More than 400 immigrants take the oath of citizenship at a 2015 naturalization ceremony in Faneuil Hall. Michael Dwyer/AP

Piecemeal reforms in the immigration system after World War II eventually led to a massive overhaul under the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (also known as the Hart-Celler Act). Part of the raft of civil rights legislation passed in the 1960s, the 1965 act eliminated the old discriminatory quotas of the 1920s and raised the annual ceiling on immigration, allowing new arrivals from across the globe. Equally important was the act’s expansion of preferences and exemptions for the highly skilled and for family members of naturalized citizens. The latter provision created a parallel stream of non-quota family immigration, while skill preferences led to a new influx of foreign-born scientists and professionals.

At the same time, the global conflicts of the Cold War produced a string of refugee crises in places like South East Asia and Central America. US support for anti-Soviet dictatorships in the Caribbean and Latin America also prompted others to flee repression in their homelands. After the Cold War ended, violent struggles in the Balkans, Africa, and the Middle East led to new refugee migrations. More generally, the acceleration of globalization since the 1990s led to free trade agreements and other global financial policies that deepened hardships in developing countries. Skyrocketing inflation, unemployment, and poverty soon sent many abroad. As national quotas were quickly filled, a growing number came without authorization.

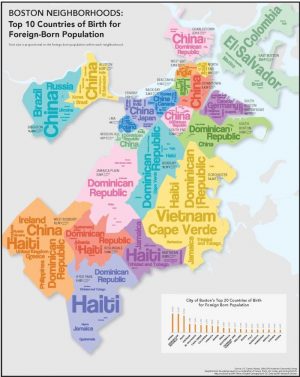

In greater Boston, recent immigrants have come from a strikingly diverse array of countries, mainly in Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean. China, Haiti and the Dominican Republic have long been the top countries of origin, but sizeable groups also hail from Brazil, India, Vietnam, El Salvador, and Guatemala. The diversity lottery, a provision of the 1990 immigration act that offers visas to those from underrepresented countries, has also increased the number of African arrivals.

Newcomers in the 1960s and 1970s settled in Boston’s older immigrant quarters in Chinatown and the South End, as well as older industrial communities in East Cambridge, Lynn, and Chelsea. In the 1980s, however, urban redevelopment and gentrification drove up housing prices in central Boston, pushing many newcomers to outlying neighborhoods such as East Boston, Dorchester, and Jamaica Plain.

By the nineties, many immigrant families were heading to the suburbs, creating new multiethnic populations in Quincy, Malden, Somerville, Framingham, and many other communities. Today, there are more foreign-born residents in the metro area suburbs than in the city of Boston itself.

Unlike earlier immigrants who were mainly unskilled factory workers and laborers, recent arrivals include a large contingent of doctors, engineers, scientists, and other highly skilled workers. They have helped build Boston’s new knowledge economy, which has eclipsed the region’s older manufacturing sector. Other immigrants also play vital roles in the region’s lower-paid service industries, including food service, building maintenance, healthcare, and childcare. Often staffed by immigrant women, the care industries have grown markedly as more middle-class women have entered the labor force since the 1970s. For immigrant men, construction and manufacturing continue to be important, although the latter has been in decline as more and more manufacturing jobs have moved abroad.