Corner of Dudley and Warren Streets (Dudley Square) in 1856, as Irish and other immigrants were first moving into this emerging streetcar suburb. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library.

Founded by English colonists of the Massachusetts Bay Company in 1630, Roxbury was originally a sprawling town that included the present-day neighborhoods of West Roxbury and Jamaica Plain. During the 17th and 18th centuries, Roxbury gradually evolved from a rural satellite of Boston into an early industrial community. Mills, tanneries, and quarries that mined the town’s distinctive Roxbury puddingstone marked the landscape by the time of the American Revolution. While the completion of a horse-drawn bus line in 1820 and the Boston-to-Providence Railroad in 1835 helped to turn Roxbury into a fashionable suburb for Boston’s Yankee elite, new immigrants soon followed.

Foremost among these were the Irish, who remained a dominant presence in the neighborhood for the next century. Recently unearthed headstones near the site of St Joseph’s, Roxbury’s first Catholic church, show that a number of the town’s famine-era Irish came from County Donegal. Roxbury’s 19th-century Irish worked in factories as well as in day labor, domestic service, and in a number of trades. By the turn of the 20th century, they had transformed several blocks along Dudley Street into a cultural hub packed with dance halls and performance venues like Hibernian Hall. They also formed a substantial enclave around Mission Hill, named after the Mission Church founded by the Redemptorist Fathers in the 1870s.

Mission Hill was also home to an expanding German community beginning in the middle of the 19th century. Breweries and other German-operated businesses proliferated along Stony Brook, while tenements and row houses accommodated the neighborhood’s growing numbers of industrial workers. Eager to incorporate these new industries into the city, Boston annexed Roxbury in 1868. By 1900 Roxbury was home to a strikingly diverse array of immigrants from Europe and the Americas: Irish, Germans, Jews, Scandinavians, Italians, Latvians, and a substantial enclave of Maritime Canadians, who briefly became Roxbury’s largest immigrant group in the first decade of the 20th century.

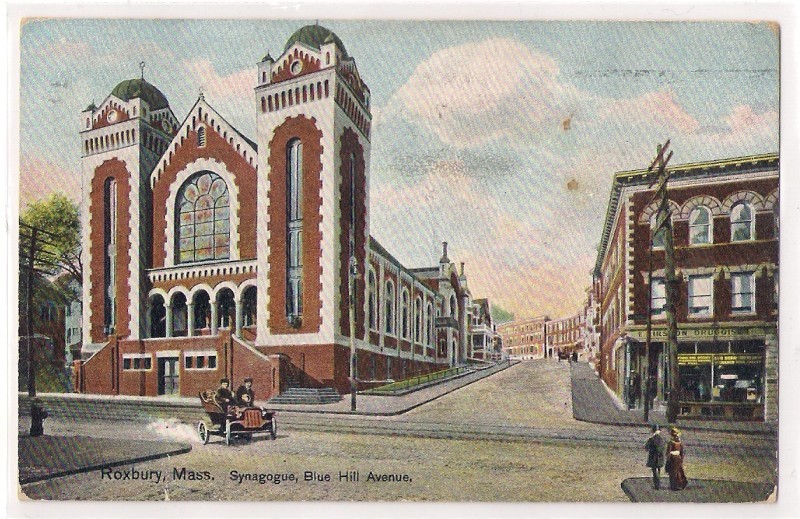

Ten years later, Roxbury’s rising Jewish population had become the dominant presence in the neighborhood. The first wave had begun arriving in the 1870s, as families that had found a measure of success in the North and South Ends moved south to the “first suburbs” of Roxbury and Dorchester. By the 1890, synagogues and kosher food suppliers were common sights in the Grove Hall area. The first two decades of the 20th century saw a second influx of Jewish immigrants, many of them fleeing persecution in the western provinces of the Russian Empire. To accommodate these new arrivals, temples like Adath Jeshurun (1906) and Mishkan Tefila (1925) proliferated throughout the neighborhood. Jews remained a dominant group in Roxbury until World War II, when a second migration began to western “second suburbs” like Newton and Brookline.

Roxbury’s ethnic composition changed once again in the middle decades of the 20th century. Beginning in the 1930s, native-born African Americans who had previously lived in Beacon Hill and the South End, as well as new immigrants from the Caribbean, came to dominate Lower Roxbury and the old Jewish neighborhood around Fort Hill. West Indians, many of whom worked as domestics, had a small but growing presence in Roxbury by the end of the Depression decade, and the ongoing migration of Jamaicans and Barbadians during and after World War II helped transform Roxbury into one of the Northeast’s most prominent Black communities. Other factors contributed to the midcentury demographic shift, too: redlining, white flight, and blockbusting by real estate groups further cemented Roxbury’s status as a predominantly Black neighborhood by 1970.

The neighborhood’s Latino presence also grew substantially in the postwar decades. Dominicans began arriving in the 1950s; migration accelerated after the 1961 assassination of Rafael Trujillo and the ensuing political instability. The Puerto Rican population in Roxbury also grew in the late 1950s and 60s, and a number of community organizations formed to accommodate the neighborhood’s rising Spanish-speaking population. La Alianza Hispana community center was founded in 1970 to provide the neighborhood’s growing numbers of Puerto Ricans and Dominicans with Spanish-language services. Puerto Rican Pentecostals founded the Canaan Defensores de la Fe in 1966, while the evangelical Center for Urban Ministerial Education provided preachers with Spanish-language instruction beginning in 1976.

In recent decades, newcomers from the Caribbean have continued to account for much of the immigration to Roxbury. The Dominican community has expanded since 1990 to become the neighborhood’s largest immigrant group by a wide margin; many moved from Jamaica Plain as gentrification and the repeal of rent control in 1994 drove up property values. Meanwhile, Africans constitute a smaller, yet growing, segment of the foreign-born population. Cape Verdeans, for example, were an almost invisible presence in the neighborhood in 2000, but by 2015 they were second only to Dominicans. St. Patrick Catholic Church on Magazine Street has become an important religious center for both of these groups.

Since the 1990s, Africans from Ethiopia, Nigeria, Kenya, and Somalia have also arrived in a small but steady stream. These immigrants have opened new restaurants and businesses in the community as well as helping establish new churches and a mosque. Following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the Islamic Society of Boston Cultural Center—then under construction in Roxbury Crossing—became the center of a major controversy that lasted for most of the decade. The mosque ultimately opened in the summer of 2009 and now represents more than sixty nationalities. These newer groups, together with older African American and Latino residents, have come together to form vibrant community organizations like the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative, which administers a number of essential neighborhood programs and works to empower Roxbury’s residents in local politics.

These groups are at the forefront of Roxbury’s rich immigrant past. Today, this growing immigrant neighborhood—about 28 percent foreign born, mirroring the statistics for Boston as a whole—remains on the frontline of ongoing struggles around immigration, gentrification, housing, and development.

–Samuel Davis

Sources and Further Reading

Gamm, Gerald. Urban Exodus: Why the Jews Left Boston and the Catholics Stayed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Johnson, Marilynn. The New Bostonians: How Immigrants Have Transformed the Metro Region since the 1960s. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015.

Johnson, Violet Showers. The Other Black Bostonians: West Indians in Boston, 1900-1950. Bloomingon: Indiana University Press, 2006.

Roxbury Historical Society, “About Roxbury.”

Sarna, Jonathan D. and Ellen Smith. The Jews of Boston. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

Woods, Robert A. and Albert J. Kennedy, The Zone of Emergence: Observations of the Lower Middle and Upper Working Class Communities of Boston, 1905-1914. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1962 (chapter 5 on Roxbury and Dorchester).