Following the inauguration of President Donald Trump, efforts to establish sanctuary cities and campuses grew dramatically across the country. Several Massachusetts communities call themselves sanctuary cities, and others approved measures to limit their cooperation with federal immigration enforcement and promote themselves as welcoming places for the foreign born. Often seen as a new tactic in the fight against Trump’s immigration policies, the sanctuary movement has actually been around for more than thirty years, and the Boston-Cambridge area was a seedbed of these efforts from the beginning.

The sanctuary movement began in the early 1980s as churches and religious activists offered assistance and refuge to Central Americans fleeing civil wars and mass violence in El Salvador and Guatemala. With the Reagan administration supporting repressive military regimes in both countries, those fleeing violence were denied entry as refugees and many ended up crossing the border illegally. In 1982, a group of churches in Tuscon and San Francisco declared themselves sanctuaries for Central American refugees, sparking a movement that soon expanded across the country, including New England.

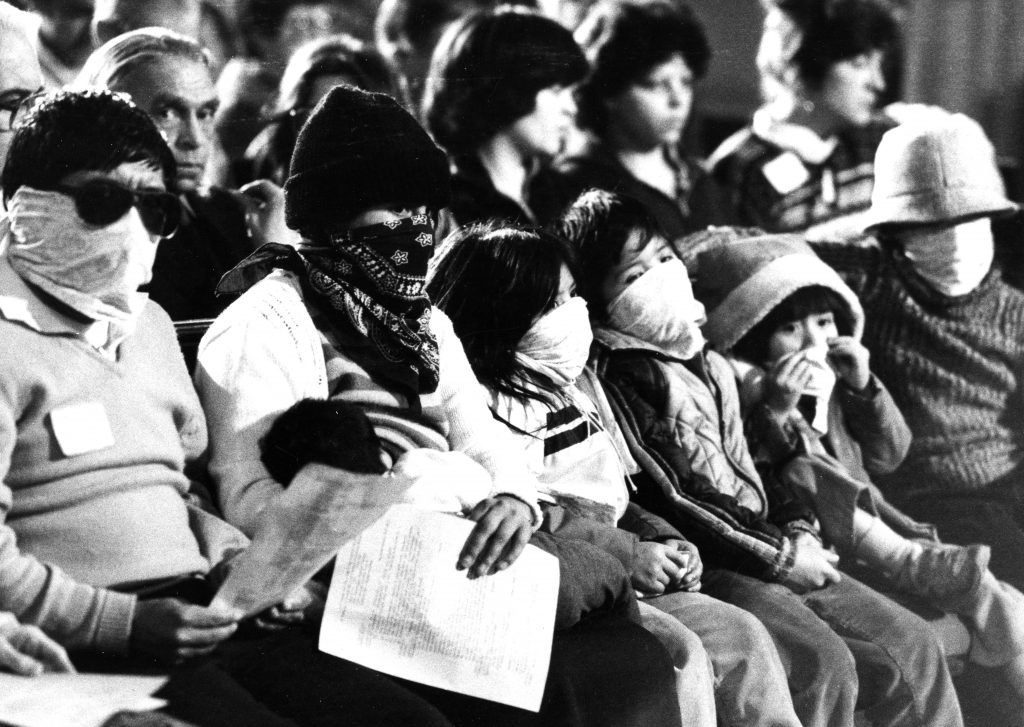

Cambridge became the local center of the movement, and in 1984 the Old Cambridge Baptist Church declared itself a sanctuary for those seeking asylum. Harboring a young Salvadoran woman who fled multiple rounds of torture by state authorities, church members held a two-week vigil with her and sponsored dozens of public forums where she and others gave testimony of their ordeal. The following year, local activists, working with the Cambridge Peace Commission, pressed the city council for a vote to make Cambridge a sanctuary city, meaning it would not cooperate with federal agents seeking to arrest and deport unauthorized migrants. It was the fourth such city in the country to do so, joining Berkeley, St. Paul, and Chicago.

During the 1980s, as Central Americans settled in Boston, Somerville, and Chelsea, these communities followed Cambridge’s lead. Somerville became a sanctuary city in 1987, and Boston and Chelsea did so over the last decade. Elsewhere in Massachusetts, Springfield, Holyoke, Amherst, Northampton, Orleans, and Lawrence all adopted sanctuary provisions as well. Some call themselves “sanctuary” towns or cities, while others have avoided the label but adopted similar public policies in hopes of encouraging immigrants’ cooperation with police and local government.

During the first week of his administration, President Trump targeted such communities with an executive order calling for the withholding of federal aid to sanctuary cities. Many of these communities in Massachusetts have defended their policies, and several others are now considering adopting sanctuary-like measures despite the punitive order. Whether these communities will lose federal funding remains to be seen, but legal challenges have already been filed. In early February 2017, Lawrence and Chelsea joined San Francisco in filing suit against Trump’s executive order. Shortly after, Newton declared itself a “Welcoming City,” and support for similar sanctuary measures are under consideration in Arlington, Acton, Salem, and Brookline. After thirty years, Massachusetts’ sanctuary movement appears to be experiencing a rebirth, and as in the 1980s, its growth has been a direct outgrowth of changing immigration policies on the federal level.