Cast members of the theatrical production “One Sunday Afternoon” celebrating at the Russian Bear Restaurant on Newbury Street in December 1933, just days after the end of Prohibition. This restaurant opened a year earlier under the ownership of Mrs. L.B. Mandova, a refugee from St. Petersburg. The Russian Bear served borscht, bliny, pieroshki, and other specialities in an ambiance that evoked the czarist days of pre-revolutionary Russia. Courtesy of Boston Herald-Traveler Photo Morgue, Boston Public Library.

One of the most visible manifestations of immigrant cultures is food. With the arrival of thousands of newcomers to cities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, ethnic groceries and restaurants were some of the first signs of distinctive food cultures that both nourished immigrant communities and piqued the interest of native-born residents. This surge in immigration coincided with the rapid growth of commercial restaurants in Boston and other US cities, and immigrants were key players in this culinary revolution.

One of the most visible manifestations of immigrant cultures is food. With the arrival of thousands of newcomers to cities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, ethnic groceries and restaurants were some of the first signs of distinctive food cultures that both nourished immigrant communities and piqued the interest of native-born residents. This surge in immigration coincided with the rapid growth of commercial restaurants in Boston and other US cities, and immigrants were key players in this culinary revolution.

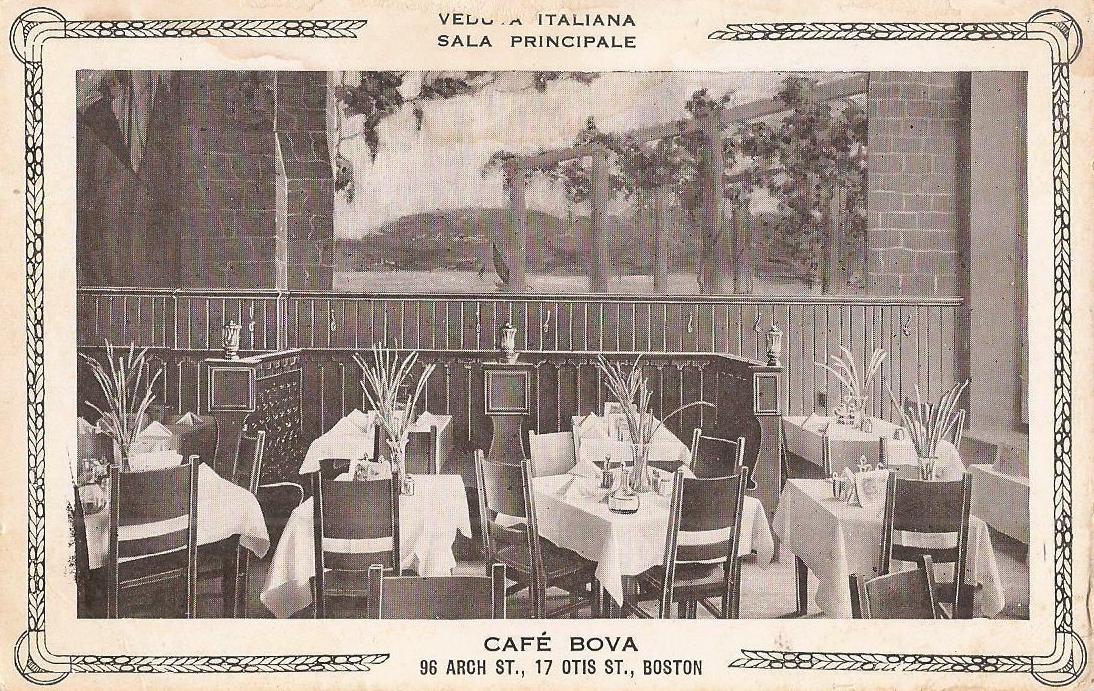

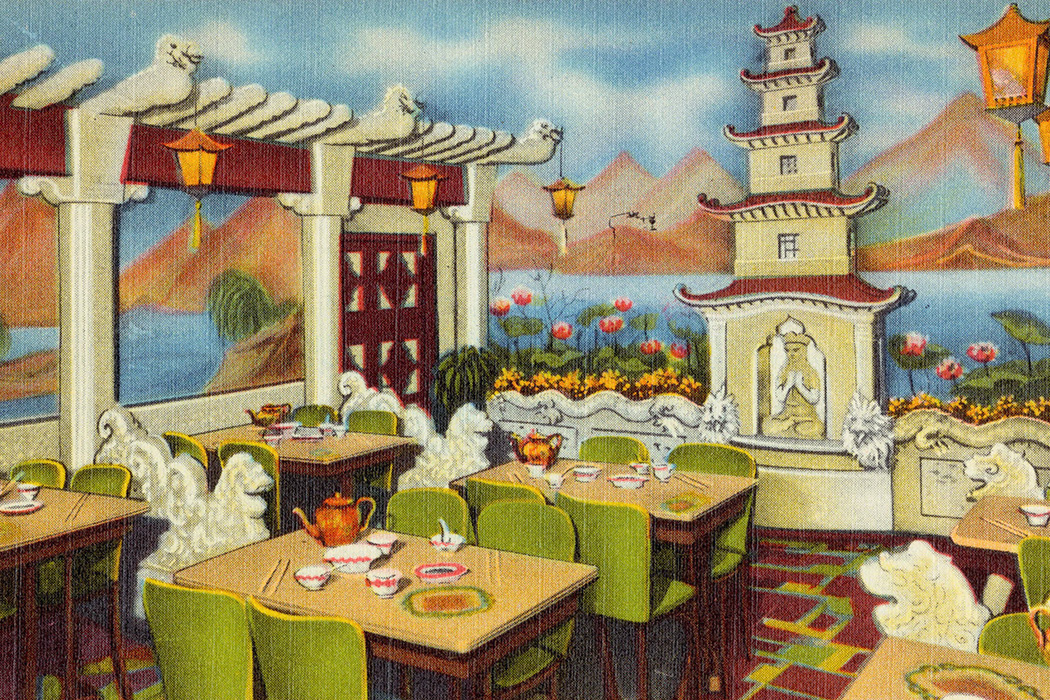

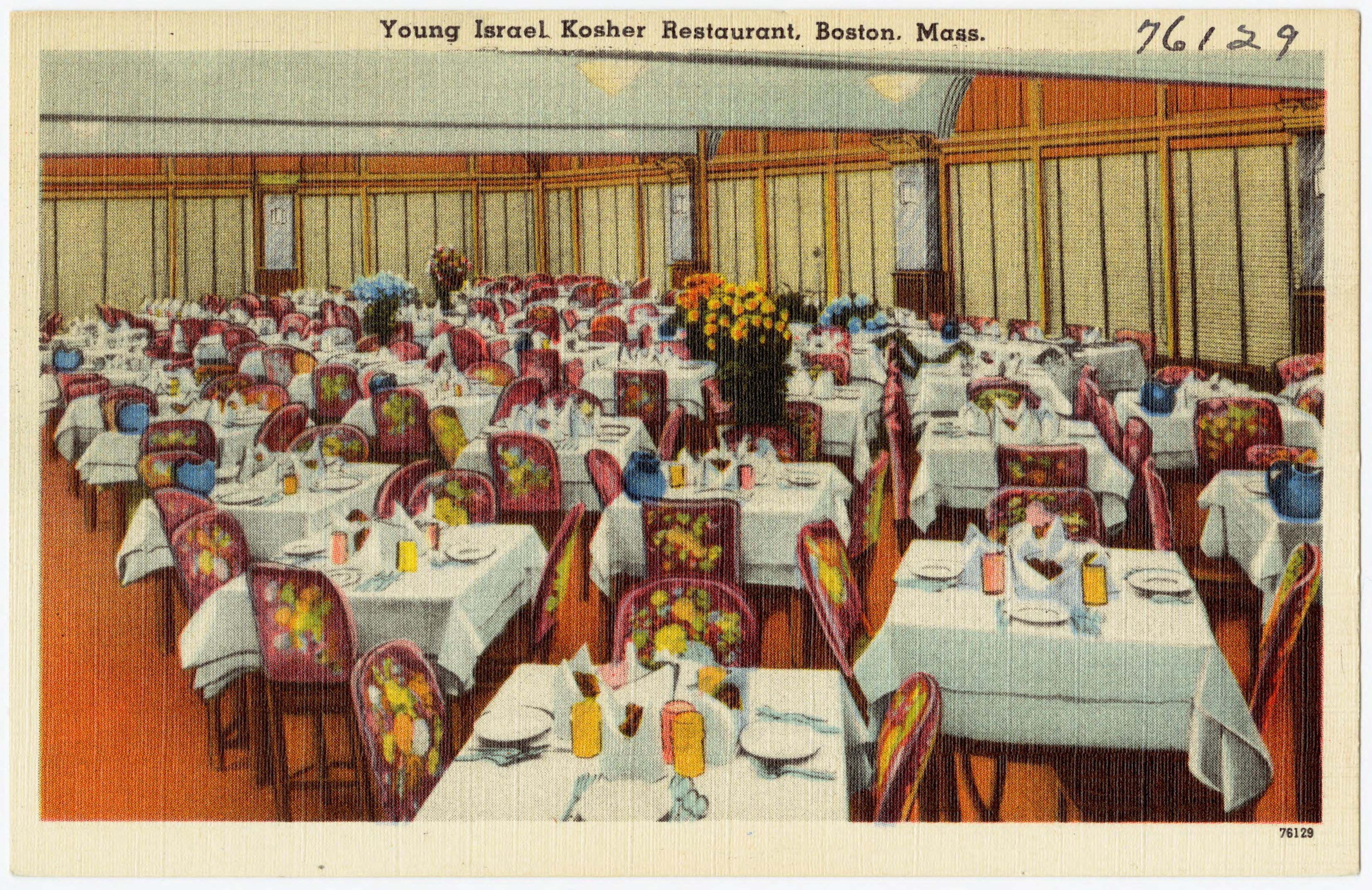

Records of the Boston Licensing Board between 1909-1937 show that foreign-born restaurant owners outnumbered native-born owners, holding a majority of the licenses issued for common victualers (food purveyors) across the city. Restaurants offered economic opportunities for immigrants as small business owners, but they were also a way to preserve their culture and serve their community with familiar foods and customs from home.

Records of the Boston Licensing Board between 1909-1937 show that foreign-born restaurant owners outnumbered native-born owners, holding a majority of the licenses issued for common victualers (food purveyors) across the city. Restaurants offered economic opportunities for immigrants as small business owners, but they were also a way to preserve their culture and serve their community with familiar foods and customs from home.

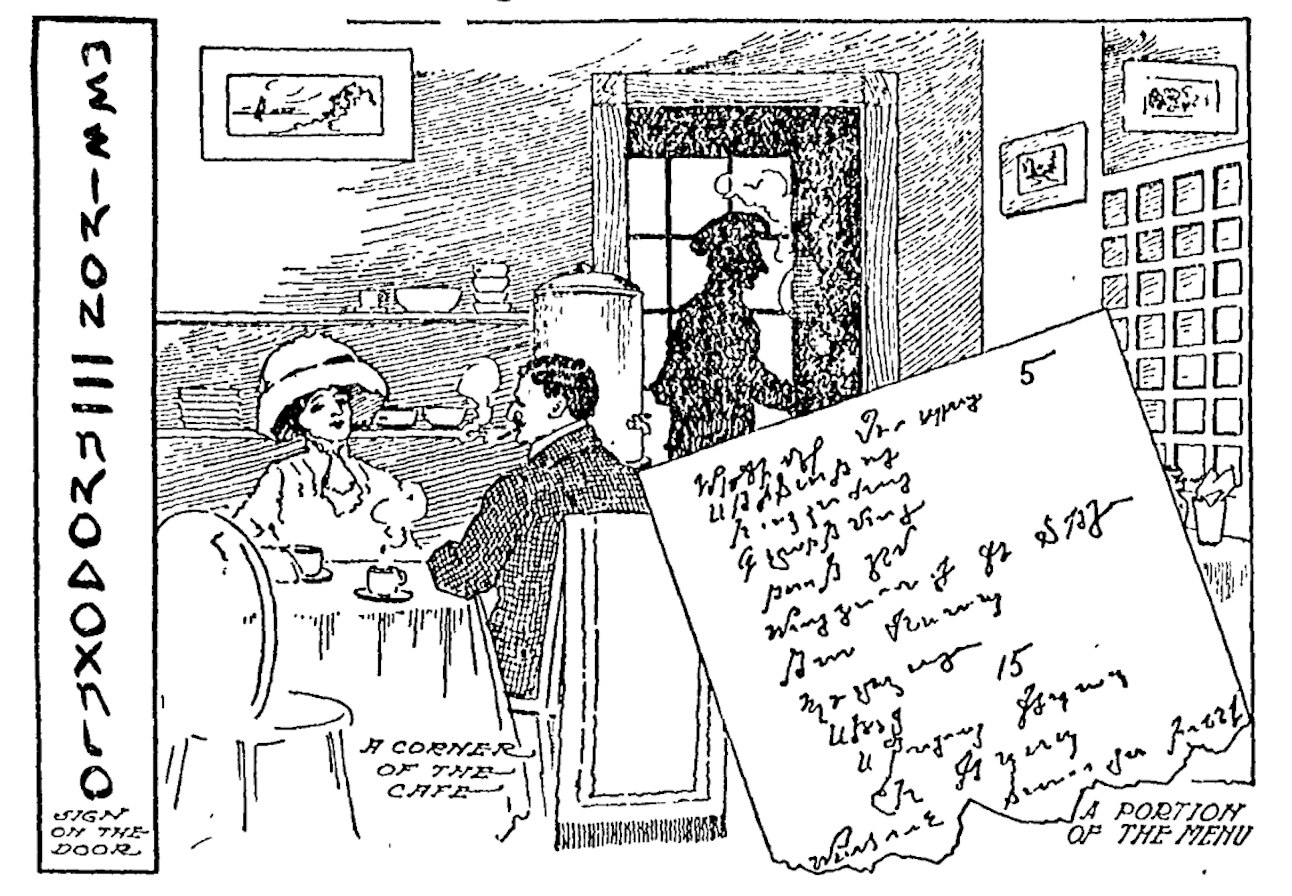

But many also sought wider patronage among other immigrants and native-born alike. As Boston expanded outward into streetcar suburbs around the turn of the century, immigrants sought to tap the market of workers who commuted to downtown and other commercial/industrial districts by opening a spate of inexpensive lunchrooms that served both American and ethnic foods. Others catered to an evening crowd of theater goers and slummers, providing “exotic” ethnic fare and ambiance for affordable prices during late night hours. The most successful opened large banquet halls that provided live music and dancing along with the ethnic fare. As native-born Bostonians sampled different foods and dining traditions, what was once considered “ethnic” was gradually absorbed into American culture as restauranteurs catered to a wider urban clientele.

Who Were the Immigrant Owners?

Some immigrant groups were particularly drawn to the restaurant business, as data from the Boston Licensing Board shows. While Canadians and Germans owned the largest number of restaurants in the city in the late 19th century, Russian Jews, Italians, and Greeks became the dominant operators in the early 20th. Chinese, Armenians, and Albanians also opened a significant number of establishments given their smaller numbers in the city. Surprisingly, the Irish–Boston’s largest foreign-born group–were initially not very prevalent in the food business even though they were well known as saloon and bar owners. By contrast, Greeks were one of the two largest national groups owning restaurants, even though their total population in the city of Boston was relatively small.

Mapping the Restaurants

We can see the rise and expansion of ethnic restaurants in Boston in this critical period through maps showing immigrant-owned establishments in 1895 and 1926. Drawn from the city directories for those years, the data do not represent all of the city’s restaurants, but rather a snapshot of what was likely a large sample of the total. We created a data set of these restaurants and their owners (sometimes searching through tax records to locate the owners’ names) and then researched them through census and immigration records to determine their nativity. We then created maps of the restaurants owned by foreign-born individuals using ArcGIS Online. The following two maps show the diffusion of Boston’s immigrant-owned restaurants over a 30-year period, illustrating the dramatic change in both immigration and ethnic restaurants between the 1890s and the 1920s. Click on the legend to toggle between different groups or on map points to see owner information.

Zoom out or scroll across map to see more restaurants (318 total). For further discussion of restaurants owned by different ethnic groups, please click feature boxes below.

Global Eats was created by students at Boston College in the 2021 course, Street Life: Urban Space and Popular Culture. Special thanks to Lila Zarrella for additional research and editing and graduate students in the Digital Humanities Certificate program who helped develop the maps and data visualizations: Elizabeth Bloor, Emily Coello, Bailey Lemoine, Sam Hurwitz, and Meghan McCoy. Bee Lehman, Matt Naglak, and Melanie Hubbard of the Digital Scholarship Group provided expert technical assistance. We are also grateful to Marta Crilly at the City of Boston Archives who helped us locate tax records that identified some of the owners of the restaurants.