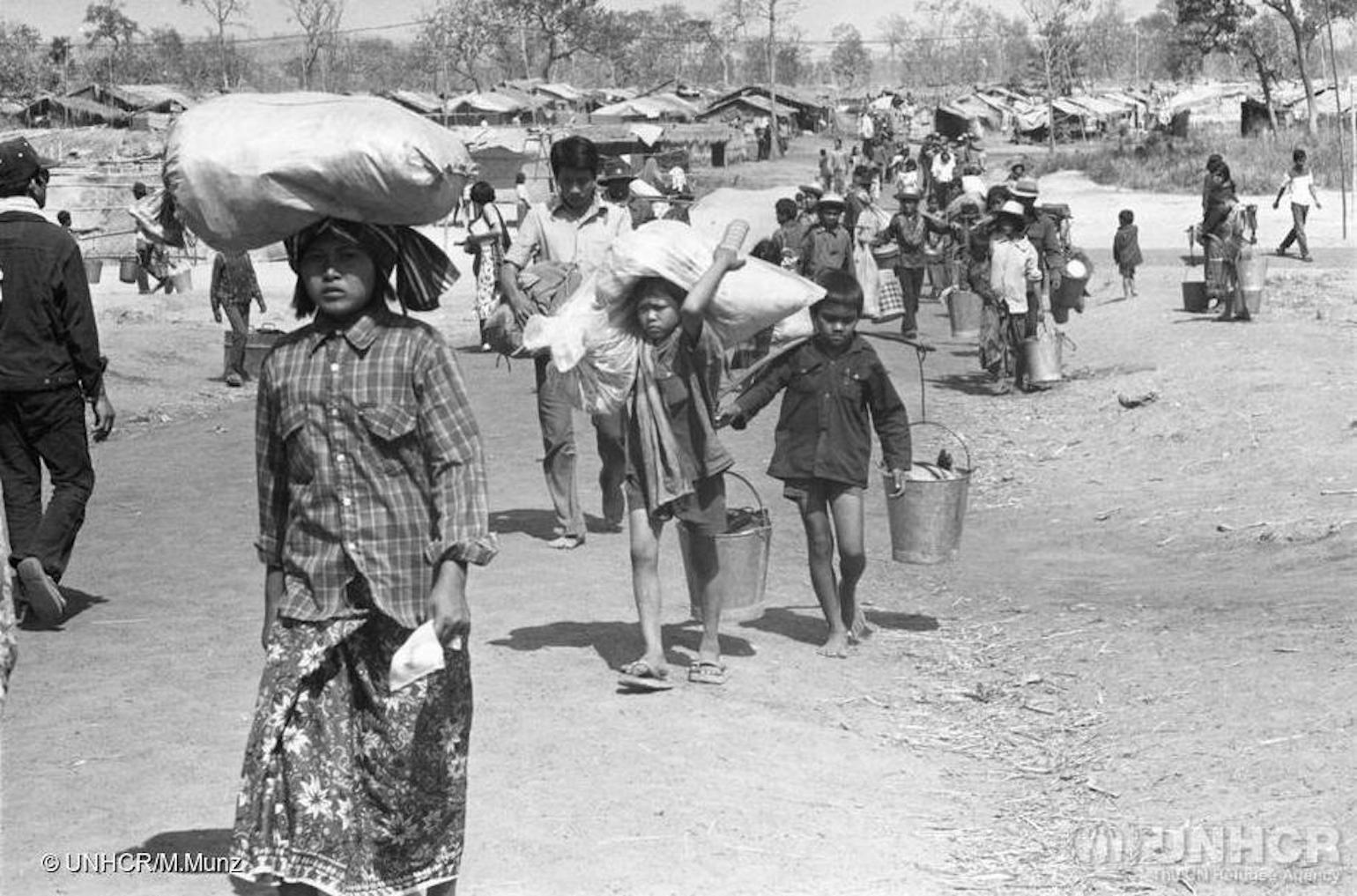

Cambodian refugees arriving in Khao I Dang camp in Thailand, 1980. In the years following the Vietnam war, thousands of Southeast Asian refugees resettled in greater Boston. Courtesy of UNCHR/M. Munz

Massachusetts has been home to refugees for more than four hundred years. Since the arrival of the Pilgrims fleeing religious persecution, oppressed people from across the globe have been seeking refuge in America. But the origins and treatment of refugees has changed significantly over time. Although the United States has embraced refugees as part of its democratic and humanitarian principles, its policies toward them have also been shaped by larger geopolitical concerns and a desire to advance America’s national interests.

What is a refugee? Prior to Refugee Act of 1980, the US had no official definition. It was generally understood that refugees were victims of political or religious persecution who fled their homeland and could not return. Yet before World War II, there were no explicit policies or laws relating to refugees. In the wake of the Nazi Holocaust, however, international and US efforts to protect refugees have grown, as has the diversity of refugee populations. But exactly who qualified as a refugee was often determined by the political and foreign policy issues of the day.

Prior to World War II, the largest refugee migrations to Boston involved Jews from Russia and Armenians from the Ottoman Empire. Between the 1880s and the 1920s, tens of thousands of Jews fled the Russian empire as violent pogroms, expulsions, and anti-Semitic laws targeted the Jewish population. New arrivals settled in the North and South Ends as well as in East Boston, often with help from the Boston branch of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) founded in 1904. Another mass exodus occurred from the Ottoman empire, where massacres in the 1890s and genocidal violence directed at Armenians during World War I killed more than a million people. Boston, Cambridge, and Watertown all hosted large refugee communities, and the latter became an important center of Armenian-American life.

World War II

The Second World War was a key turning point in the treatment of refugees, but one which came in the wake of a dismal failure to aid refugees in Europe. With the rise of Hitler and the Nazi party in 1933, anti-Semitic violence grew and several hundred thousand Jews emigrated over the next five years. Jewish organizations in the US, including the HIAS and the Boston Committee for Refugees, aided those fleeing the Nazis and lobbied the US government to admit them. But amid strong restrictionist sentiment, pervasive anti-Semitism, and high rates of unemployment during the Great Depression, Congress and President Franklin Roosevelt took little action, leaving many Jews to die in the concentration camps.

After the war, Jewish survivors along with millions of people left homeless by the conflict languished in refugee camps across Europe. Cooperating with the United Nations, the US and other countries worked to resettle these displaced persons. Congress authorized their entry under the Displaced Persons Acts of 1948 and 1950, the first US laws to explicitly address refugee admissions. Several thousand came to Boston in the late 1940s and 1950s.

A decade later, Massachusetts Senator John F. Kennedy co-sponsored the Azorean Refugee Acts in response to calls from Portuguese Americans in Massachusetts. The acts provided visas for five thousand Portuguese from the Azores after a devastating series of volcanic eruptions and earthquakes on the island of Faial. Many of the refugees moved to Massachusetts, including some who settled in East Cambridge and Somerville. The repeated need for short-term legislative solutions to refugee problems helped convince Congress to set aside ten thousand visas for refugees under the 1965 Immigration Act.

The Cold War Years

During these years, the politics of the Cold War deeply influenced refugee policy and admissions. From the 1950s to the 1980s, refugees from the USSR and other Communist countries made up the vast majority of those admitted to the US. America welcomed these expatriates as a humanitarian act but also as a way of condemning Soviet aggression and the failures of Communism.

The US resettled these newcomers by partnering with local voluntary agencies in Boston such as the International Institute, the International Rescue Committee, Catholic Charities, and the Lutheran Refugee and Immigration Service. With government support and funding, they found housing for refugees in affordable neighborhoods and paired them with local sponsors to help them find jobs and needed services. Many of those refugees would in turn sponsor other family members, thus building the foundations of new immigrant communities. Places like Dorchester, Jamaica Plain, Lynn, and Revere have all hosted such refugee-spawned communities.

Small numbers of Eastern European refugees arrived in Boston in the fifties, but the most visible new group were those fleeing the Cuban revolution of 1959. Coming in several waves between 1959 and 1973, anti-Communist Cuban exiles received extensive resettlement funds and services from the US government and were assisted locally by Catholic Charities and local parishes. Most of the early refugees were white and affluent, and many bought homes and opened businesses, especially in Jamaica Plain and Allston-Brighton—home of the city’s largest Cuban communities.

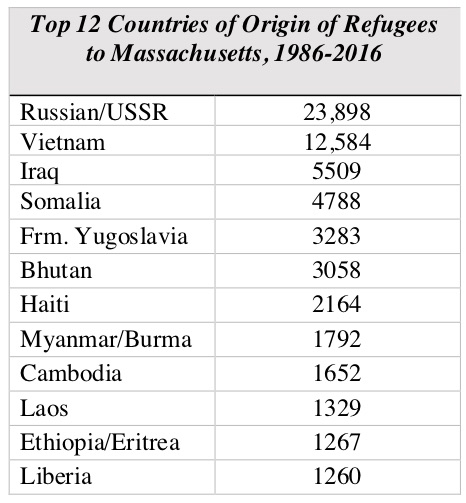

An even larger group of refugees came to Massachusetts from the Soviet Union, beginning with a trickle of arrivals in the 1970s to more than a thousand a year from 1988 to 1998. Mainly Jews facing discrimination and repression under the Soviet regime, many lost their jobs, were barred from universities, and denied the right to emigrate. Jewish advocacy groups such as HIAS and Action for Soviet Jewry relentlessly lobbied local and national officials to pressure the Soviets to release them. With the lifting of travel restrictions in 1989 and the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, a mass emigration ensued. Between 1986-2016, more than 23,000 refugees from the Soviet Union or Russia came to Massachusetts, more than any other national group. Settling mainly in the greater Boston area, the refugees were aided by an impressive network of Jewish organizations and synagogues, and many settled in suburbs with established Jewish communities.

Also arriving in this period were large numbers of refugees from the Vietnam War. Given America’s central role in the conflict, the US took responsibility for the postwar refugee crisis, bringing more than a million refugees from Southeast Asia. Greater Boston was one of the top ten resettlement areas, especially for Vietnamese and Cambodians. Vietnamese began arriving in small numbers with the end of the war in 1975 and then came in much greater numbers in the late seventies and eighties. While initially resettled across the region, Dorchester’s Fields Corner neighborhood emerged as the center of the Vietnamese refugee community. Cambodians were placed in Boston, Revere, and Lynn, but they increasingly gravitated north to Lowell. Both groups have since developed thriving ethnic enclaves, religious centers, and refugee organizations across the region.

Growing concerns for human rights helped fuel these resettlement efforts and also spurred the passage of the 1980 Refugee Act. The act defined refugees broadly as victims of persecution (not just Communist persecution), raised the annual ceilings for refugee admittance, reserved spots for asylees (those who applied for protection after entering the US), and expanded resettlement programs. But not all refugees seemed to qualify. Under the Reagan administration of the 1980s, those fleeing violence in Haiti and Central America—countries whose leaders were aligned with the US—were still turned away. Some Haitians successfully claimed refugee status beginning in the 1990s, but appeals by Central Americans fleeing gang violence have often been denied.

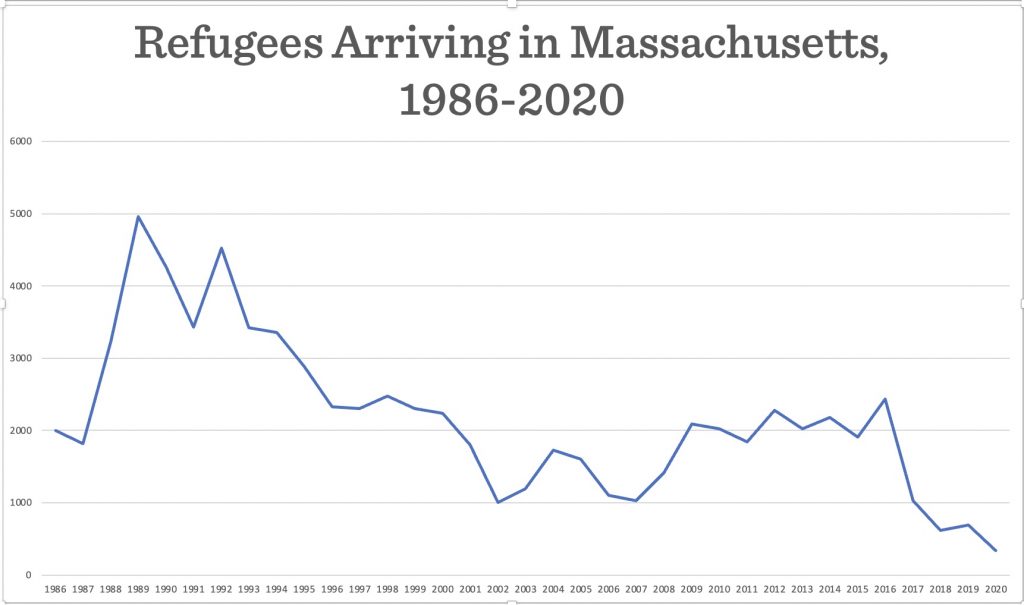

The End of the Cold War and 9/11

With the end of the Cold War, refugee admissions began to decline in the 1990s. Those who did qualify came from a larger number of countries, many of them riven by new forces of ethnic nationalism and religious conflict that grew in the aftermath of the Cold War. In Boston, new arrivals from the Balkans came to escape the wars and ethnic cleansing unleashed by the breakup of Yugoslavia. Political instability and tribal tensions also grew in Africa, and a growing number of refugees came to Boston from Somalia, Liberia, Ethiopia, and Central Africa.

The terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center on 9/11 stoked widespread public fear and growing anti-Muslim sentiment as well as bringing a severe reduction in refugee admissions. Soon, however, the prolonged fighting and devastation of the US-led war in Iraq brought more than five thousand Iraqis to Massachusetts. At the same time, ethnic and religious repression in Bhutan and Myanmar likewise sent a stream of Lhotshampas (ethnic Nepalis from Bhutan) and Rohingya (a Muslim minority group in Myanmar) to the Boston area. Beginning in 2011, a civil war in Syria also brought several hundred displaced Syrians to the state.

Unlike the earlier refugees, however, recent newcomers are more likely to be resettled in other parts of the state. High rents and a tight housing market have made Boston a less suitable place for refugees to start a new life.

President Donald Trump’s bans on travel from several majority Muslim countries severely limited those refugees’ ability to enter the US after 2016, while his administration reduced the overall number of refugee admissions. And beginning in 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic –accompanied by border closures and a sharp decline in global air travel–produced unprecedented low levels of immigrant and refugee arrivals. Migration slowly resumed in mid-2021, but stricter policies governing the admittance of those seeking asylum created a vast backlog of cases. Although President Joseph Biden attempted retain the policy of requiring asylees to apply for asylum prior to entering the US, a federal judge rejected it in 2023. Since then, refugee and asylee entries have swelled, creating challenges for many city and state leaders to aid and house the new arrivals.