Homes of immigrant families on Marginal Street, 1909. Courtesy Boston City Archives.

During the colonial era, the area that would become East Boston was comprised of five islands in Boston Harbor–Noddle’s, Apple, Governor’s, Bird, and Hog Islands. Samuel Maverick was the first European settler on Noddle’s Island in 1633, but it would be another two hundred years before major development and landfilling began. In 1833 General William Sumner founded the East Boston Trade Company, which began filling the swamps, building wharves, and developing a railroad freight terminal. In 1836, the city of Boston annexed East Boston–or Eastie, as locals later called it–and new industries sprung up, including a sugar refinery, an iron forgery, a timber company, and numerous shipbuilders.

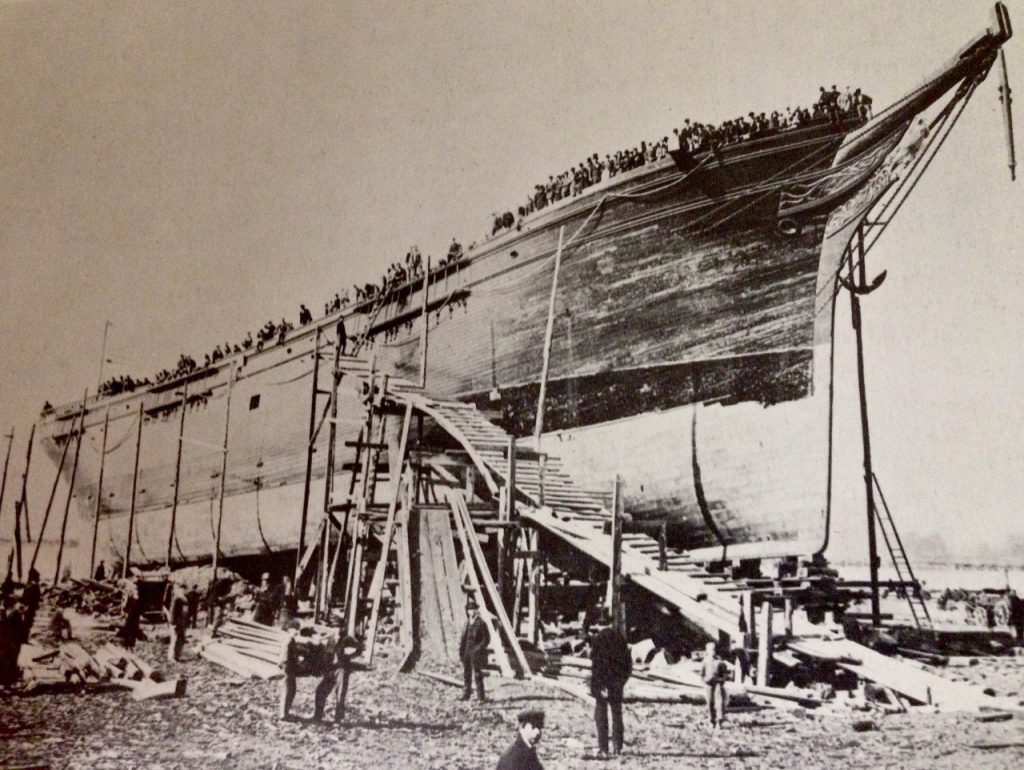

The best known of East Boston’s industrialists was Donald McKay, an immigrant from Nova Scotia who opened a shipyard on Border Street in 1845, Over the next forty years, McKay produced clipper ships that set speed records around the world. McKay hired skilled workers from Canada’s Maritime Provinces, Scotland, and Scandinavia. During the nineteenth century, in fact, East Boston had more Canadian-born residents than any other neighborhood in Boston. Growing from a community of roughly 1300 in 1855 to about 9000 by 1900, Canadians worked mainly in the shipyards or later as carpenters, machinists, pile drivers, and clerks.

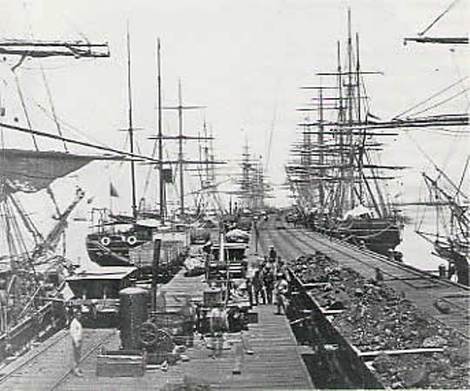

As in other parts of the city, the Irish made up the largest foreign-born group in East Boston. Irish migration surged with the Great Famine of the 1840s, and the Census recorded more than 3500 Irish-born residents in 1855. The majority worked as laborers who drained the swamps, built the wharves, and later moved goods on East Boston’s bustling waterfront. Until the 1880s, they lived mainly near the waterfront around Jeffries Point, Maverick Square, and Eagle Hill. Irish Catholics founded St. Nicholas Church—later renamed Most Holy Redeemer—in 1844. The church and its parochial school became the center of Irish Catholic life in East Boston and would remain the largest immigrant-serving parish for later ethnic groups.

With the completion of the first railroads to the mainland in 1875 and the first streetcar tunnel to downtown in 1901, East Boston became more closely connected to the rest of the city. And it soon became a convenient landing area for a new wave of immigrants from Russia, Italy, and Portugal. The neighborhood’s population thus grew from 36,930 in 1890 to 62,377 in 1915. The newcomers found work in the railroad docks, coal yards, machine shops, and candy, shoe, textile, and garment factories that replaced the old wooden shipbuilding industry. In the 1880s two settlements, Good Will House on Webster Street and Trinity House on Meridian Street, as well as the Immigrant’s Home on Marginal Way, were established to help the new arrivals. Moreover, the influx of newcomers created a need for new family housing, and hundreds of triple deckers were constructed beginning in the 1880s.

Jews from Russia and Eastern Europe were the first of these newer migrant groups to arrive in East Boston in the 1890s. Fleeing violent pogroms in the Russian empire and the crowded living conditions of the North and West Ends, Jews settled in the area north of Maverick Square and in Eagle Hill. By the early twentieth century, there was a thriving Jewish retail area of kosher markets, restaurants, and other businesses along Chelsea and Porter Streets. Several synagogues were located nearby, including the largest, Ohel Jacob, on the corner of Gove and Paris Streets. Jewish population peaked around World War I, with an estimated five thousand foreign-born residents. It was likely the largest Jewish community in Boston at the time.

During these same years, Italians also began settling in East Boston. Many came from the North End, but soon others arrived directly from Calabria and Sicily. In the early years of the twentieth century, they settled in Jeffries Point and in the blocks north of Maverick Square, while a smaller population of immigrants from northern Italy settled in Orient Heights. This Italian-born population more than doubled between 1910 and 1920, growing from 4565 to 10,151. Serving the religious needs of the growing Italian community, Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church on Gove Street opened in 1905, offering masses and other services in Italian.

After World War I, Italians and Italian Americans became the dominant ethnic group in East Boston and remained so until the late twentieth century. Eastie’s Irish, meanwhile, drifted north to Orient Heights and Winthrop while local Jews moved to Chelsea, Roxbury, Dorchester, and other rising Jewish communities. Noting the neighborhood’s role as a gateway for immigrant strivers who later moved on to higher income areas, settlement workers dubbed East Boston “a zone of emergence.”

East Boston’s population peaked in 1925, with over 64,000 residents. Immigration restriction in the 1920s, however, gradually reduced the migrant population thereafter. The East Boston Immigration Station, which opened in 1921, acted mainly as a screening and detention center for unauthorized immigrants and deportees. Eastie, meanwhile, became a largely Italian-American neighborhood, whose population began to decline after World War II. As Boston’s economy shifted from a manufacturing to a service-based economy, many local plants closed, including East Boston’s Maverick Mills in 1955, the Bethlehem Shipyards in 1983, and P&L Sportswear in 1986. Nevertheless, the growth of Logan Airport employed many of Eastie’s ethnic families, stimulating the economy but also prodding development that encroached on neighborhood space and quality of life.

The passage of the 1965 Immigration Act opened a new era of migration that later replenished Eastie’s population with a diverse new crop of immigrants. Beginning in the 1980s, a growing stream of Southeast Asians and Latin Americans began settling in the neighborhood. The largest groups came from Central America and Colombia, where civil wars, drug-related violence, and economic turmoil spurred many to leave. Others were refugees from the Vietnam War and the Cambodian genocide. As they settled among the older and declining white population, some of them found a hostile or even violent reception. Nevertheless, new arrivals continued to settle in Eastie in the 1990s and beyond, including newer groups from Mexico, Brazil, Peru, and Morocco.

Today, East Boston is an extremely diverse neighborhood with the highest percentage of foreign-born of any Boston neighborhood. Recently, housing costs have increased significantly as new luxury condominiums have been built along the waterfront, raising rents and forcing out many working-class immigrants. Throughout its history East Boston has endured numerous changes, but it has long acted as a home for immigrant strivers. It remains to be seen, however, whether East Boston will retain its reputation as a zone of emergence or if the impending gentrification will mark a new chapter for the neighborhood.

Research and writing for this profile was the work of students in Professor Marilynn Johnson’s Contested Cities Seminar in the History Department at Boston College in 2016. For more on the history of specific immigrant groups in East Boston, please see the links below.