sydney Akell began writing monthly news about the East Boston clubs and community life.

Zionism and Politics

Zionism emerged around the beginning of the First World War and would have profound implications for American Jewry. Zionism had a significant role in the synagogues and Jewish community and contributed to how the Jews understood themselves in relation to the other immigrants and Americans. Besides the various Zionist clubs, the synagogues hosted events where rabbis advocated Zionism, and they kept the Jewish community informed about Zionist events and news in America and Europe. Through the synagogues the Jewish community in East Boston held charity events and raised money to help promote the Zionist movement. They supported the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine because they were familiar with the oppression faced by European Jews, including some of their own family and friends. Further, the large impact of Irish nationalism in Boston and the nativism that surged around the First World War sparked a desire for a Jewish homeland.

The rise of Zionism changed Jewish political behavior, and Jews began to run for political office. The older Jews tended not to participate in local politics because of language barriers, but they kept abreast of American political developments. The younger generations, however, were highly engaged in local politics in East Boston and debated important political questions and interests through various Jewish political organizations. East Boston Jews were also quick to defend their community from defamation, as was the case in 1916, when five prominent East Boston Jews challenged the Boston Planning Commission’s report that described the Jewish section as dirty, unattractive, and having a “depressive influence” on the community. They countered that Jewish families had improved the area, improving their homes, opening new businesses, and raising property values.

The Decline of Jewish East Boston

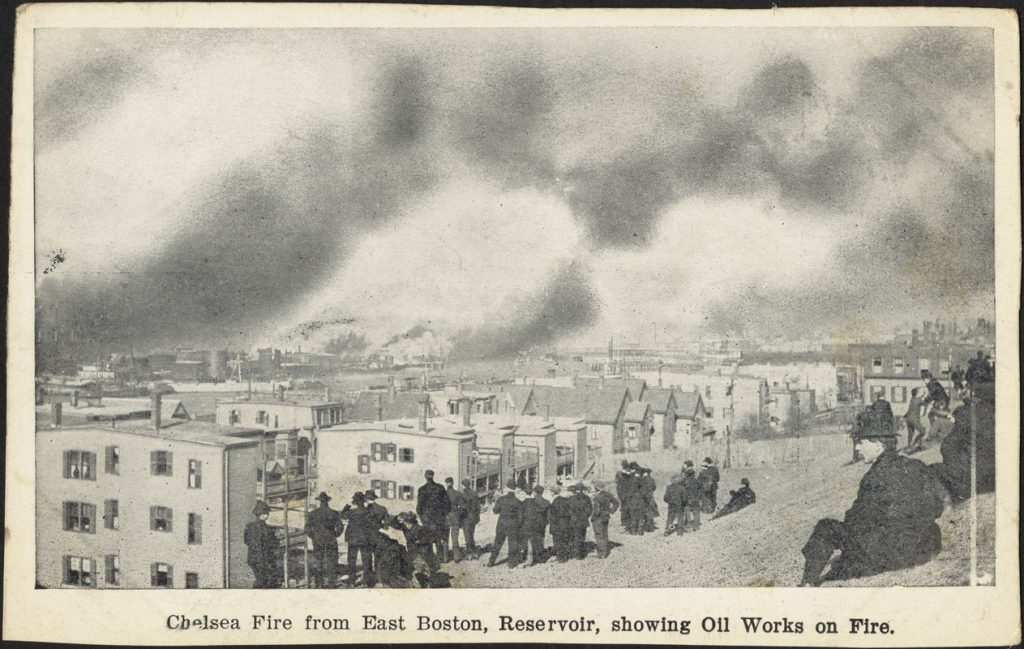

Postcard showing a view of the Chelsea fire of 1908, one of two fires that year that would spur Jewish outmigration from East Boston. Courtesy of Chelsea Public Library.

The Jewish community began to decline in East Boston in the years after the First World War. Even before the war, a massive fire on the East Boston waterfront in 1908 caused many Jews to relocate to Chelsea (which was rebuilding after its own fire the same year). Over the next twenty years, as Jews accessed better education and jobs, they continued to move out of the neighborhood, relocating to the northern suburbs as well as to Roxbury and Dorchester. The 1920 US Census shows a significant decline in the Russian population of East Boston, which continued in the following decades.

As Jews sought better living conditions in nearby suburbs, the East Boston synagogues and clubs lost members or closed. The Beth David synagogue, for example, was demolished in 1958. Ohel Jacob’s building was sold to the East Boston Health Center in 1970 and was then destroyed in a fire in 1973. Nevertheless, an aging and dwindling Jewish population remained in East Boston even after World War II and several Jewish-owned businesses continued to operate there through the 1960s. As the Jewish population declined, however, the Italian American population grew, marking yet another turning point in Eastie’s immigration history.

–Rebecca Solovej, Boston College

Works Cited

Boston 200 Neighborhood History Series. East Boston. Boston: Boston 200 Corporation, 1976.

Clingan, Carol. “Massachusetts Synagogues and Their Records, Past and Present.” Jewish Geneological Society of Greater Boston, 2010.

“Declares Jews Have Improved East Boston,” Boston Herald, August 18, 1916.

Kneeland, Paul. “Gutted Synagogue to Be Torn Down,” Boston Globe, February 25, 1973.

Sarna, Jonathan D., Ellen Smith, and Scott-Martin Kosofsky. The Jews of Boston. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005.

Mystic River Jewish Communities Project: East Boston. Jewish Cemetery Association of Massachusetts.

Resnek, Joshua. “Ralph Kaplan Led a Charmed Life.” Jewish Journal, March 17, 2016.

Woods, Robert A. and Albert J. Kennedy. The Zone of Emergence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1962, 187-219.

US, World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, Ancestry Library Edition.

US Census, 1910, 1920, 1930. Ancestry Library Edition.