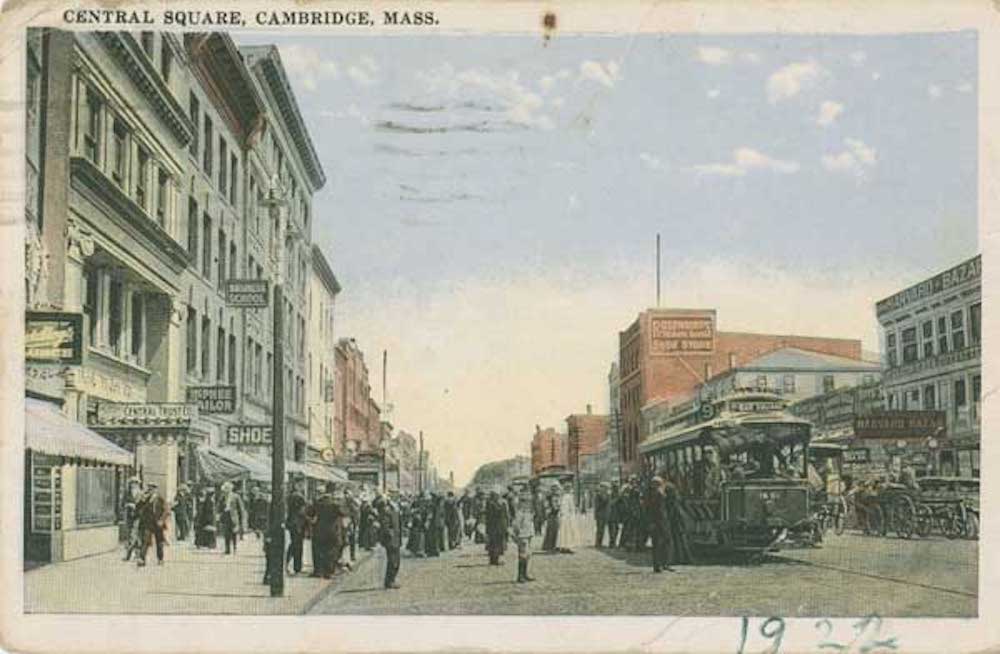

Central Square became Cambridge’s largest commercial center in the early 20th century, serving growing immigrant communities from Ireland, Canada, Portugal, and the West Indies. After World War II, the Square and an adjoining area known as “the Port” would become the center of Cambridge’s Latin American communities.

When the Puritans arrived at the Shawmut peninsula in 1630, a smaller group continued upriver to found the village of Newe Towne, renamed Cambridge in 1638. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the densest settlement surrounded the Cambridge Common and Harvard College, founded in 1636. When this settlement—known as Old Cambridge—joined with Cambridgeport, East Cambridge, and North Cambridge to form the city of Cambridge in 1846, each neighborhood had developed a distinct identity and demographic makeup. Immigrants were a big part of that history, and they have continued to shape life in Cambridge up to the present day.

Cambridgeport

During the late nineteenth century, the civic and commercial center of Cambridge shifted from Harvard Square to Central Square, the downtown area of Cambridgeport. The population of this area first spiked with the opening of the West Boston Bridge in 1793, giving Cambridgeport direct access to Boston and its flow of people and goods. Manufacturers produced musical instruments, rubber, soap, and candy. The confectionary industry in particular flourished, and by the 1930s and 1940s, there were 25 or more candy companies in Cambridge, mostly in Cambridgeport. Initially skilled laborers and mechanics from Germany, Labrador, Nova Scotia, and the British Isles manned these factories, but they were later replaced by Irish immigrants arriving in the second half of the nineteenth century. The offspring of these foreign-born workers replaced the descendants of the Puritans as the area’s commercial and civic leaders by the turn of the twentieth century.

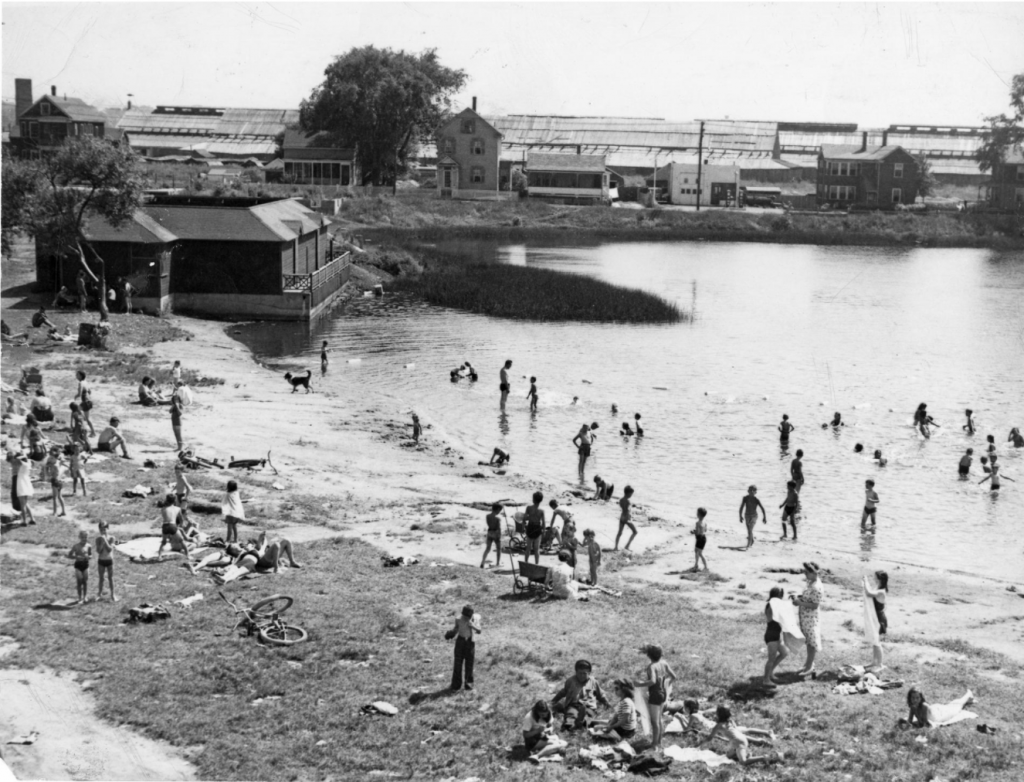

Other migrant groups also flocked to Cambridgeport, which consistently housed and employed half of the city’s total population. After the Civil War, the black community tripled in size, growing to at least 1500 in 1910. About half migrated from the South as part of the Great Migration, while others came from Nova Scotia and the West Indies. Swedish migrants began settling in Cambridgeport after 1890, and Portuguese immigrants arrived after 1895. Refugees from the Russian Empire—including Poles, Latvians, Lithuanians, and Jews—arrived around the same time. The number of Greek, Syrian, and Armenian immigrants also expanded during these years. Between 1900 and 1925, Barbadians of African descent fleeing colonialism moved to the Coast—today’s Riverside neighborhood—and to the Port.

In 1953, the Cambridge Planning Board divided the city into districts, separating Cambridgeport into two zones north and south of Massachusetts Avenue. The northern zone, known as the Port, became Area 4 (in 2015, it officially reverted back to the Port). During the 1960s and 1970s, Puerto Rican and Dominican migration expanded the center of the Latino population from Cambridgeport into the Port around Columbia Street. The first Puerto Rican arrivals worked as migrant farm hands around Boston, while others found manufacturing jobs despite deindustrialization.

Dominicans, who fled tumultuous conditions in the Dominican Republic following the assassination of the dictator Rafael Trujillo, found that the Port contained several affordable housing options and empty apartments due to suburbanization. Columbia Terrace, a multifamily apartment building purchased by the Cambridge Alliance of Spanish Tenants, offered large rooms around a central courtyard. Nearby, the government housing projects Newtowne Court and Washington Elms accommodated Latino immigrants through subsidized rents. By 1990, the Port was the most racially diverse neighborhood in Cambridge, as well as the most underfunded. Beginning in the 1990s and 2000s, the area saw new waves of arrivals from the West Indies, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Haiti, Central America, South America, eastern Europe, Laos, and Vietnam. The Port remains one of the most diverse communities in Cambridge.

East Cambridge

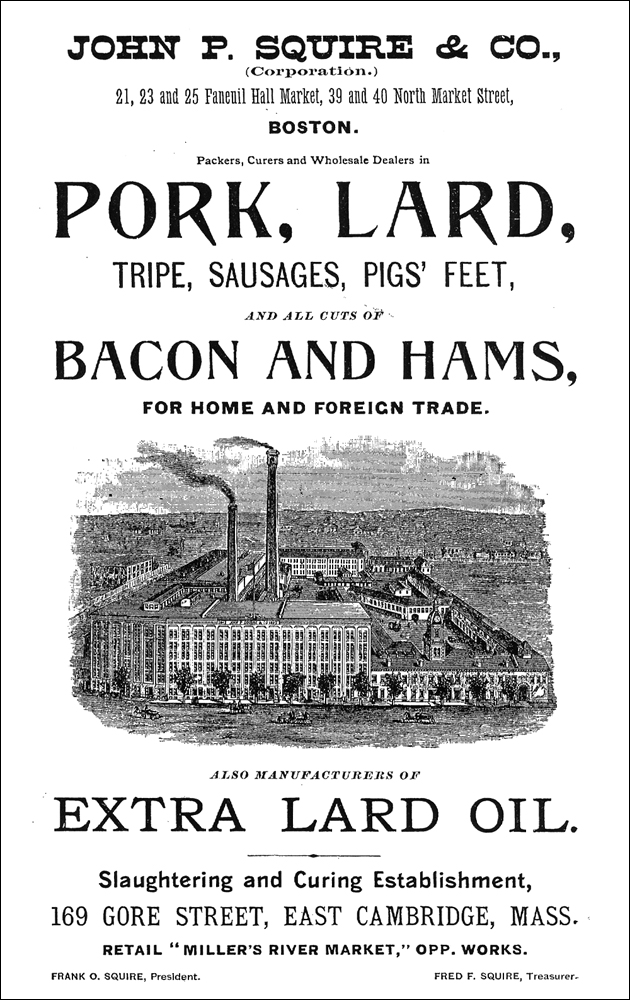

East Cambridge, the city’s other historic center of industry, has also housed a substantial population of foreign born. Connected to Boston by the Canal Bridge in 1809, East Cambridge was an industrial hub throughout the nineteenth century. Glass-making was the top industry at mid-century, but it was later supplanted by woodworking, meatpacking, and metalworking plants that drew on a growing Irish immigrant workforce. John P. Squire’s slaughterhouse and meatpacking plant was the largest employer in the area in 1880, when nearly 80 percent of East Cantabrigians had two foreign-born parents. Furniture, organ, and coffin factories crowded the cityscape as well. Several of these factories offered noontime English classes, and the East End Union settlement (now East End House) opened in 1887 to serve the broader immigrant community.

In the early twentieth century, the city filled in the tidal flats south of Charles Street. Heavy industries, requiring direct railroad connections for raw materials and finished goods, moved into the area. Italians, Poles, and Portuguese settled in East Cambridge as the Irish left for other parts of Cambridge and the suburbs. These groups moved into East Cambridge from the densest, poorest ethnic enclaves of Boston that were just across the Charles River. Italians and Portuguese, originally from the Azores, relocated from the North End, and Poles moved there from the West End. By 1920, Russian Jews, Lithuanians, Albanians, Syrians, and Armenians all found new homes in East Cambridge. Although local industries suffered during the Great Depression, the neighborhood rebounded during and after World War II, and more West Enders arrived following the razing of that neighborhood in the late 1950s. Not long thereafter, a new wave of Portuguese immigrants, fleeing the authoritarian Estado Novo government and volcanic eruptions and earthquakes in the Azores, joined the Portuguese community, as did Portuguese-speaking immigrants from Brazil. Through the 1980s, these multiple ethnic groups aided in reinvigorating a deindustrialized East Cambridge.

North Cambridge

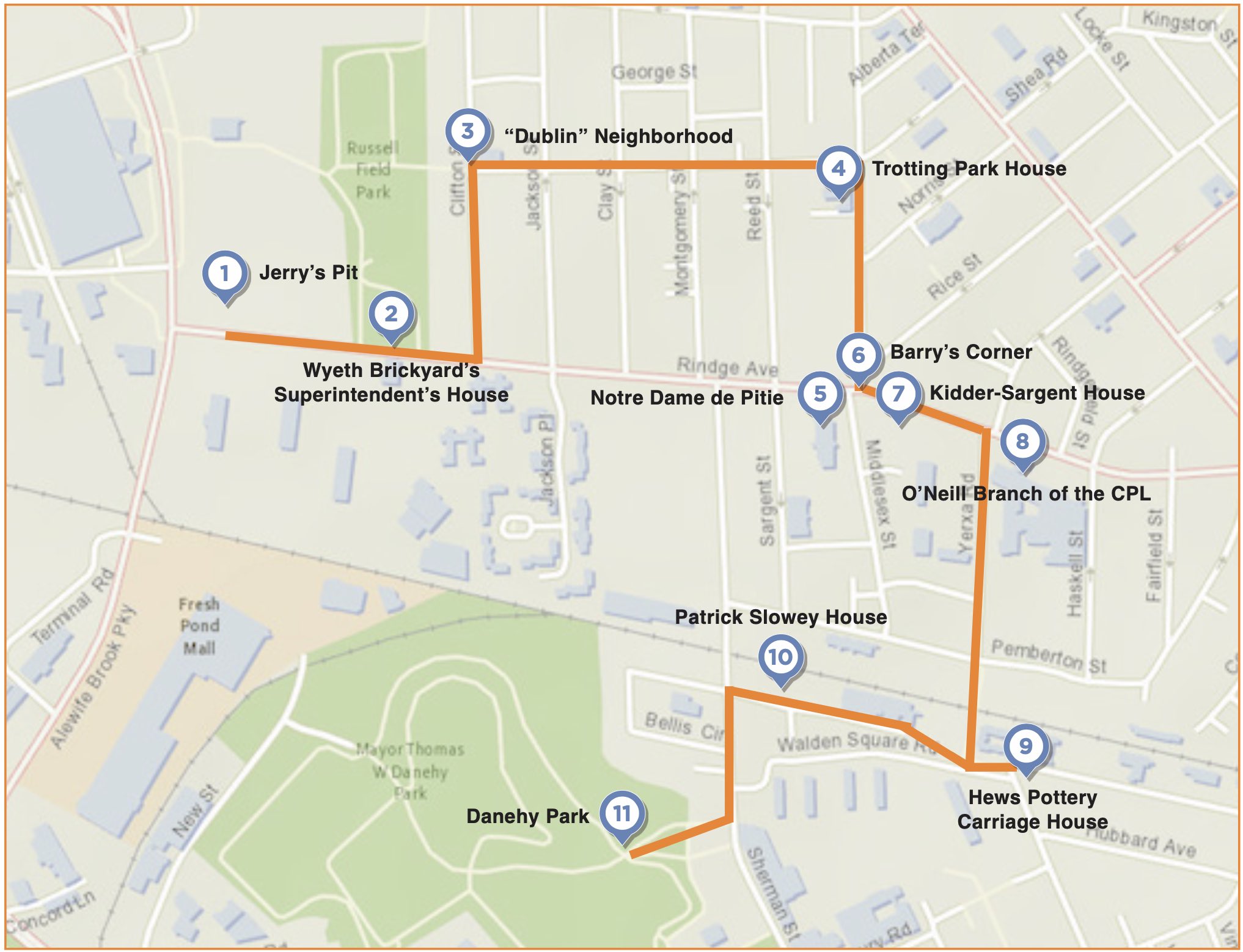

While more homogenous than Cambridgeport and East Cambridge, North Cambridge and the Old Cambridge historic district have similarly been shaped by the foreign born. Beginning in the 1840s, Irish immigrants found employment in the cattle and brickmaking industries of North Cambridge. Workers unloaded cattle at the Fitchburg Railroad, where they would pass through the Walden Street Cattle Pass tunnel in route to the Cambridge Cattle Market and, after it closed in the 1870s, to the Brighton Abattoir. Irish and French Canadian workers also found jobs in the clay pits and brickyards which sprung up around the area’s rich clay deposits.

The brickyards employed generations of immigrant workers, including the family of legendary speaker of the US House of Representatives, Thomas “Tip” O’Neill. A few blocks away from the “Dublin” neighborhood where O’Neill grew up was the “Little France” community of Canadian families. One resident, Francis Xavier Masse, established FX Masse Hardware Company at the corner of Sherman and Walden streets in 1888. The iconic store served the community for 125 years before closing in 2013.

Newer immigrant groups gravitated toward the institutions of the old ones: when Haitian immigrants started arriving in North Cambridge in the 1970s, they were drawn to Our Lady of Pity, a French Canadian church. It “offered a welcoming embrace in a familiar language,” as the Boston Globe reported. In 2003, the church closed after many members of its dwindling group of Haitian churchgoers moved away because of rising housing costs.

Old Cambridge

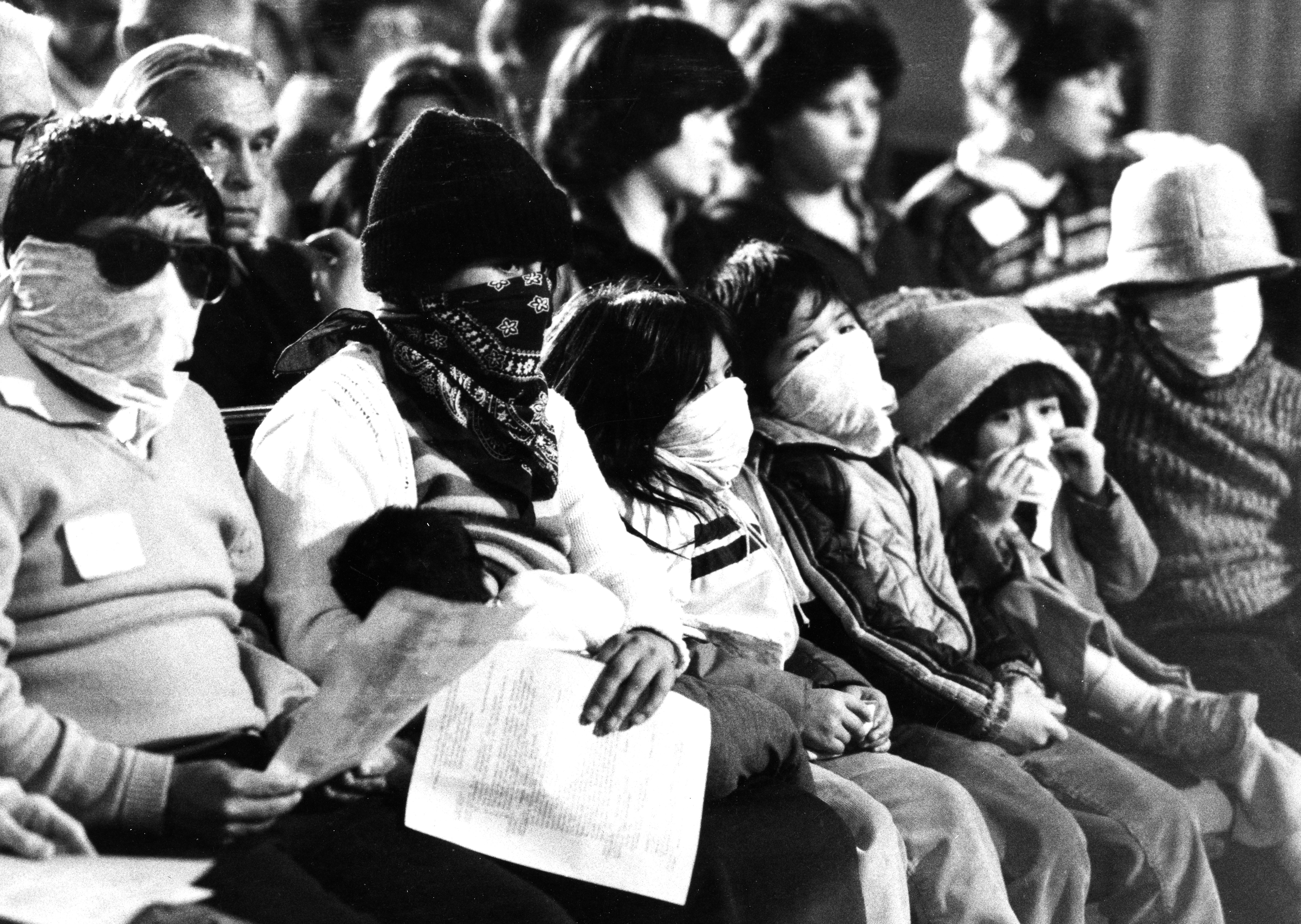

Old Cambridge, long the stomping ground of Harvard students, professors, and the Yankee elite, became a haven for immigrants in the 1980s. The Old Cambridge Baptist Church was at the center of the asylum movement, welcoming refugees from war-torn El Salvador and Guatemala. Centro Presente, a refugee assistance organization, worked with local local residents to have Cambridge designated a sanctuary city, and the city later granted voting rights to resident noncitizens. Additionally, Harvard professors founded the Cambridge Buddhist Association in 1957, the first Buddhist organization in the greater Boston area. It would welcome arrivals from Tibet, Sri Lanka, and other parts of East and Southeast Asia. In the 2000s, Korean, Tibetan, and Thai immigrants founded their own Buddhist temples in Cambridge.

Skilled migrants were first attracted to Cambridge’s tech industry during the Cold War. Surrounding the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the tech boom escalated real estate development and pushed many foreign-born Cantabrigians out of the Port and East Cambridge, where the tech industry replaced earlier manufacturing jobs and promoted gentrification. At the same time, however, universities like Harvard and MIT—and the tech and biotech firms that have sprung up around them—have attracted new highly skilled immigrants, mainly from Asia. In 2017, the top foreign-born groups living in Cambridge were from China, India, Korea, Ethiopia, Haiti, and Canada. Though the percentage of foreign-born in Cambridge fell from its peak of 33 percent in 1910 to 15 percent in 1970, it rebounded to 27 percent in 2010 and has remained roughly at that level since.

–Madeline Webster

Works Cited

Boyer, Sarah. All in the Same Boat: Twentieth-Century Stories of East Cambridge. Cambridge: Cambridge Historical Commission, 2005.

Boyer, Sarah. In Our Own Words, Stories of North Cambridge, 1900-1960. Cambridge: Cambridge Historical Commission, 1997.

Boyer, Sarah. Crossroads: Stories of Central Square, 1912-2000. Cambridge: Cambridge Historical Commission, 2000.

Boyer, Sarah. We Are the Port: Stories of Place, Perseverance, and Pride in the Port/Area 4, 1845-2005. Cambridge Historical Commission, 2015.

Hernandez, Deborah Pacini. “Quiet Crisis: A Community History of Latinos in Cambridge, Massachusetts.” In Latinos in New England, edited by Andrés Torres. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006.

Johnson, Marilynn S. The New Bostonians: How Immigrants Have Transformed the Metro Area Since the 1960s. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015.

“WGBH Journal; The Portuguese Community in Cambridge and Somerville, Interview with Victor Sidel, and News of the Day with Louis Lyons ,” 1978-03-24, WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC.