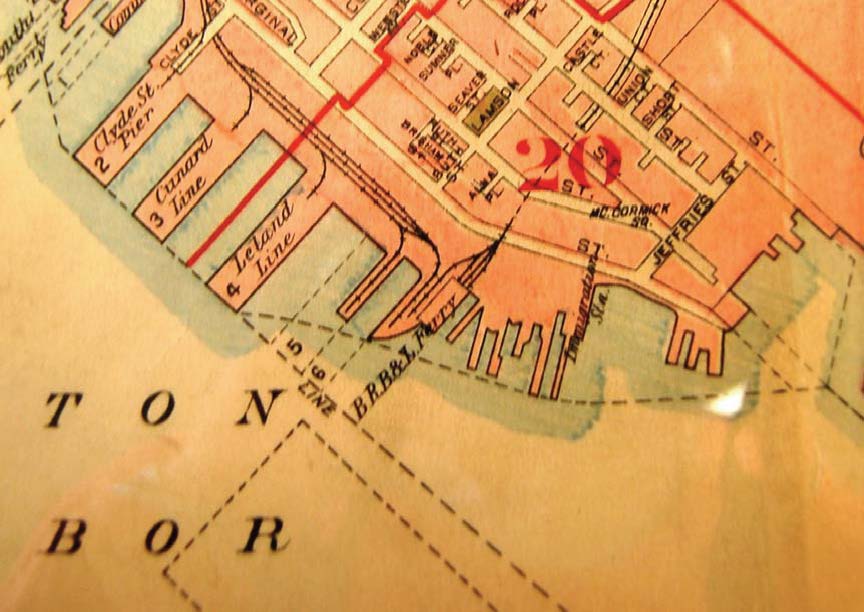

The East Boston Immigration Station, an immigration processing and detention center that was in operation from 1920 to the early 1950s. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library.

Record levels of immigration in the early twentieth century sparked a rising backlash against immigrants in the years before World War I. The newly revitalized Ku Klux Klan railed against immigrant Catholics and Jews, while elite groups like the Immigration Restriction League, headquartered in Boston, lobbied for federal legislation to curb immigration. Congress responded in 1917 with legislation requiring a literacy test for immigrants and creating an “Asiatic Barred Zone,” effectively outlawing nearly all immigration from Asia.

Even broader restrictions were enacted under the National Origins Act of 1924, which dramatically cut immigration levels through a new discriminatory quota system. Basing per-country quotas on the ancestry makeup of the US population, the new system favored older immigrant groups from England, Ireland, and Germany while tightly restricting visas for newer groups from southern and eastern Europe. Together, these new measures reduced the number of immigrants entering the country from more than 800,000 in 1921 to less than 150,000 by the end of the decade. In Boston, the foreign-born share of the city’s population shrank from 30 percent in 1930 to only 13 percent in 1970.

Declining immigration in the 1920s coincided with slowing economic growth in Massachusetts as some large textile manufacturers began relocating to the South. But it was the Great Depression that sent the Boston area into a deep and prolonged crisis as dozens of textile, shoe, garment, and other manufacturing industries collapsed. Immigrant workers faced staggering job losses and business failures; by 1934 roughly a quarter of the state’s workers were unemployed.

World War II revived Boston’s economy, at least temporarily. Federal defense contracts for shipbuilding, munitions, and other military goods got many factories humming again, employing thousands of immigrants and their children. After the war, special provisions to admit war brides and Jewish refugees from the Holocaust fueled a small uptick in immigration. With the onset of the Cold War, those fleeing Communism in Eastern Europe, China, and Cuba were also welcomed as refugees. Overall, however, Boston’s foreign-born population and labor force continued to age and decline. Native-born black southerners and Puerto Ricans who migrated to the city during these years helped pick up the slack at local manufacturing plants.

Immigrants arriving in the restriction era continued to cluster in many of the same ethnic neighborhoods, but they—and especially their children—experienced widespread upward mobility in the postwar period. For white immigrants and ethnics, US government-backed education and home loan programs under the GI bill offered new paths to white collar careers and homeownership in the burgeoning suburbs. Some families from China and the West Indies also saw economic gains in the postwar period, but persistent racial discrimination and segregation kept many confined to existing racial/ethnic enclaves. (Continue reading on the Global Era, 1965-Present)