Blue Hill Avenue along Franklin Park, 1932, the central artery of Jewish Dorchester. Courtesy of Boston City Archives.

Salem Street in the North End and Harrison Street in the South End are both remembered as the commercial hubs of old Jewish Boston. But in sheer size and population, nothing could compare to the Blue Hill Avenue district that anchored Dorchester’s Jewish community for much of the 20th century.

Jewish settlement in Dorchester began in the late 19th century, as new Jewish arrivals spread south from nearby Roxbury. Many came from the older downtown quarters, drawn by new streetcar lines and more spacious housing. At the heart of this settlement was Blue Hill Avenue, which connected Jewish residents from Elm Hill in Roxbury to Mattapan Square.

Agudath Israel synagogue building on Woodrow Avenue, 2003, now housing Temple Salem Seventh Day Adventist Church. Courtesy of the Dorchester Atheneum.

Among the most important neighborhood institutions were its synagogues, some which were newly organized and others that had relocated from the South and West Ends. By 1920 there were about 25 synagogues in Dorchester, including growing congregations such as Temple Beth El, Hadrath Israel, and Agudath Israel. By the early 1950s, there were more than 90,000 Jews within a three-mile swath of Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan—with Blue Hill Avenue as its central artery.

The Avenue was attractive for several reasons, including local streetcar lines which ran down the center, affordable triple-decker housing, and access to recreation in Franklin Park. When electric streetcar service was extended to Mattapan in the early 20th century, many triple deckers were built along Blue Hill Avenue and its side streets. Like other immigrants in Dorchester, Jewish families eagerly moved into these buildings and sometimes purchased them, typically renting out the other two floors to family or friends from back home.

Blue Hill Avenue and its side streets became a thriving commercial district during these years. Theodore White, who grew up in the neighborhood in the 1920s, remembered that, “Whatever you wanted you could buy on Erie Street… herrings were stacked in barrels outside the fish stores… all butcher shops were kosher… There were four grocery stores, several dry-goods stores, fruit and vegetable specialists, hardware stores.” Jewish peddlers were also a common sight, hawking their wares in Dorchester every Saturday night after the Sabbath ended. One popular entertainment venue was the Franklin Park Yiddish Theater on Blue Hill Avenue and Columbia Road. Live Yiddish plays were performed there from 1929 to 1936; it later became a movie theater.

In the video below, Jewish residents of Dorchester describe their experiences growing up in the area:

Over the course of the 20th century, the demographics in Dorchester changed substantially. As local resident Francis Russell described it, Jewish immigrants in the 1920s moved into a predominantly “Yankee-English” neighborhood. Several decades later, however, many of these native-born Protestant families had moved to the suburbs, along with their churches. In contrast, the Irish-dominated neighborhoods surrounding Blue Hill Avenue remained because parish communities were geographically rooted.

Dorchester’s original Jewish immigrants tended to be from more affluent backgrounds, but as these pioneers later moved to the suburbs, Blue Hill Avenue became a predominantly Jewish working-class neighborhood. As a growing African American population expanded across Roxbury, the Jewish area around Blue Hill Avenue became a kind of buffer between black neighborhoods in lower Roxbury and Irish-American neighborhoods in eastern Dorchester.

Throughout these transitions, Jews struggled to be fully accepted by their local community, especially by neighboring Irish-American families. The barriers between the two neighborhoods were vividly clear. Theodore White, a Jew who was born in Dorchester in 1915 and grew up to be a close advisor of President Kennedy, was the frequent target of Irish bullies walking around the city. “Within the boundaries of our community we were entirely safe and sheltered,” he explained, “but the boundaries were real. We were an enclave surrounded by Irish.”

These neighbors were frequently belligerent, and anti-Semitic violence peaked during the tension-filled years of the 1940s, when wartime propaganda and Catholic-Jewish tensions fueled a wave of assaults, vandalism, and attacks on synagogues. Instead of being passive victims, Jewish organizations and liberal groups joined forces to create the Good Neighbor Association of Dorchester, Mattapan, and Hyde Park in an effort to combat the violence.

Dorchester’s Jews also struggled against the Irish in the political realm. As citizenship rates grew, Jews were able to assert themselves politically as a sizeable voting body. In 1919, Polish immigrant Samuel Garfinkle, a Republican from Dorchester, was elected to the Massachusetts Senate, bolstered almost entirely by Jewish votes. In the decades that followed, Jews became a recognized political force in the city.

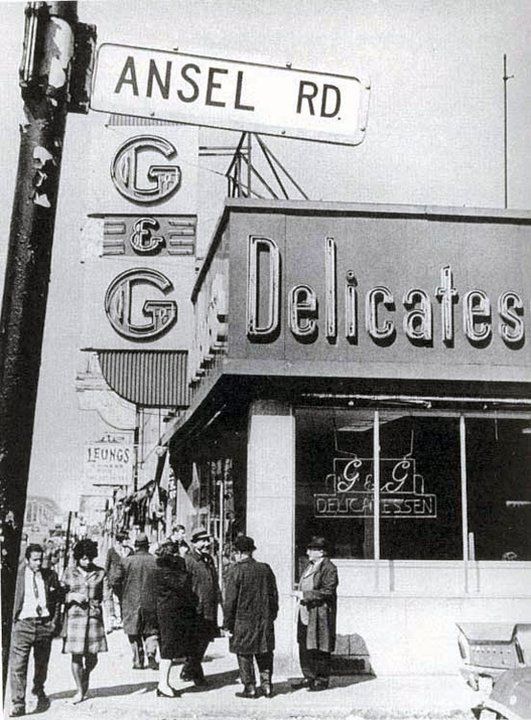

Located on Blue Hill Avenue, the G&G Deli served up corn beef with a side order of politics from 1948 to 1968.

After World War II, the G&G Deli opened in 1948 at the corner of Blue Hill Avenue and Ansel Road and quickly became the political epicenter of the Jewish community. As Hillel Levine and Lawrence Harmon noted, “the restaurant was positively electric on the eve of national and local elections.” Political debates constantly took place there, making it an important stop on the campaign trail.”

From the 1920s to the 1950s, one particularly important Jewish political figure was Samuel Levine, known in Dorchester as “the Chief.” Levine owned a funeral home on Washington Street (now in Brookline), and was well known for his local philanthropy. As Levine and Harmon explain, the Chief “got along famously with the Irish politicians citywide,” and used his funeral home every Saturday as a meeting point for “handpicked local candidates… to rub shoulders with elected and appointed officials from neighboring wards.”

While Dorchester’s Jewish population and political power peaked around World War II, the younger generation began moving to the suburbs. Many of their synagogues and businesses followed them to places like Brookline and Newton. From the 1960s to the 1980s, the Blue Hill Avenue corridor became home to black residents moving out from Roxbury as well as new immigrants from Haiti and the West Indies. But if you look closely, you can still find traces of Hebrew letters and Stars of David on some of the older buildings—evidence of the Avenue’s once vibrant Jewish life.

–Amanda Judah, Boston College ’20

Works Cited

Gamm, Gerald. Urban Exodus: Why the Jews Left Boston and the Catholics Stayed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Levine, Hillel, and Lawrence Harmon. The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press, 1993.

Norwood, Stephen H. “Marauding Youth and the Christian Front: Antisemitic Violence in Boston and New York During World War II.” American Jewish History 91, no. 2 (2003): 233-67.

Russell, Francis. The Great Interlude: Neglected Events and Persons from the First World War to the Depression. McGraw-Hill, 1964.

White, Theodore H. In Search of History: A Personal Adventure. New York: Warner Books, 1981.