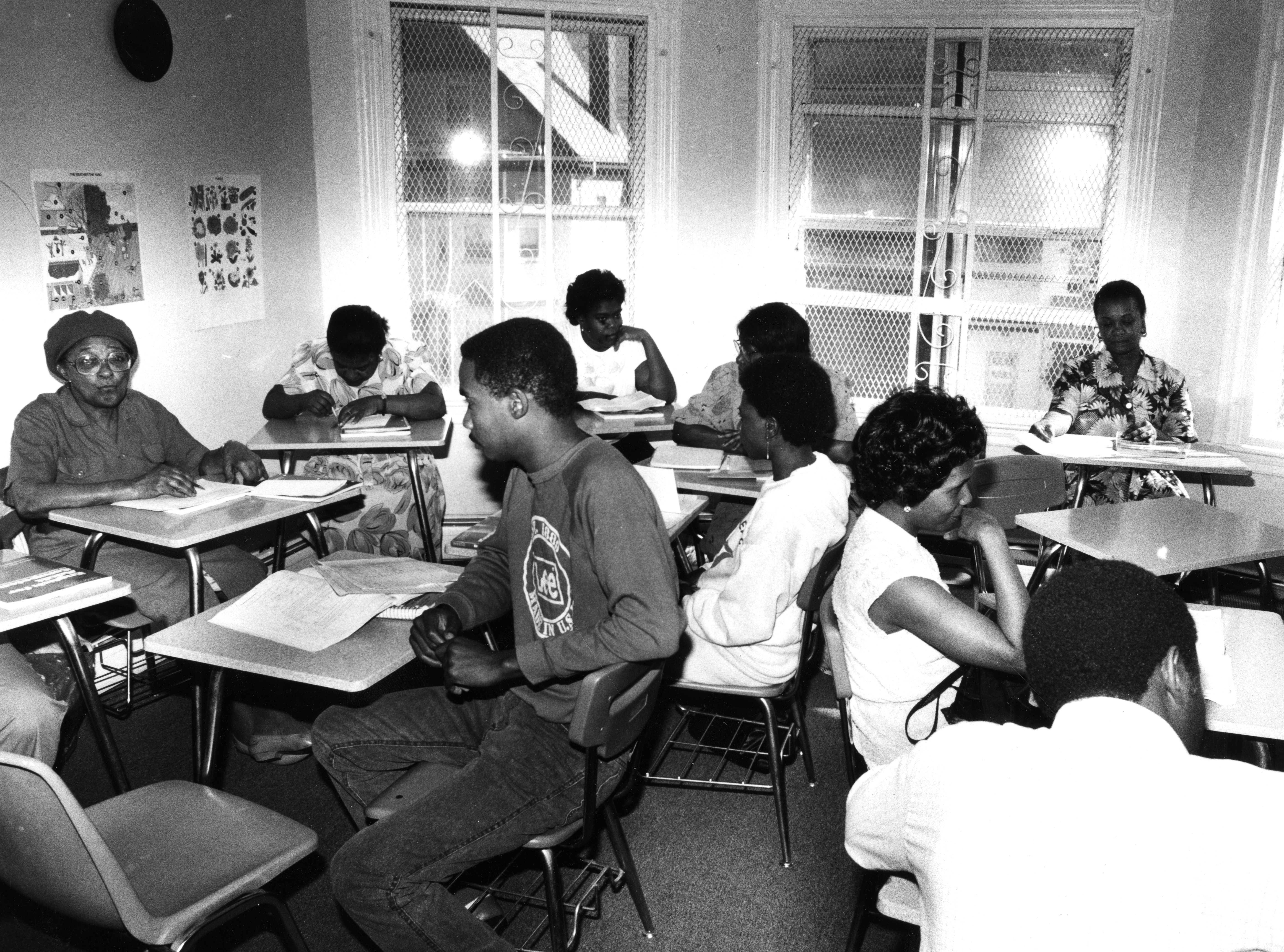

Haitian students at an ESL class at the Haitian Multi-Service Center in Dorchester, 1987. Courtesy of the Boston Globe.

Coming in search of higher education and professional opportunities, the first wave of Haitian settlers began arriving in Boston in the late 1950s and 1960s. Mainly professionals, artists, and intellectuals, the early arrivals were drawn from the island’s urban Catholic, French-speaking elite. Violent repression and human rights abuses under US-backed Haitian President Francois Duvalier (1957-1971) continued under his son Jean-Claude Duvalier (1971-1986), driving still more into exile. A more diverse group of Haitians arrived in Boston after 1980, including Kreyol-speaking middle-class and poorer migrants from both rural and urban areas of the island. The Haitian population also grew as a result of secondary migration from Miami and New York, with the region’s educational institutions as a major draw.

While political instability, violence, and poverty continued to fuel the Haitian diaspora after 1980, biased US refugee policies (that favored those from Communist countries) meant that a growing number entered as unauthorized migrants. Some were later granted asylum or Temporary Protected Status under the 1990 Immigration Act, including those fleeing the destructive hurricanes of 2004 and 2008, as well as the devastating earthquake of 2010. Following a lull in migration during the Covid-19 pandemic, Haitian immigration surged again as the country’s governmental functions collapsed in the wake of the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in 2021. Beginning in 2023, Haitians were among several groups who have ended up living in overcrowded shelters across the region. With a diasporic community that is now more than fifty years old, greater Boston is one of the top three destinations for Haitian immigrants to the United States, and Haitians make up the third largest foreign-born group in the city.

Patterns of Settlement

The city’s early Haitian settlers originally clustered around two Catholic parishes in south Dorchester. Still predominantly white in the 1960s, the parishes of St. Leo and St. Matthew in the Franklin Field (now Harambee Park) neighborhood soon became the center of Boston’s Haitian community. As the migrant population grew, settlement expanded southward into Mattapan, then a predominantly Jewish district. Beginning in 1968, Haitian home ownership in the area grew precipitously after the Boston Banks Urban Renewal Group instituted a federally backed home loan program for black buyers. By the 1980s, Mattapan Square had become the heart of the city’s Haitian community, anchoring a crescent of settlement that extended north up to Roxbury and south to Hyde Park. Across the Charles, a smaller Haitian community had developed in East Cambridge, but by the 21st century, gentrification and rising housing costs had convinced most new arrivals to look elsewhere.

Led by a growing professional class in the 1980s, Haitian immigrants also fanned out into surrounding suburbs. Most moved southward, with Randolph and Brockton becoming the two most popular destinations, but several thousand also moved north to Everett and Malden. By 2010, the majority of Haitian immigrants in the metro area lived outside of Boston and Cambridge.

Workforce Participation

Since their arrival in Boston in the late 1950s, Haitians have been concentrated in the healthcare professions and services. Some of the city’s pioneer settlers were doctors seeking advanced medical training and employment, while subsequent generations have been dominant in the nursing profession. Ranging from registered nurses to certified nursing assistants, the nursing professions employed roughly half of all women workers of Haitian descent in the Boston area by the early 21st century.

Haitian men have worked in a variety of occupations, from physicians and educators to transportation and food service workers. Working-class Haitian men have been particularly prevalent among taxi cab drivers. Some of them managed to purchase their own vehicles and medallions; they then leased their cabs to fellow Haitians, creating a niche in the industry. In recent years, though, most have worked for large taxi companies where contract-style labor has yielded long hours and low pay.