In 1894, the Boston Globe reported that the city had only one Jewish restaurant, located on Hanover Street in the North End. By the 1920s, however, there were more than three hundred Jewish-owned restaurants across the city, the most run by any foreign-born group at the time. As migration from Russia and Eastern Europe surged in the early twentieth century, and as the Jewish community expanded across the North, West, and South Ends, so too did the kosher groceries and restaurants that served this fast-growing population. As our 1926 map shows, these eateries were not limited to any one area of the city but stretched from downtown Boston to Roxbury, Mattapan, and out to Brighton.

In 1894, the Boston Globe reported that the city had only one Jewish restaurant, located on Hanover Street in the North End. By the 1920s, however, there were more than three hundred Jewish-owned restaurants across the city, the most run by any foreign-born group at the time. As migration from Russia and Eastern Europe surged in the early twentieth century, and as the Jewish community expanded across the North, West, and South Ends, so too did the kosher groceries and restaurants that served this fast-growing population. As our 1926 map shows, these eateries were not limited to any one area of the city but stretched from downtown Boston to Roxbury, Mattapan, and out to Brighton.

From Grocers to Restaurateurs

The hurdles that accompanied assimilation motivated Jewish immigrants to enter the grocery and restaurant business in this era. Small business ownership was a goal of many Jewish newcomers, and the growing market for kosher foods among the mostly orthodox Jewish community provided a unique opportunity. Notable Jewish grocers during this time included Kane’s Kosher butcher shop in the West End, Wholesale Foods Company, and the “Greenie” store in the North End, a predecessor of what would become the Stop & Shop grocery chain. The grocery industry propelled owners to expand their offerings to serve customers food that could be eaten on the property rather than simply purchased and eaten elsewhere.

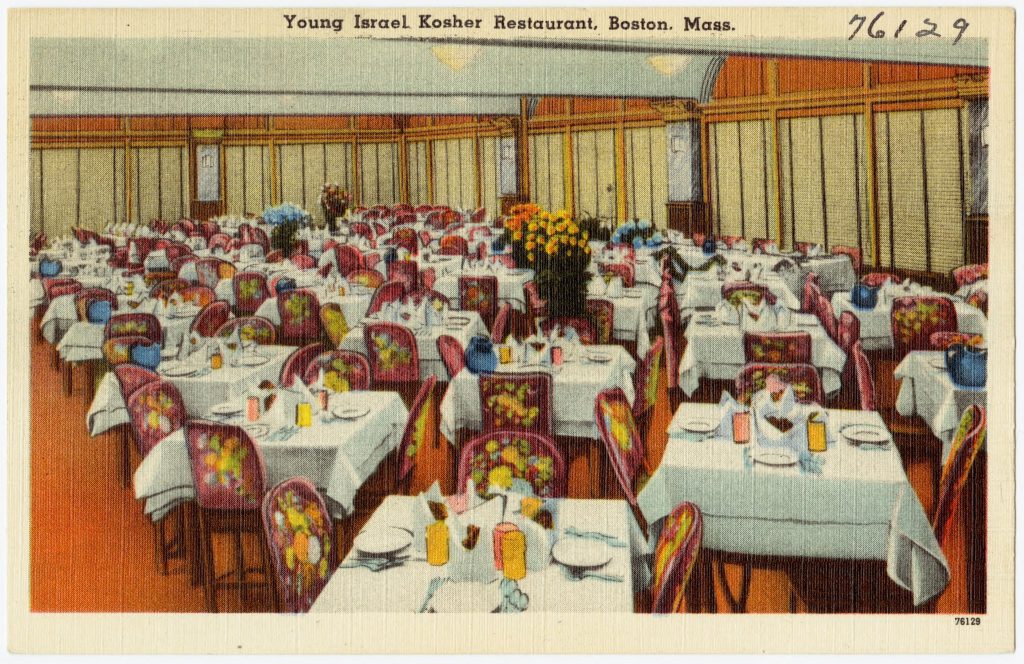

The beginnings of the Jewish restaurant industry in Boston reflected national trends in which Jewish groceries progressed towards becoming more modern full-service restaurants. Around the turn of the century, delicatessens began to make the shift toward sit-down service, adding tables in and outside of the stores. Some of the earliest Jewish delicatessens began adding on-site dining, but their offerings were extremely limited, prices were inexpensive, and the decor was simple and functional. As these restaurants gained popularity, they transitioned to full service restaurants that offered Jewish specialties such as smoked meats, bagels and lox, potato knishes, borscht, blintzes, and kasha varnishkes.

As Jewish businesses grew, so did their consumer base. Downtown Jewish restaurants in particular became well known for how late they kept their doors open. In 1915, multiple newspaper articles discussed how some non-Jewish restaurants felt it was unfair that Jewish eateries stayed open late and thus could bring in more revenue. They called for Jewish restaurants to observe traditional closing times and even urged the city to withhold licenses from those who refused. The city’s Licensing Board did in fact order 115 smaller businesses to close by midnight, and 41 of those restaurants were Jewish-owned. The proprietors responded that such measures were discriminatory, allowing larger chain restaurants to monopolize the late night trade.

During the 1920s, various Jewish restaurants promoted themselves in newspapers such as the Boston Herald. In September of 1925, the Wellworth Restaurant began advertising in the Herald as the first kosher restaurant in Boston, using this distinction as a marketing strategy. Establishments such as Prime Restaurant and Park View Restaurant also served traditional kosher and Jewish meals.

The Impact of a Kosher Diet

Most customers of these early Jewish restaurants were immigrants from Russia and Eastern Europe. Jewish patrons relied on these restaurants and groceries not only out of necessity–since they provided the foods for a kosher diet–but also out of a sense of loyalty to shared Jewish values. Customers knew they could rely on these restaurants to serve proper dishes for Jewish holidays, such as tishpishti on Rosh Hashanah, kreplach on Simchat Torah, or latkes on Hanukkah. Years later, one Boston delicatessen owner revealed that many elderly Jews continued to patronize her deli until their final days, claiming “they’re practically on respirators, but they want that last taste of deli before they die.”

The consumption and sale of food greatly shaped the experience of Jewish immigrants in America. As historian Hasia Diner notes, “food embodied a palpable manifestation of Jewish conceptions of divine will,” and the salience of kosher meals and marketplaces brought Jewish communities closer together, both physically and socially. These spaces for kosher food began to shape urban community life for Jews in Boston, and for some immigrants, opened up new forms of public consumption.

In addition to dietary factors, kosher restaurants also served as cultural touchstones for immigrants, symbolizing ethnic community and continuity. Kosher delicatessens exemplified something authentically Jewish and eventually, as writer Ted Merwin put it, “eating in a delicatessen became almost a religion unto itself.” Over time, as the number of Jews who kept kosher decreased, the number of kosher delicatessens across America actually increased, revealing the cultural importance of these restaurants to the Jewish community. By the 1920s and 1930s, though, many of these establishments in Boston were no longer strictly kosher, prompting complaints from local orthodox Jews about the lack of authentic kosher restaurants in the city.

The G&G and Beyond

One of the most prominent non-kosher Jewish eateries was the G&G Delicatessen, located on Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester. Owned by Charles Goldstein and Irving Green, the G&G opened in 1921 and soon became the main gathering place for the Jewish community of Dorchester and Mattapan. By the 1930s, the G&G had become an important political nexus in the city; the Jewish Advocate noted that every US presidential candidate from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Dwight Eisenhower had visited the delicatessen. Candidates for local and national office and their supporters would attempt to rally last-minute votes at the G&G, even on election night, highlighting the importance of the institution to the Jewish community and Boston politics more broadly. The G&G closed its doors permanently in 1971, as the Jewish population of Dorchester declined.

Although the 1920s-1930s heyday of the Jewish restaurant in Boston may have passed, kosher restaurants and Jewish delis have an ongoing presence in greater Boston, many with avid followings. As a growing number of Jews moved out of the city in the post-World War II decades, the number of Jewish restaurants in Boston dwindled, as many closed while others followed their customers to the suburbs. The overall decline in the number of Jewish-owned restaurants and delicatessens has been evident in many cities, likewise due to suburbanization and owners not wanting their children to have to work the long hard hours that running a restaurant entails.

Today, however, in suburban communities with substantial Jewish populations, such as Brookline, Newton, Sharon, and Marblehead, Jewish delis and bagel shops continue to flourish. Moreover, a newer wave of Jewish and Israeli immigrants have expanded the repertoire and culinary styles of Jewish-owned restaurants in Boston, bringing Middle Eastern-style foods and more modern and diversified kosher menus.

–Stephanie Wang, Mikayla Sanchez, Ling Han Su, and Lila Zarrella

Works Cited

“Charles Goldstein, Co-Founder of Noted Delicatessen, Dies.” Jewish Advocate, July 24, 1958.

“Denial by Board of Licenses: Claim Hebrew Restaurants Not Discriminated Against,” Boston Post, May 6, 1915. Diner, Hasia R. Hungering for America: Italian, Irish, and Jewish Foodways in the Age of Migration. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Friedman, Samuel. “Seeks Kosher Restaurants Here.” Jewish Advocate. October 29, 1937.

“Lunchroom Owners Charge Unfairness: Declare Jews Are Discriminated Against in Order to Close Restaurants at Midnight.” Boston Post, May 5, 1915.

Merwin, Ted. Pastrami on Rye : An Overstuffed History of the Jewish Deli. New York: New York University Press, 2015.

O’Connell, James C. Dining Out in Boston: A Culinary History. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2016.