Workers’ housing on Second Street in South Boston, 1932. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library.

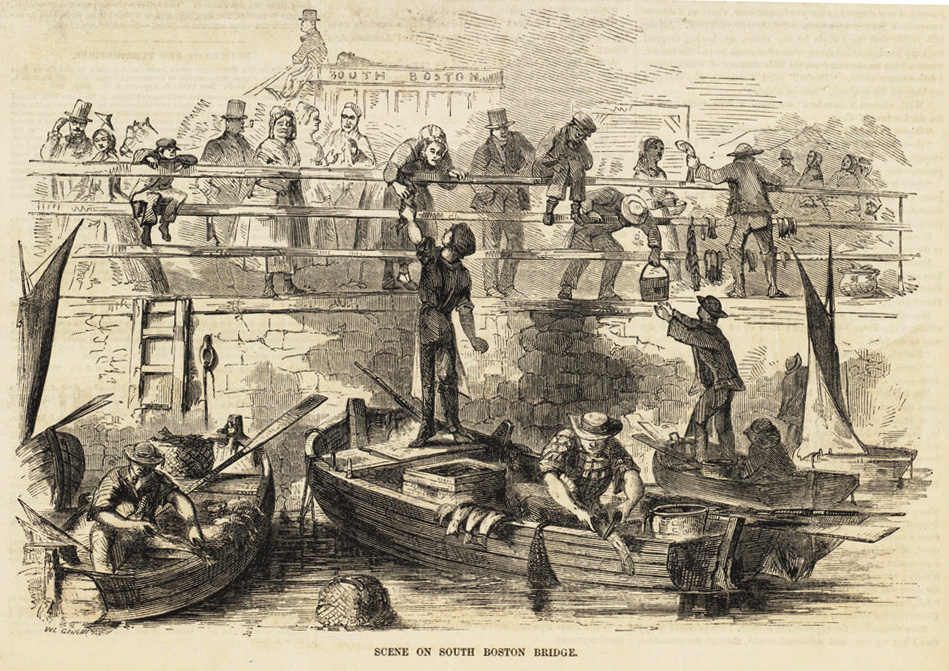

Settled by the Puritans in 1635, the peninsula known as Mattapannock or Dorchester Neck was used as a grazing area for much of the 17th and 18th centuries. After Boston annexed the area in 1804 and two bridges were built connecting it to the South End and downtown, the South Boston peninsula underwent rapid industrial development. As glassworks, chemical manufacturers, foundries, and machine shops sprung up in the lowland areas near the bridges, immigrant workers and their families moved across the channel to Southie’s lower end.

From the 1820s on, the Irish were the neighborhood’s dominant immigrant group. Many of the early settlers were skilled craftsmen and business owners, but with the onset of the potato famine in the 1840s, the Irish population surged. Impoverished newcomers settled mainly in the Lower End between A and F Streets, where they worked as laborers and dockworkers. The Irish population grew rapidly again after the Great Fire of 1872 swept through Boston’s Fort Hill neighborhood, driving some of the city’s poorest immigrant residents into South Boston.

The Archdiocese of Boston opened a spate of new Catholic churches to serve Southie’s burgeoning Irish communities. Outgrowing the small St. Augustine Chapel on Dorchester Street, Saints Peter and Paul Church opened on Broadway in 1845, followed by Gate of Heaven (1863), St. Vincent (1874), Our Lady of the Rosary (1884), St. Monica (1907), and St. Brigid (1908).

While Irish immigrants fueled most of South Boston’s growth in the nineteenth century, the neighborhood also attracted a large number of Canadians from the Maritime Provinces. A smaller group of German immigrants also settled there before and after the Civil War, finding work in the neighborhood’s breweries and bakeries. Other northern European groups began to arrive in the 1890s. A sizeable community of Polish immigrants settled around Andrew Square, founding Our Lady of Czestochowa Catholic Church in 1894. Lithuanian immigrants also settled in the Lower End around C and E Streets, where they too built a Catholic parish, St. Peter’s, in 1899. Moving out across the Dover Street Bridge from the South End, a small community of Russian Jews settled on Fourth Street and later opened a Hebrew school there. Further east, a small Italian settlement grew up along Third Street between H and L Streets. This infusion of new immigrants boosted Southie’s population to roughly 70,000 by World War I—more than double what it is today.

Although its population had diversified somewhat by the early twentieth century, the neighborhood maintained its Irish identity and continued to attract newcomers from Ireland. Alongside its churches, dozens of Irish social and charitable organizations flourished in Southie, including eleven chapters of the Ancient Order of Hibernians. Beginning in 1901, local residents convinced the city to host an Evacuation Day parade in South Boston to celebrate the British retreat from the area on March 17, 1776. The event evolved into a St. Patrick’s Day celebration and has continued to the present day.

South Boston remained largely Irish American long after other Boston neighborhoods in part because of its enviable location on the waterfront and its sizeable landmass. This allowed generations of Irish American families to move up from the crowded triple deckers of the Lower End to the more fashionable homes in City Point and other beachside districts. The long tenure of the Irish in South Boston gave its residents a particularly strong sense of place and a fierce determination to protect their turf from newcomers, especially African Americans. It was this defensive localism, combined with resentments of political decisions made by liberal suburban elites that helped make Southie the epicenter of the desegregation and busing crisis of the 1970s.

The racial animus and violence of that era deterred both African Americans and new immigrants from settling in the neighborhood in the 1970s and 1980s. As the foreign-born population grew across the city, in South Boston it dropped from 14 percent in 1960 to 7 percent in 1990. In the nineties, however, gentrification and the desegregation of the Old Colony and D Street public housing projects resulted in the first increase in foreign-born population in many years. By 2016, immigrants made up 14 percent of Southie’s population, with Dominicans, Chinese, and Albanians making up the largest groups. Still, the percentage of foreign-born residents continues to lag well behind the city as a whole and suggests that Southie’s days as a major immigrant gateway may not return any time soon.

Works Cited

Cullen, Kevin. “Change Comes to Southie.” Boston Globe, November 10, 1996.

O’Connor, Thomas H. South Boston, My Home Town. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1994.

Woods, Robert A. and Albert J. Kennedy. The Zone of Emergence: Observations of the Lower Middle and Upper Working Class Communities of Boston, 1905-1914. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1962, pp. 164-186.