Immigrant neighborhood in downtown Lynn, looking up Amity Street from Washington Street, ca 1900. Courtesy of Lynn Public Library.

Home to the Naumkeag native people, the area that would become Lynn was first settled by British colonists in 1629. Originally part of a larger region called Saugus, the town was renamed Lynn in 1637 and soon became a center of leather and shoe making. These industries, along with electrical manufacturing, would attract tens of thousands of immigrant settlers, making Lynn one of the most diverse and dynamic cities in Massachusetts.

Shoe City

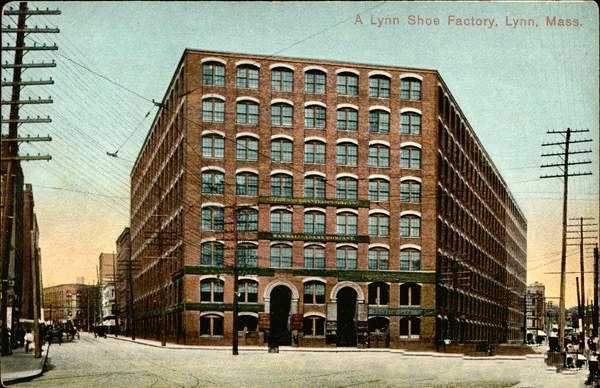

Although shoemaking began as a local artisan trade, it grew significantly with the American Revolution when the shoe market expanded across New England and beyond. At that time, most shoes were made in small family workshops known as ten-footers. As the industry grew, employers recruited seasonal workers from rural New England and in the 1860s began building large mechanized factories. By 1880, the city had more than 170 shoe factories, most of them clustered downtown.

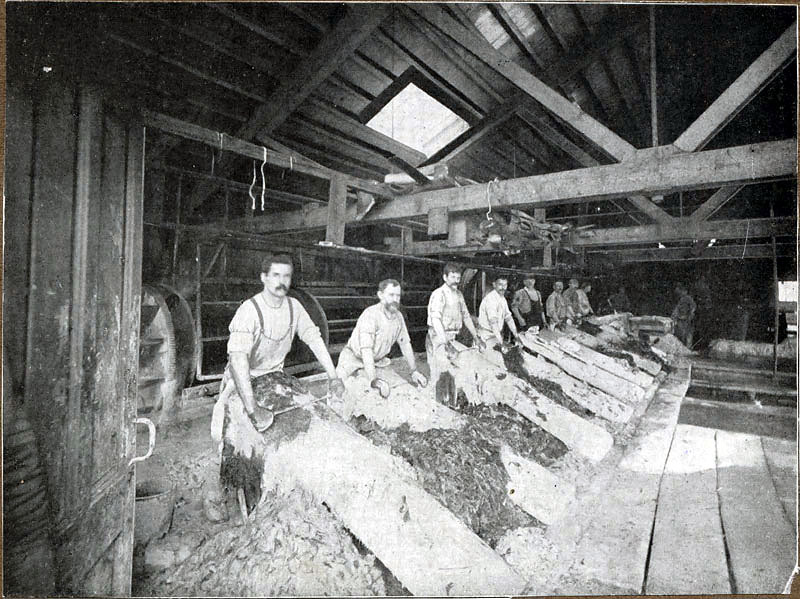

These factories employed some 10,000 workers, many of them unskilled or semiskilled. While the shoe industry continued to rely on rural native-born labor for much of the 19th century, it did attract a small stream of Irish and Canadian workers in the years before and after the Civil War. Immigrants made up an even larger proportion of the city’s leather workers who labored amid noxious chemicals and fumes in nearby tanneries.

By the twentieth century, Lynn had become the national leader in the production of women’s shoes, drawing thousands of new workers. While Irish and Canadian migration declined after 1910, new groups from Russia, Italy, Poland, Sweden, and Greece poured into the city. By the eve of World War I, roughly a third of Lynn’s population was foreign born. Many of the newcomers had been artisan shoemakers or needle workers in their home countries and brought traditions of union organizing that fortified Lynn’s strong labor movement.

Immigrant workers took up residence in downtown boarding houses and in homes within walking distance of the factories. The most populous immigrant quarter was the Brickyard, a working-class neighborhood just west of downtown. Many early Irish immigrants built homes there, but with the onslaught of new arrivals after 1900, houses were subdivided into tenements that housed multiple families. Local builders also erected hundreds of new three-deckers; between 1905 and 1913, more than 850 such apartment buildings popped up across the city, the majority in the Brickyard.

Different ethnic groups lived side-by-side but also clustered along certain streets. Russian Jews were prominent in the blocks around Blossom, Summer, and Pleasant Streets where they established synagogues, bakeries, kosher butchers and delicatessens. Over time, though, Jews and other immigrant groups moved out of the overcrowded Brickyard to West Lynn and the Highlands. Catholic immigrants tended to settle around the new ethnic parishes: French Canadians near St. Jean-Baptiste north of downtown and Poles in West Lynn near St. Michael. The Greek community clustered near St. George Orthodox Church in the Brickyard, while Swedes favored the Highrock area.

The mid-1920s proved to be a critical turning point for Lynn’s immigrant communities. Federal immigration restriction dramatically reduced migration just as the city’s shoe industry contracted. Dozens of shoe shops closed; others relocated to regions with lower taxes and labor costs. The depression of the 1930s accelerated the decline, and many of the downtown boarding houses and cafeterias closed. During these years, investment was redirected to the electrical industry and the General Electric plant in West Lynn. By 1930, the sprawling GE plant employed more Lynn workers than the shoe industry. Most were second generation, but smaller numbers of Italians, Poles, and Greeks continued to arrive in Lynn, as did a small stream of Black workers from Nova Scotia, the Caribbean, and the American South.

After the defense boom of World War II, and with the help of the GI Bill and low-interest veterans housing loans, the younger generation of white immigrant families began moving to the suburbs. Lynn’s population fell from a high of 102,320 in 1930 to only 78,471 in 1980—with the foreign-born share of the population dropping to only 9 percent. Local manufacturing continued to decline, and the downtown withered. In an attempt to stimulate new investment, the city used federal urban renewal funds to demolish much of the old Brickyard neighborhood in the 1960s. The project displaced many elderly immigrants but did little to spur development. Lynn’s economy continued to falter, and a torrential fire burned the last remaining shoe factory to the ground in 1981.

Immigration Since the 1960s

Despite its troubled economy, Lynn’s affordable housing and welcoming services continued to attract newcomers—particularly refugees. Beginning in the 1970s, the city’s older Jewish community helped sponsor Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union. Then in the eighties and nineties, more than two thousand Cambodian refugees and immigrants settled in Lynn. In the wake of the Vietnam war, Cambodians fled the killing fields of the Pol Pot regime, and many were drawn to a Buddhist temple founded in Lynn in 1984. Smaller numbers of refugees from Bosnia, Sudan, Somalia, Nepal, Bhutan, and other countries have also resettled in the city. They found support at the New American Center, founded in 2002 by earlier Russian emigres who joined with newer refugee groups to offer housing, employment, ESL, and other support services.

In recent decades, Lynn has drawn migrants from other regions as well. Latinos have figured prominently in this growth, dating back to the 1960s when newcomers from Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic first settled in the city. By 2010, Dominicans had become Lynn’s largest foreign-born group. Since the 1980s, Central Americans have further diversified the Latino population as they fled civil wars in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. Lynn’s Guatemalan community is now one of the largest in Massachusetts and includes a significant number of Mam Mayan-speaking indigenous people. Altogether, Latinos now make up more than 40 percent of the city’s population. Haitian immigrants and refugees from African countries have also increased the Black population, which now makes up around 14 percent of the city’s total.

While Lynn’s economy has not fully recovered from the decline of the shoe industry, the arrival of new immigrants has helped rejuvenate the city. After decades of decline, Lynn’s population has grown again as newcomers have taken up residence. The foreign born now make up a greater share of Lynn’s population than at any time in the past—with more than 40 languages spoken. Though they face many challenges, their small businesses and organizations have brought new vitality to downtown and to the old streets and neighborhoods where shoe workers once trod.

Works Cited

Cumbler, John T. Working-Class Community in Industrial America: Work, Leisure, and Struggle in Two Industrial cities, 1880-1930. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1979.

Dawley, Alan. Class and Community: The Industrial Revolution in Lynn. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976.

Glover, Kathryn. The Brickyard: The Life, Death, and Legend of an Urban Neighborhood. Lynn, MA: Lynn Museum and Historical Society, 2004.

Melder, Keith. Life and Times in Shoe City: The Shoe Workers of Lynn. Salem, MA: Essex Institute, 1979.

Pierce, Alan S. A History of Boston’s Jewish North Shore. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2009.

Rosenberg, Steven. “Russian Program a Casualty of Cuts,” Boston Globe, September 26, 2002.