Italian saint’s festival on Hanover Street in the North End, ca. 1930. Leslie Jones, Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library.

The North End is Boston’s oldest and most iconic immigrant neighborhood. Its proximity to the waterfront, transatlantic commerce, and the city’s downtown markets made it an enduring gateway for new arrivals from Ireland to Russia. But it was Italians who proved to be the neighborhood’s most important denizens in the twentieth century. Known as Boston’s Little Italy, the North End’s rich history continues to attract millions of tourists each year.

One of colonial Boston’s first residential areas, the North End became home to some of the town’s most elite families of the eighteenth century, including those of Governor Thomas Hutchison and Paul Revere. After the revolution, however, the exodus of loyalists and the migration of elite families to Beacon Hill ushered in a period of decline in the North End. As property values dropped, English and German migrants took up residence as well as newly arrived Irish who began to settle there in the 1820s. With the founding of St. Mary’s Catholic Church on Endicott St. in 1836, the city’s first Irish enclave grew up around the parish.

The Irish of the Famine Era

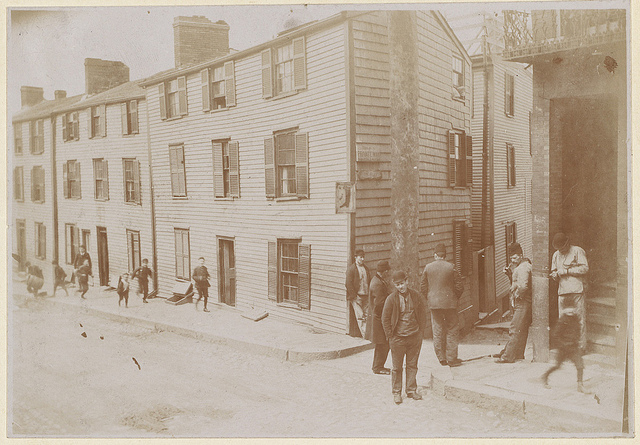

As the Great Famine dramatically accelerated emigration from Ireland, Irish newcomers began settling around North Square in the 1840s. To accommodate the influx and recoup income, landowners broke up the old mansions into boarding houses and tenements. Irish settlement thus expanded northward, and by 1850 the Irish made up more that 50 percent of North End’s population. Living conditions here were the worst in the city. Grinding poverty, overcrowding, and poor sanitation led to epidemics of smallpox and cholera, while drinking, violence, and prostitution became common features of North End life in these years.

After the Civil War, the Irish remained dominant but had to share the neighborhood with newcomers, mainly Russian and Polish Jews and Italians who first arrived in the 1860s and 1870s. By 1895, these two groups together would outnumber the Irish. Jews settled in a triangular area between Hanover, Endicott and Prince Streets, establishing a cluster of synagogues and businesses along Salem Street.

The Rise of Little Italy

Italians arrived around the same time, but their greatest growth occurred a few years after the Jewish surge. Early Italian arrivals in the 1860s were mainly Genoese from the north who settled around Ferry Court (near the current entrance to the Sumner Tunnel). Southern Italians from provinces such as Sicily, Calabria, and Campania followed a decade or two later. They settled along North Street and especially on North Bennett Street, where St. John the Baptist Catholic Church opened in 1843 to serve both Italian and Portuguese immigrants. Nearby, a small Portuguese community had sprung up on Fleet Street, an enclave of several hundred Azoreans that flourished between the 1880s and the First World War. Likewise on Commercial Street, a small settlement of Greek immigrants was evident around its restaurants and coffeehouses.

Such distinct ethnic enclaves were typical of the North End around the turn of the century. Newly arrived Jews, Italians, Portuguese, and Greeks sought familiarity and support among co-ethnic businesses, religious institutions, and social organizations. Likewise, the newcomers’ arrival created turf pressures with existing Irish residents who sometimes responded with violence and resentment. Ethnic enclaves thus provided protection amid social instability and growing intergroup tensions.

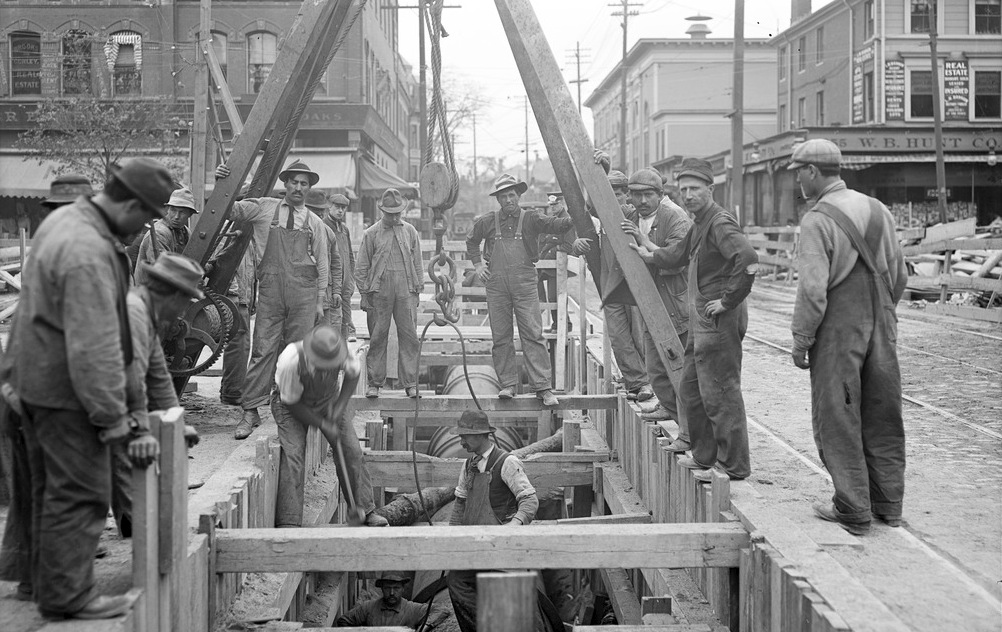

Many North End immigrants worked locally in small factories and on the waterfront unloading ships or moving freight. Others worked in the produce, meat, and fish markets at Faneuil Hall and Quincy Market or branched out on their own as street peddlers or shopkeepers. Portuguese and Sicilians came to dominate the local fishing fleets, while other Italians, like the Irish before them, were heavily concentrated in unskilled labor.

After 1900, the Italian presence in the North End increased as Jews moved out to the South End, West End, and Roxbury. By 1920, Italian immigrants and their children made up roughly 90 percent of the North End’s population and owned more than half of its residential property. The bustling neighborhood became known as Little Italy during these years and had one of the highest population densities in the world.

Decline and Revival

By the 1930s, however, the North End’s population began to decline as restrictive legislation reduced immigration and the area’s Italian and Italian American residents moved out to East Boston, Chelsea, and other northern suburbs. Remaining Italian residents—mainly the older generation—faced continued deterioration of the housing stock and major disruptions caused by the construction of the Central Artery and the Callahan Tunnel in early 1950s. More than a hundred families in the path of these projects lost their homes to the wrecking ball.

The fate of the North End improved in 1970s as the historic neighborhood attracted new investment around the bicentennial, but gentrification and luxury development made life increasingly unaffordable for the area’s older residents. Although the neighborhood has managed to attract some recent Italian professionals who can afford its steep rents, its ethnic character lives on mainly through its Italian stores and restaurants that have become one of the city’s most popular tourist attractions.

Works Cited

Goldfield, Alex R. The North End: A Brief History of Boston’s Oldest Neighborhood. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

Puleo, Stephen. The Boston Italians. Boston: Beacon Press, 2007.

Sarna, Jonathan D. and Ellen Smith. The Jews of Boston. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

Todisco, Paul J. Boston’s First Neighborhood: The North End. Boston: Boston Public Library, 1976.

Woods, Robert A. Americans in Process: A Settlement Study. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1902.