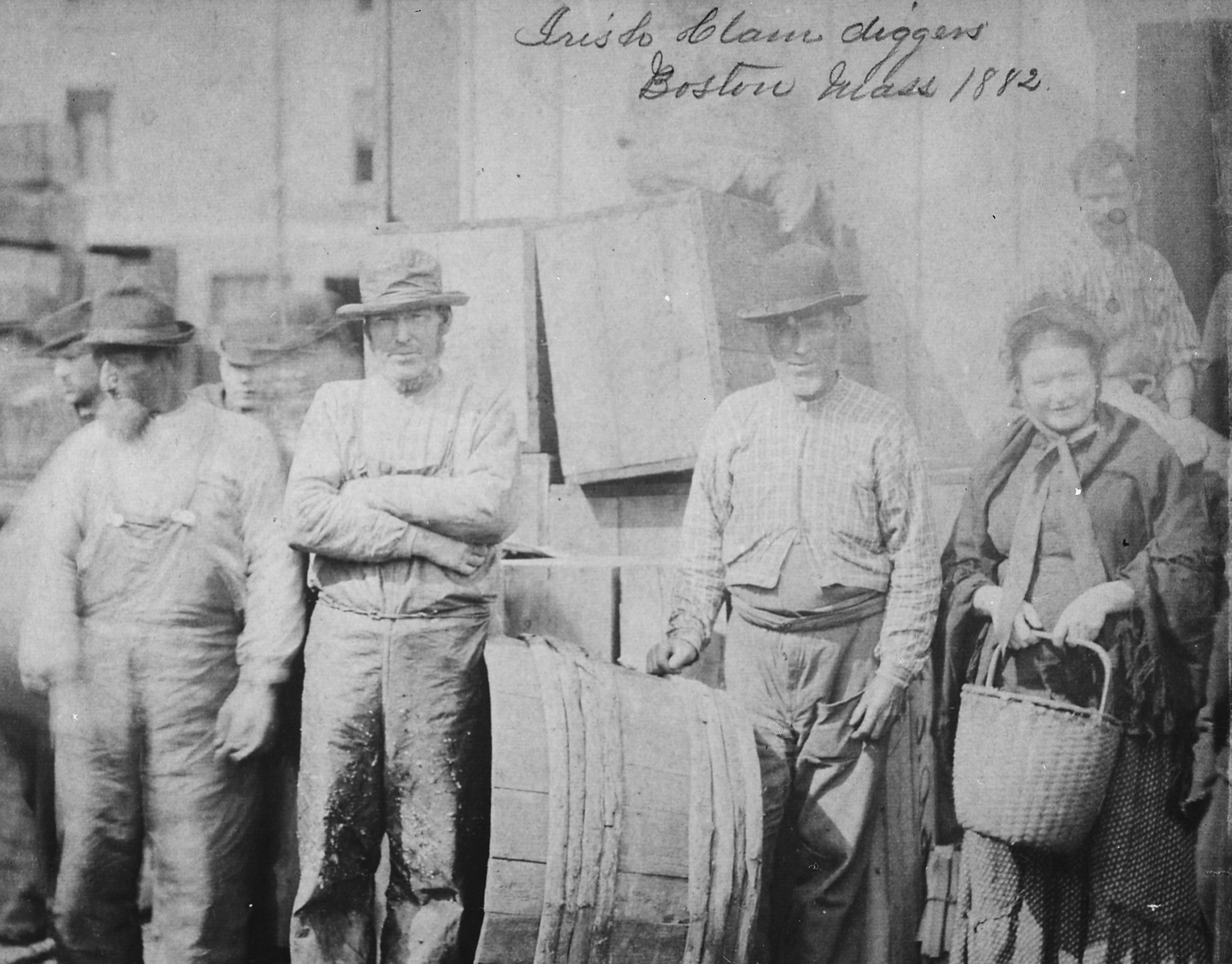

Irish clam diggers on a wharf in Boston, 1882. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Irish immigration to Boston began in the colonial period with the arrival of predominantly Protestant migrants from Ulster. Many of these early Irish arrivals worked as indentured servants to pay for their passage, typically earning their freedom after seven years. The Scots-Irish, as they were later called, emigrated in much smaller numbers than the next wave of Irish Catholic immigrants who began arriving in the 1820s.

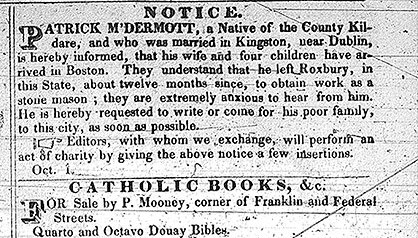

Since the seventeenth century, English rule in Ireland had created a society in which the vast majority of Irish people lived in poverty as tenant farmers. From 1846-1852, a blight that devastated the potato crop led to a great famine, resulting in widespread starvation, disease, and deaths. Seeking refuge and opportunity, thousands of Irish began to migrate to urban centers in the British Isles and abroad, including Boston. Coming especially from the southwestern counties of Cork, Galway, Kerry and Clare, the new Boston arrivals were predominantly Catholic and produced a marked demographic shift in a historically Protestant city. With the exception of the Civil War years, Irish immigration to Boston continued throughout the nineteenth century, as conditions in Ireland remained grim. The foreign-born Irish population of the city reached its numeric peak around 1890.

Following some eighty years of relative decline, Irish immigration to Boston once again grew in the 1970s and 1980s as the Irish economy faltered. The demand for visas, however, outpaced the quota established under the 1965 Immigration Act, and many thus came without authorization. Some were able to adjust their status under the diversity lottery established in 1990 in response to organized efforts by the Irish Immigrant Reform Movement. Many others, however, returned to Ireland as the so-called “Celtic Tiger”—Ireland’s economic boom of the 1990s and early 2000s—improved prospects back home.

Patterns of Settlement

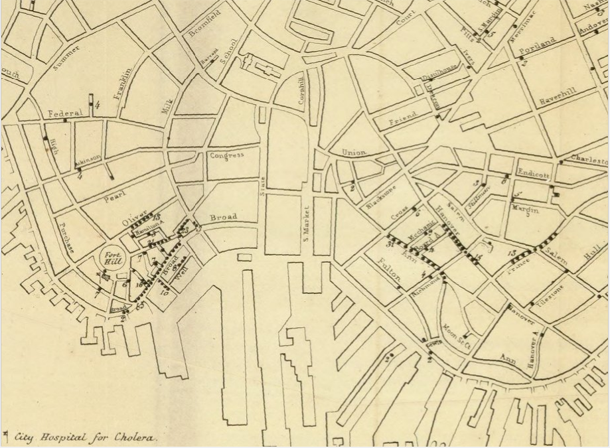

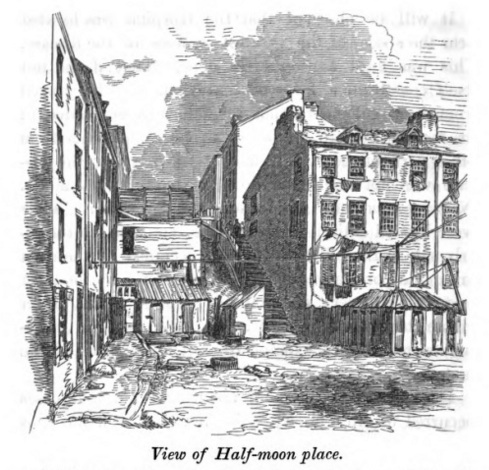

Early Irish immigrants settled in Boston’s North End and Fort Hill (the presentday financial district) neighborhoods. With the creation of new land in the West End and South Cove in the mid-nineteenth century, the Irish became the first of many immigrant groups to settle in these areas. Soon after, the Irish were also moving into South Boston and Charlestown, which would become and remain predominantly Irish-American neighborhoods for most of the twentieth century. Others settled in parts of Dorchester, Roxbury, East Boston, Cambridge, and other nearby towns, where new Catholic parishes anchored emerging ethnic neighborhoods. Many of these immigrants’ children and grandchildren moved to the suburbs after World War II, with the highest concentrations located on the South Shore.

Workforce Participation

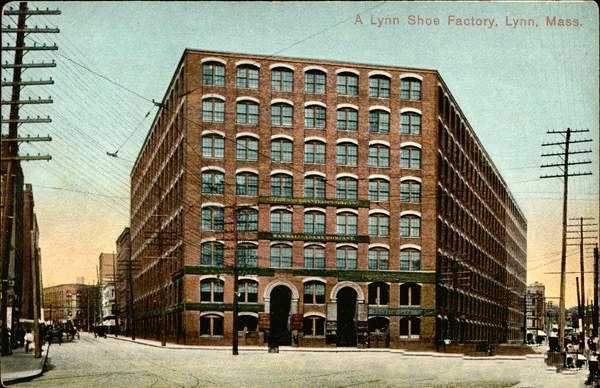

Coming mainly from impoverished agricultural areas, most Irish immigrants initially worked as unskilled laborers, dockworkers, hod carriers, teamsters, and domestic servants. Much of the City of Boston, in fact, was built with Irish labor, quite literally in the case of the South Cove and Back Bay, tidal basins that developers and their immigrant workers transformed into fashionable residential neighborhoods in the 1840s and 1850s. Irish men also provided labor for building local canals, railroads, aqueducts, and the Boston subway system. Irish women made up the majority of the city’s domestic servants, as well as laboring alongside Irish men and children in the region’s factories and sweatshops. As they attained higher levels of education and social acceptance, Irish women moved into teaching, retail, and clerical work, while Irish men worked as police officers, firefighters, and civil servants. By the middle of the twentieth century, the Boston Irish were well established as political and business leaders, a trend highlighted by the election of President John F. Kennedy in 1960.