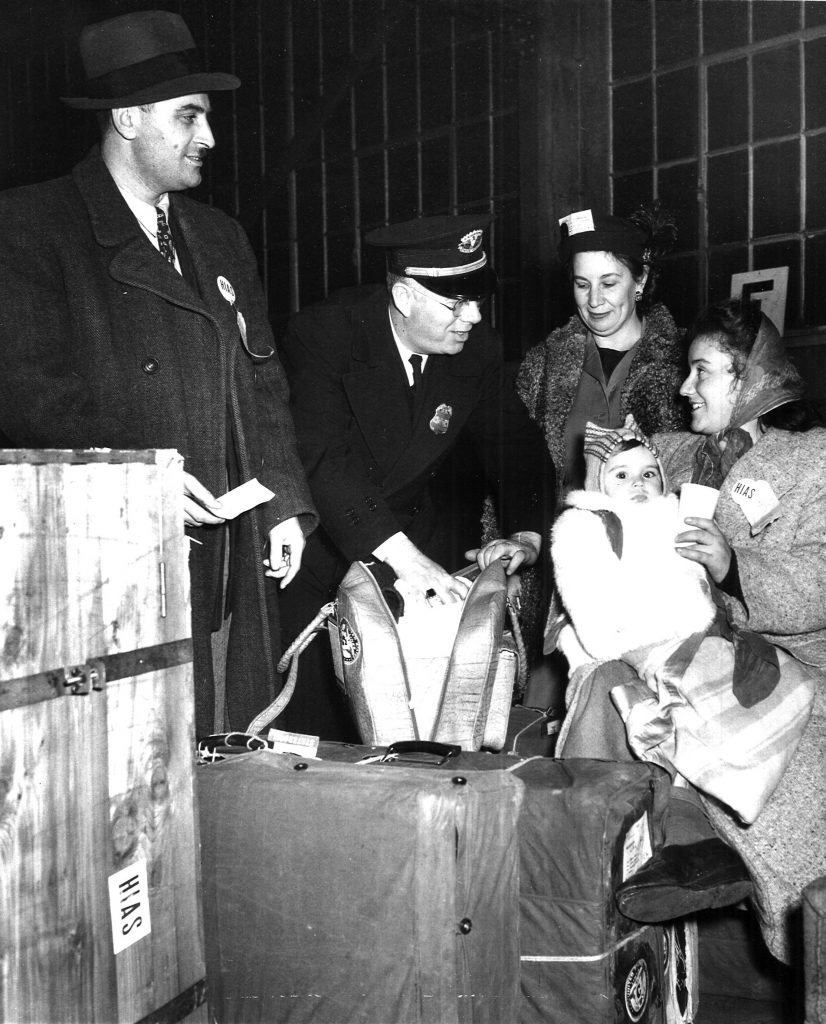

Passover seder provided by the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society for new arrivals at the East Boston immigration Station, 1921. Photograph by permission of the American Jewish Historical Society-New England Archives, Boston, MA.

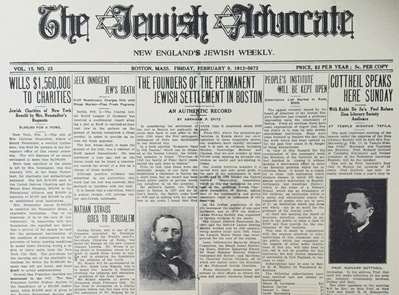

Although small numbers of Sephardic Jews passed through Boston in the colonial era, the city had no significant Jewish presence until the mid-nineteenth century. In the 1840s and 1850s, Jews from Poland and Germany began arriving, coming especially from the Prussian-ruled provinces of Posen and Pomerania. Fleeing economic deprivation and religious persecution, the new Jewish arrivals to the city numbered about a thousand on the eve of the Civil War.

Beginning in the 1880s, a much larger wave of Jewish immigrants arrived from the Pale of Settlement in Russia and Eastern Europe. During the nineteenth century, the Russian czars had confined Jews to this region and subjected them to religious persecution, expulsions, and forced military conscription. Passage of the May Laws in the 1880s made matters worse by forbidding Jews from owning or renting land outside of towns or cities and limiting their access to education. From 1881-1883 and again in the early twentieth century, Jews were also targeted in violent riots or “pogroms” that left thousand dead and caused many more to flee.

After World War II, a small wave of Holocaust survivors and other refugees were resettled in greater Boston through the efforts of local Jewish philanthropies such as the Boston Refugee Committee and Jewish Family and Children’s Services. Later, some of these same refugees and organizations would work to resettle Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s. Roughly 10,000 had settled in greater Boston by the early 1990s, and Jewish emigration from Russia and the former Soviet republics has continued into the twenty-first century.

Settlement

Prior to the Civil War, Jews from Central Europe originally settled in what is now the theater district and Park Square; they later fanned out across the lower South End. A second wave of Russian Jewish immigrants settled here as well, but the surge of new arrivals soon pushed Jewish settlement into the North and West Ends. The latter would become especially important: by 1910, roughly 40,000 Jews were living in the West End.

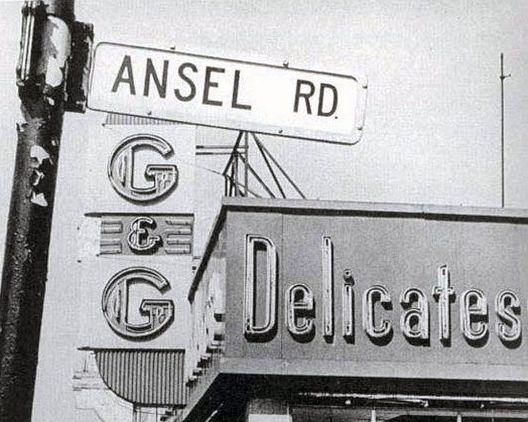

Back in Boston, prosperous Jewish merchants and their families had begun moving to the more bucolic Roxbury neighborhood in the late nineteenth century. Soon, middle and working class Jews followed. In the first half of the twentieth century, Jewish settlement spread progressively south along Blue Hill Avenue, from Roxbury to Dorchester and Mattapan. After World War II, many moved further out to suburbs such as Brookline, Newton, Swampscott, Marblehead, and Sharon, bringing their synagogues and other community institutions with them.

Work

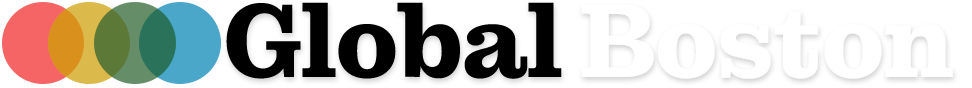

Early Jewish immigrants in Boston worked mainly as peddlers and tailors, with the most successful opening retail businesses or garment shops. The later Russian Jews were more likely to work in the region’s growing shoe and textile mills, but especially in the garment industry of the South End, shops often run by the older Jewish entrepreneurs. Like their predecessors, second wave migrants also worked as peddlers and small business owners, including a growing number who operated kosher groceries and restaurants. Others worked recycling rags, scrap metal and other industrial refuse. Despite these humble beginnings, many of their children were able to pursue education and advancement into white-collar professions. In the late twentieth century, Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union tended to be more highly skilled and educated than earlier groups. Many were professionals who found work in technology, engineering, and medicine.