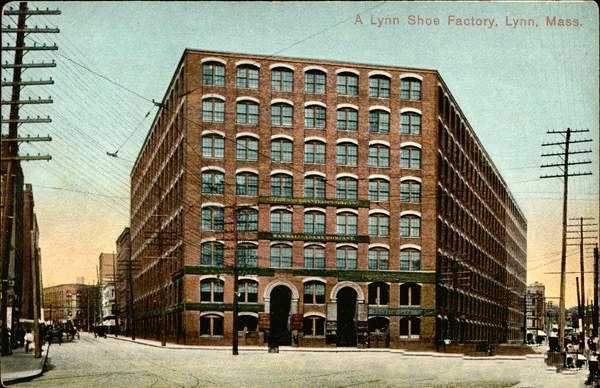

The following account is one of the earliest oral histories with an immigrant shoeworker in Lynn. The interviewee, who is unnamed, was born in 1859 and came to the US in 1866. He was interviewed in 1938 by Jane K. Seary, a field worker with the Federal Writers Project, a New Deal agency that collected personal narratives of American workers. Entering the shoe industry in the 1870s, the man describes his trip to America, working in the shoe factories, labor strife, and the changing composition of the Lynn workforce. When he gave this interview, he was retired from the local shoe industry, which had by then been in decline for more than a decade.

I was born in Ireland, in County Cork, just a year before the Civil War began in America. My father came to America before I was born for there wasn’t much work in Ireland on account of the bad results of the potato crop failing some years before. There wasn’t much work in America either though, for there was war talk and that made business bad. I guess he must have been homesick too for he came back home, but he died when I was thirteen months.

When I was born, that made six of us children. When my oldest brother and sister got up in their teens though, they came to America and went to Lynn to live with my father’s sister. They work in the shoe shops.

They was making shoes for southern [slaves*] then. They was rough things. They wasn’t even put together in pairs. The right was just like the left. Instead of being packed like today, they was just tied together with a string and dumped together in big boxes.

I was seven years old when my mother brought the rest of us that wasn’t here, over to America. We got on a steamboat at Cork and thought we’d get to Boston in about ten days. But half way across, the boat broke down and we had to get towed back to Cork. We all lived on the boat in dry dock there for about a week while they was getting it fixed. This time we come straight to New York for there was no time to stop at Boston….

It was in a vacation time, about five years after I come to Lynn, that I first started to work in the shop. We was living in a house belonging to Mr. Phelan—he was Irish, an a smart one, too, for he had got up to the place where he owned some houses and he run a shoe shop. I was out in the yard whittling at some wood for I didn’t have much to do with my time in them days. “Want to put that boy to work?” Mr. Phelan asked my mother.

He took me right into the cutting room. In my day that was the white collar room in the shop, for often the boss’s son and his relatives worked there. We used to go in through the front door, not the back door like all the other help. And the other workers was always jealous of the cutters….

When I went into the cutting room, I started at the beginning. First I learned how to dink out pieces of waste leather for the trimmings. To dink out leather, you have a piece of cast iron or steel shaped like the pattern you want to make. You put this on the leather like you put a cookie cutter on dough. You pound it then with a hammer.

I did the best work I could for I wanted be a journeyman cutter. The usual time to get to be that was three years. So I made a bargain to work for a low pay during that time so I could learn. It was sort of like you was under contract. I was going to keep my bargain all right but they didn’t keep theirs. There come a slack time and the boss said to me, “Sorry Jackie, but I guess you’ll have to lay off for two three weeks…. I was sore. I wasn’t a journeyman and wouldn’t be for another three quarters years, so I couldn’t expect to get a journeyman’s job in another shop. But I thought I’d try. And by dang, I got that job and the pay that went with it….

During the 60 years I been in the Lynn shops, I guess I worked in more than 40 shops. I was never out of work much. The seasons sort of joined together in them days, and if a fella kept on his toes he could most always work all the year round….

I remember once though, during the 80s, how it was a lot like it is today, though not so long. Most of the shops had ‘No help wanted’ on their doors. That’s an awful sign for a worker to read, ‘No help wanted.’

After that time (the 1880s), that is after the strikes about that time, the foreigners started to get into the shops. I was never one to say they was a bad lot, but a lot of the fellas in the shop hated them. You see we was getting good pay and they’d work for less money. It made it bad for all of us….

The strikes brought in a lot of folks from the provinces —Canada—and a lot from down Maine. Later the Greeks come, and the Italians, the Germans, the Polish and a lot of others. When I first went in, there was just Yankees and Irish and Irish-Americans. Today the shops has all kinds of people working in them.

But they got in the shops just the same and every year more and more squeezed in, starting at the jobs the rest of us didn’t want and working themselves up. There wasn’t many that got in the cutting room though, and they didn’t get in the welters** union for a good while.

It was a good while later before the Jews got in. That was in the 1900s. Most always they started in the junk business and after a while they picked up scrap leather and sold it. They got in the business that way and after a while started their own shops.

*The informant used a racial epithet here to describe enslaved African Americans.

**Welters were workers who attached the outersole to the rest of the shoe.

From: Searcy, Jane K. Sixty Years is a Long Time. Massachusetts, -39, 1938. Manuscript/Mixed Material.