Postcard showing main dining room of Cafe Bova, a popular downtown Italian restaurant, 1912. Founded by Calabrian-born Antonio Bova in 1907, this cosmopolitan restaurant featured elegant tables, murals of Neapolitan scenery, and live Italian music. Its eclectic menu offered dishes ranging from spaghetti with “clam gravy,” to risotto Milanese, to New England boiled dinners.

In 1868, Boston’s first Italian-owned restaurant, Vercilli’s opened on Boylston Street. Interestingly, although Vercilli’s highlighted its Italian roots, it served mainly French and American food. For a period in the late nineteenth century, an “Italian” restaurant simply denoted that the owner or chef was Italian, but said nothing of the food. It was not until the 1890s–with the arrival of thousands of immigrants from southern Italy–that restaurants serving Italian cuisine became more prevalent in Boston. By the 1920s, there were several hundred Italian-owned restaurants, making Italians the third largest group of immigrant restauranteurs in the city.

In 1868, Boston’s first Italian-owned restaurant, Vercilli’s opened on Boylston Street. Interestingly, although Vercilli’s highlighted its Italian roots, it served mainly French and American food. For a period in the late nineteenth century, an “Italian” restaurant simply denoted that the owner or chef was Italian, but said nothing of the food. It was not until the 1890s–with the arrival of thousands of immigrants from southern Italy–that restaurants serving Italian cuisine became more prevalent in Boston. By the 1920s, there were several hundred Italian-owned restaurants, making Italians the third largest group of immigrant restauranteurs in the city.

To the North End and Beyond

The earliest Italian restaurants appeared in the 1890s in the North End, home to thousands of Italian men who crossed the Atlantic in hopes of finding work. Some took their meals in the residential hotels that sprung up to serve single men, offering food from their home regions of Campania, Sicily, and others. Italian grocery stores and bakeries also sprung up, offering familiar foods to take out. Some of these establishments began offering table service with daily menus posted on the wall. As our 1895 map shows, there were at least five Italian-owned restaurants clustered along North Street, stretching toward the docks where many newcomers worked.

Over the next several decades, a strong Italian ethnic enclave took root in this neighborhood, as many men sent for their families to join them and settled amid the familiar culture of the North End. Our 1926 map shows, there were upwards of fifteen Italian-owned restaurants in the North End, spreading outward from North Square to Hanover, Salem, and Commercial Streets. The map also shows a wider diffusion of Italian eateries across the city. East Boston, a newer area of Italian settlement, hosted at least four Italian-owned restaurants in 1926. Others, such as the Zappion Cafe and the Eliot Inn Italian Restaurant, were located in the downtown theater district where they catered to a broader American clientele.

What’s for dinner?

In the early 20th century, the food at Italian restaurants was often described in newspapers as being a novelty worth trying, quite different from other options in the city at the time. Most Italian restaurants were owned and operated by southern Italians and their menu reflected southern Italian staples, such as spaghetti with a garlicky red tomato sauce, known as “marinara” or “gravy.” Often these restaurants featured veal, poultry, pasta, and sauces that were all prepared with “great stress on the delicacy of flavor” and in a traditional manner, according to a Boston Globe article in 1906. Italians’ liberal use of garlic, in fact, played a crucial role in introducing this ingredient to the American palate.

As Italian eateries proliferated and spread downtown, the cuisine evolved to accommodate American tastes and available ingredients. This Italian American-style cooking included larger portions with more meat and fish–rare items in rustic Italian meals back home. Spaghetti with meatballs became a favorite, as did antipasto (an assortment of smoked meats, pickled vegetables, and cheese), minestrone soup, veal parmesan, and chicken cacciatore. Pizzerias such as Pizzeria Regina in the North End (established in 1926) and Santarpio’s in East Boston (1933) and also gained popularity, with pizza evolving from a simple takeout food to a sit-down family meal.

Although a majority of Italian restaurants in Boston were owned by southern Italians, racism and discrimination against the southern restauranteurs was common and affected public perceptions of their restaurants. In a 1904 Boston Herald article on the development of “Little Italy,” the writer noted that Neapolitan proprietors ran several “lower class” Italian restaurants that were “shoddy imitations of cheap American restaurants.” By contrast, the article noted, a nearby Bolognese restaurant owned by Ernesto Tassanari had more refined dishes and attracted a more “exclusive” crowd. Tensions between northern and southern Italian immigrants themselves were also evident, as restaurants like Tassanari’s refused to hire southern Italians for their staff.

Spaghetti and Slumming

Although most early Italian restaurants in Boston catered to the Italian community, many native-born bohemians began patronizing these restaurants as well, attracted to the “exotic” qualities of Italian food and people. These “slummers” found the tomato-based, vegetable-focused cuisine of southern Italians almost an antithesis to the “New England” way of eating. They were also struck by the exoticism of Italian culture and Italian people, who were viewed as an “in-between” race at the time. An 1894 Boston Globe article on commented on the colorful quality of local Italian servers, writing of the “buxom, black-eyes maidens” who spoke “fascinating broken English.”

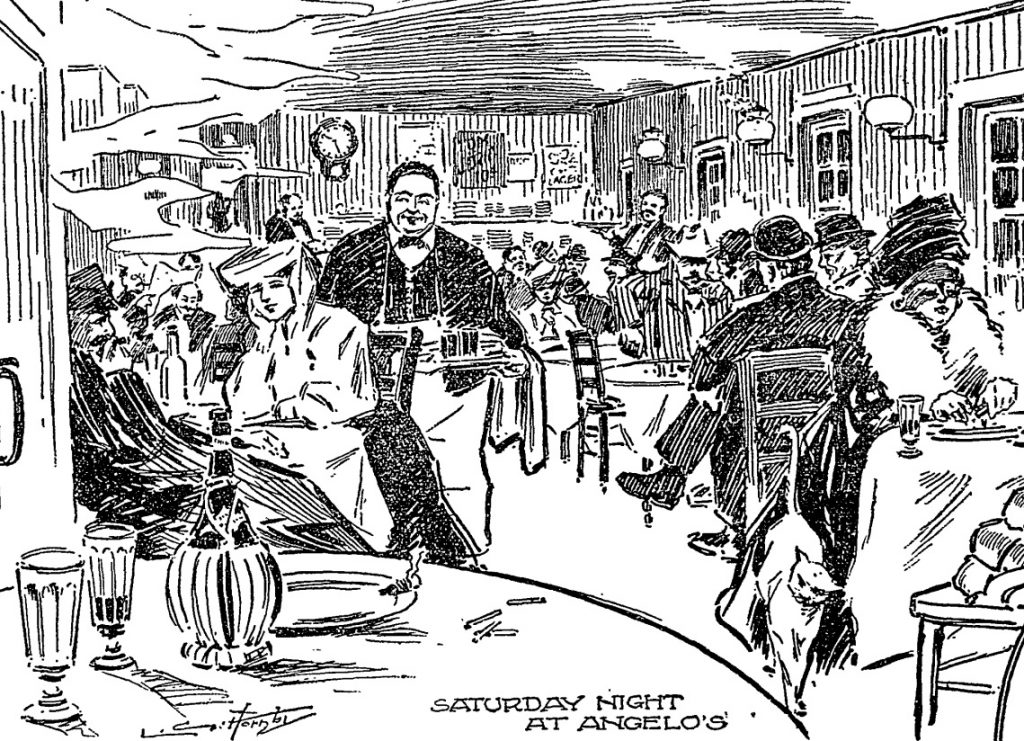

Italian restaurateurs soon began capitalizing on “exotic” depictions and stereotypes ascribed by slummers. As native-born Americans often associated Italians with ideas of tradition, family, and conviviality, some restaurant owners played up these characteristics. Proprietors often highlighted the connections to family within the restaurant, “where mama cooked, papa served [and] one always found… homely advice on how to bear life’s burden.” Local newspapers provided vivid accounts of proprietors such as Bimbo Funai, who was described as a cheerful, rosy man from Florence, loved by all and known for being both a great cook and a “jolly” personality. For their part, restaurateurs also catered to slummers by crafting a certain image of Italy within their restaurants, complete with traditional Italian musicians and “village-style decor” evoking images of the Mediterranean.

A look inside the Italian restaurant

Other restaurants sought to combine traditional Italian decor with American culture. Upon the opening of the Richmond House in Boston, owned by E.F. Palladino, the Boston Post described its elegant dining room “draped with the combined flags of Italy and America. On one side, Columbus discovered America, while his vis-a-vis was Washington reading the Declaration of Independence” on the opposite wall. Looking to create a more cozy atmosphere, the owner of the Tuscan Restaurant, Bimbo Funai, also linked Italian and American culture by hanging prints of the Italian royal family alongside photos of three generations of his family in Italy and America.

Increasingly though, downtown Italian restaurants crafted their appeal to fashionable American customers seeking late night entertainment. One place that cultivated such patronage was the Lorraine restaurant. Located next to the Shubert Theater downtown, the Lorraine advertised its menu as “a la carte from noon until midnight [with] dancing, cabaret, jazz band, and booths.” The Miami Restaurant, which served both Italian and American food, emphasized its alcoholic beverages, noting the restaurant offered choice liquors, cordials, wine, and beer with “mixed drinks a specialty” alongside “dancing till closing” with a 12-piece orchestra.

Such downtown establishments demonstrated the mainstream appeal of Italian American cuisine in the 1920s and 1930s, but few Italian immigrants would have patronized such upscale venues. Instead, they were more likely to dine at the cozier restaurants of the North End, of which there were dozens following the end of Prohibition, when wine could flow freely again.

The Italian Restaurant Today

Despite the diffusion and Americanization of the city’s Italian restaurants, Boston’s North End remained the hub of Italian cuisine, as it does to this day. Its pricier restaurants reflect a wider range of Italian culinary styles that continue to attract thousands of locals and tourists alike. Yet today, Italian restaurants can be found in all corners of the city, and some of Boston’s oldest Italian restaurants have moved to or expanded their operations into the suburbs. Long-standing Boston classics, such as Santarpio’s and Pizzeria Regina, followed their Italian-American clientele and opened new branches in the suburbs north of Boston. Still, the North End carries a rich history, and Hanover Street remains a mecca of Italian food and culture, albeit one that has changed considerably from the days of red sauce and spaghetti.

–Kyle Stapleton, Henry Valentine, and Lila Zarrella

Works Cited

“Boston’s Foreign Restaurants.: French, Italian, German, Jewish and Chinese Bills of Fare–No Need to Go Around the World to Learn What Others Eat.” Boston Globe, January 7, 1894.

Cinotto, Simone. “Serving Ethnicity: Italian Restaurants, American Eaters, and the Making of an Ethnic Popular Culture.” In The Italian American Table: Food, Family, and Community in New York City, 180-209. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

O’Connell, James C. Dining Out in Boston: A Culinary History. Hanover: University Press of New England, 2016.

“Restaurant Life in Our ‘Little Italy,’ Where Bostonians and Aliens Mingle.” Boston Herald, February 21, 1904.

Thompson, Winifield M. “Behind the Scenes in an Italian Kitchen.” Boston Globe, April 29, 1906.

Vallandigham, E.N. “Boston Miniatures.” Boston Herald, November 30, 1911.