Following the inauguration of President Donald Trump in 2017, efforts to establish safe communities for immigrants grew dramatically across the country. Several Massachusetts communities call themselves sanctuary or safe cities, and others approved measures to limit their cooperation with federal immigration enforcement and promote themselves as welcoming places for the foreign born. Often seen as a new tactic in the fight against Trump’s immigration policies, this movement has actually been around for more than forty years, and the Boston-Cambridge area was a seedbed of these efforts from the beginning.

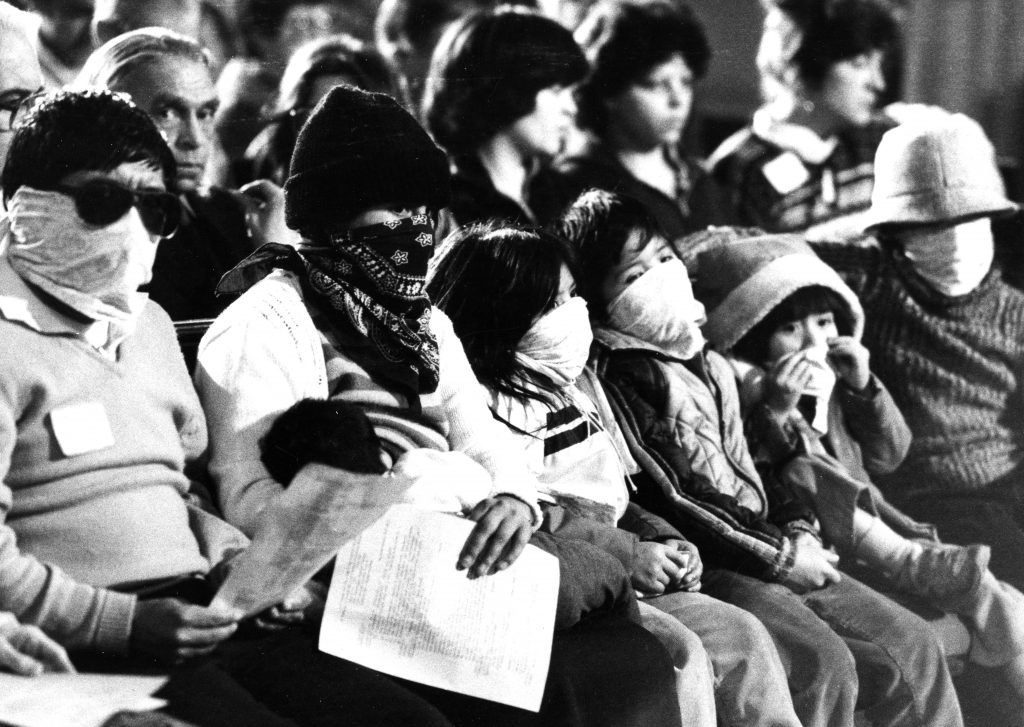

The sanctuary movement began in the early 1980s as churches and religious activists offered assistance and refuge to Central Americans fleeing civil wars and mass violence in El Salvador and Guatemala. With the Reagan administration supporting repressive military regimes in both countries, those fleeing violence were denied entry as refugees and many ended up crossing the border illegally. In 1982, a group of churches in Tuscon and San Francisco declared themselves sanctuaries for Central American refugees, sparking a movement that soon expanded across the country, including New England.

Cambridge became the local center of the movement, and in 1984 the Old Cambridge Baptist Church declared itself a sanctuary for those seeking asylum. Harboring a young Salvadoran woman who fled multiple rounds of torture by state authorities, church members held a two-week vigil with her and sponsored dozens of public forums where she and others gave testimony of their ordeal. The following year, local activists, working with the Cambridge Peace Commission, pressed the city council for a vote to make Cambridge a sanctuary city, meaning it would not cooperate with federal agents seeking to arrest and deport unauthorized migrants. It was the fourth such city in the country to do so, joining Berkeley, St. Paul, and Chicago.

In the years that followed, Boston, Somerville, and Chelsea followed Cambridge’s lead. Somerville adopted measures protecting immigrants in 1987, followed by Chelsea in 2007 and Boston in 2014. Elsewhere in Massachusetts, Springfield, Holyoke, Amherst, Northampton, Orleans, and Lawrence adopted similar provisions. Some call themselves “sanctuary” towns or cities, while others have avoided the label but adopted various “welcoming” policies to encourage immigrants’ integration and cooperation with police and local officials.

Such policies can include prohibitions on police asking individuals about their immigration status, sharing information with or performing the functions of federal immigration authorities, or transferring an individual to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in the absence of a judicial warrant. The city of Boston, for example, passed the Trust Act in 2014, which includes all of these provisions. The city continues to cooperate with Homeland Security on major crimes such as human trafficking, child exploitation, and drug and weapons smuggling. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court also affirmed in Lunn v. Commonwealth (2017) that there is no basis under state law for police or courts to detain a person solely at the request of ICE and without a criminal warrant.

President Donald Trump has made repeated attempts to withhold federal funds from so-called sanctuary cities through executive orders. In 2017, Chelsea and Lawrence filed suit against Trump’s first executive order, but it was dismissed after Joe Biden became president. Following Trump’s second executive order in 2025, Chelsea sued again, joined by Somerville. The outcome of these lawsuits remains to be seen and will be carefully watched.