Chinese funeral on Harrison Street in Chinatown, ca. 1890. Courtesy of the Trustees of Boston Public Library.

Large-scale emigration from China to the US began in the 1850s as overpopulation, land shortages, colonial warfare, and recurring famines ravaged Guangdong and other southern provinces. Going first to California, Chinese immigrants began settling in Massachusetts in the 1870s after a North Adams manufacturer recruited them during a shoemakers strike. Before long, some moved to new work sites in Worcester and Boston. By 1900, the Census counted more than a thousand Chinese in Boston, the majority from the Taishan region of Guangdong. With the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and other restrictive measures, however, Chinese immigration was reduced. Although a small number of elite immigrants and “paper sons” (those with falsified documents) arrived thereafter, the Boston Chinese community remained heavily male and grew increasingly older.

During the World War II years, the repeal of Chinese exclusion and the passage of the War Brides Acts in 1945 and 1946 allowed a small infusion of new Chinese immigrants, most notably war brides who married Asian American GIs. In the ensuing Cold War, recruitment of Chinese science and engineering students to local universities brought several hundred more new residents, many of whom sought refuge in the US after the Chinese revolution of 1949. Subsequent communist restrictions on emigration, however, meant that until the 1980s most Chinese immigrants would come from the Republic of China in Taiwan and the British colony of Hong Kong.

Once US diplomatic relations with the Peoples Republic of China improved, a growing number of students and immigrants from the mainland began arriving in the 1980s. These newcomers came from across the country and soon outnumbered those from Hong Kong and Taiwan. Many spoke Mandarin as well as their local dialects, in contrast to the older settlers who spoke mainly Cantonese and Taishanese. Making use of the skill preferences and family reunification exemptions of the 1965 Immigration Act, the Chinese have become one of the largest foreign-born groups in the city and state.

Settlement Patterns

The earliest Chinese arrivals pitched their tents along Oliver Place (now known as Ping On Alley) in what would soon become Chinatown. Chinese occupancy spread to adjoining blocks as far south as Kneeland Street and later spread further south as neighboring Syrian and Irish immigrants moved out. Although the pre-World War II Chinese population remained heavily concentrated in Chinatown—the nation’s third largest at the time—there were also small pockets of settlement in Cambridge, Lynn, and other nearby towns. These communities grew after World War II as a small but growing number of Chinese and Chinese American families relocated to the suburbs.

After World War II and especially after 1965, growing Chinese immigration and urban renewal brought extraordinary land pressures on Chinatown. In the 1960s alone, the construction of the Massachusetts Turnpike Extension, the Southeast Expressway, and the Tufts Medical complex reduced Chinatown’s land base by half while its population grew by 25 percent. Although many residents fought against unbridled development, thousands of Chinatown dwellers decamped for other neighborhoods such as the South End, Mission Hill, and Allston-Brighton. Other working and middle class families settled in nearby suburbs such as Malden and Quincy. In fact, the latter became so popular with newcomers that by 2000 its Asian American population was more than triple that of Chinatown’s. In addition, Chinese American professionals have taken up residence in affluent suburbs across the metro area, including Brookline, Newton, Arlington, Lexington, Burlington, and Acton.

Workforce Participation

Some of Boston’s earliest Chinese settlers were laborers hired to build the Pearl Telephone Exchange downtown or to work in the railroad yards around what is now South Station. By the early 20th century, though, most Chinese immigrants were employed in a growing enclave economy made up of hand laundries, restaurants, and other Chinese-owned businesses. In fact, the US Census of 1900 indicated that 88 percent of Chinese workers labored in laundries, mostly small one or two-man operations scattered across the metro area.

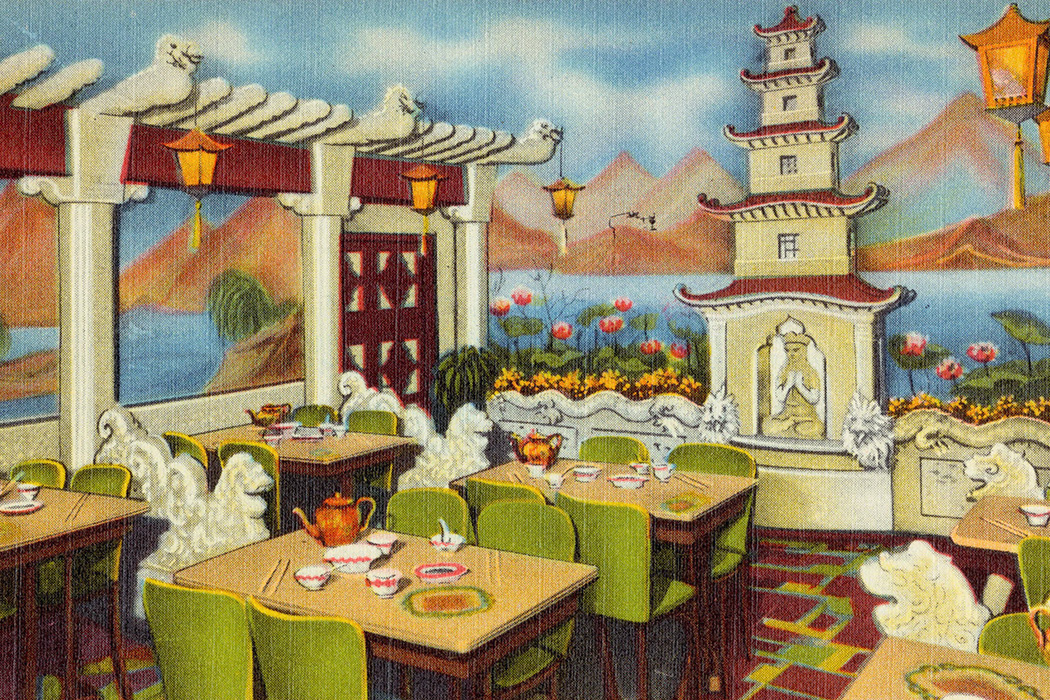

Other immigrants found work as cooks, servers, and dishwashers in a growing network of Chinese restaurants that became popular with a broader American clientele after World War I. By the mid-twentieth century, many family-owned Chinese restaurants employed numerous male migrants, while Chinese women often took up sewing work in the city’s garment industry. With the closing of these shops in the 1970s and 1980s, many of the women shifted into the service sector.

At the same time, a growing stream of Chinese students and educated professional workers entered the country after 1965. Graduating from local universities, or recruited for their professional and technical expertise, Chinese immigrants have been vital contributors in the sciences, engineering, medicine, and information technology. Some have gone on to launch their own businesses in software development, biotechnology, electronics, and other industries.