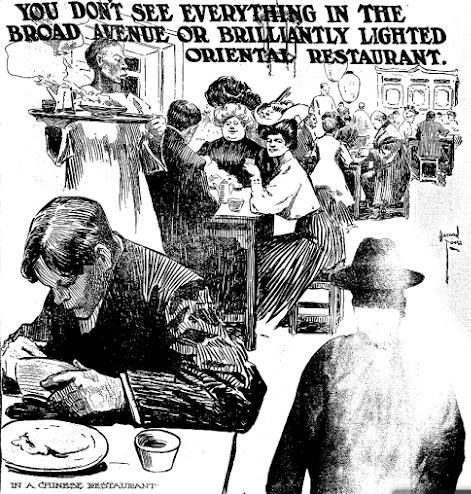

Unidentified man seated at the Oriental Restaurant at 32 Harrison Street owned by Bun Fong Low Company, ca. 1895-1910. Courtesy of the Trustees of Boston Public Library.

Chinese restaurants in Boston were strikingly successful in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—especially given the city’s small Chinese population at the time. But they were also subject to white racism, harassment, and violence that harmed their business and made it more dangerous. Ultimately, though, by offering tasty food and diversifying the cuisine to accommodate American tastes, Chinese restaurant owners succeeded in building prosperous and influential businesses in Chinatown and beyond.

Chinese restaurants in Boston were strikingly successful in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—especially given the city’s small Chinese population at the time. But they were also subject to white racism, harassment, and violence that harmed their business and made it more dangerous. Ultimately, though, by offering tasty food and diversifying the cuisine to accommodate American tastes, Chinese restaurant owners succeeded in building prosperous and influential businesses in Chinatown and beyond.

Early Views of Chinese Restaurants in Boston

Boston’s Chinatown dates back to the mid 1870s when Chinese migrants from western states settled along Harrison Avenue between Essex and Beach streets. It appears that the first Chinese restaurants in Boston opened in the early-to-mid 1880s on Harrison Avenue. Usually located on the second or third floors, these eateries featured adjacent areas for lodging and gambling. They served the Chinese population in Boston, mainly immigrant working men from Guangdong province in southern China. Meals included lots of rice and fresh vegetables, fish, chicken or pork, along with fried noodles and oolong tea. Such restaurants were unknown to most white Bostonians and did not appear in the city business directory until 1896. For this reason, there are no Chinese restaurants that appear on our 1895 map.

Most white Bostonians at the time refused to visit Chinese restaurants, viewing the food as a degraded product of an “ inferior race.” In an 1885 article published in the Boston Globe, Chinese writer and activist, Wong Chin Foo noted that “the average American when he first approaches the Chinese table does so in fear and trembling.” Racial animus strongly influenced American attitudes toward immigrant cultures, and decades of virulent anti-Chinese racism gave rise to negative stereotypes and outlandish claims about Chinese food and those who prepared it.

Most prominently, white Americans perpetuated the myth that Chinese restaurants served such delicacies as “cat cutlet, griddled rats, dog soup, roast dog, and dog pie” as portrayed in an 1854 fictional menu published by the Boston Investigator. Many claims about Chinese restaurants serving “vermin” highlighted a common view that Chinese restaurants and thus, Chinese people were unsanitary, dirty, and uncivilized. An 1894 Boston Globe piece commented on these supposed unsanitary conditions, noting that Chinatown was viewed as “the breeding nest of disease”–hardly a selling point for those seeking good food.

Bohemians and Chinatown Slumming

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, however, some white Americans became attracted to Chinatown because of its vice and “exoticism.” Influenced by colonialist ideas of the Chinese as exotic others, white slummers and Bohemians sought out the restaurants and dives of Chinatown for their evening adventures. Chinese restaurants were a prominent focus of these excursions, since they were conspicuous and far less controversial than other Chinatown attractions such as gambling and opium dens.

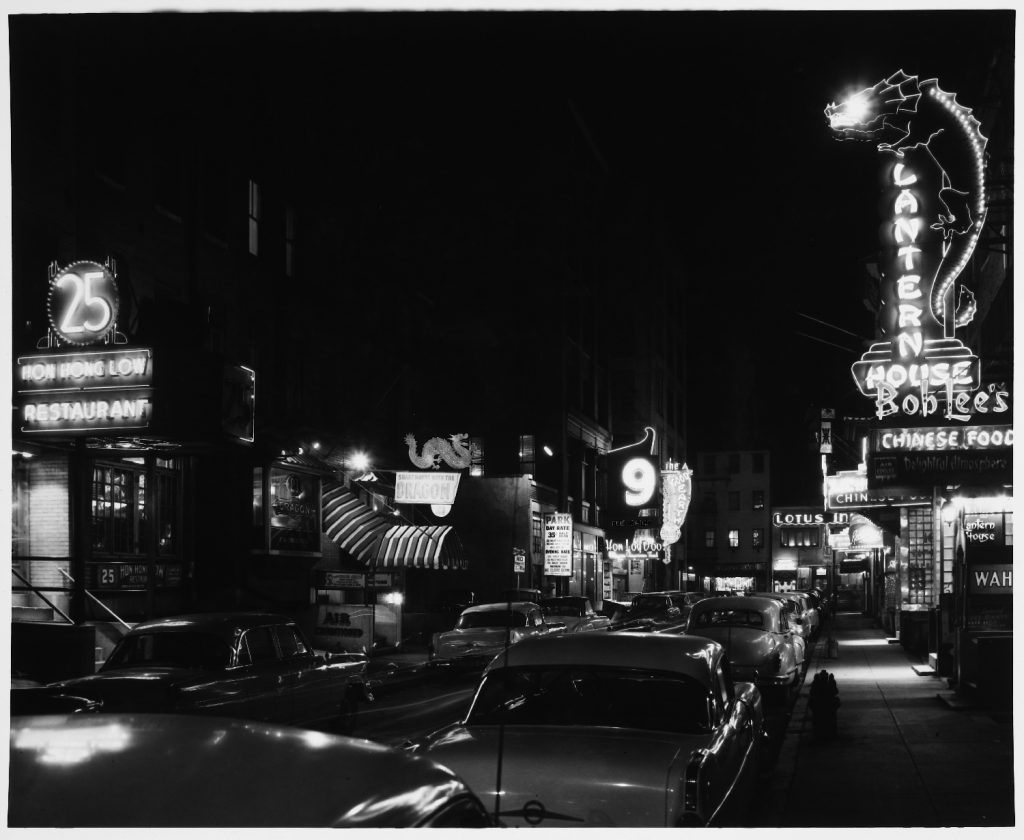

In 1899 the Boston Globe reported that a party of “beautiful society ladies” and “brave society men,” including the Lieutenant Governor, went “slumming” in Boston’s Chinatown. By the 1910s, the practice of slumming was common and many white Americans would pay for tours of Chinese neighborhoods. Because of the area’s proximity to the theater district, cabaret and big-band style Chinese nightclubs and restaurants proliferated across the neighborhood during the 1920s and after.

The growing popularity of Chinese restaurants is evident on our 1926 map, which shows a cluster of ten restaurants in Chinatown but also a growing number in the South End and even a few as far out as Charlestown, Brighton, and Dorchester. These restaurants, compiled from the city directory, were just a portion of the total number. As the Boston Herald put it in 1919, “Chinatown has become respectable. More than that, Chinatown has invaded the domain of respectability.”

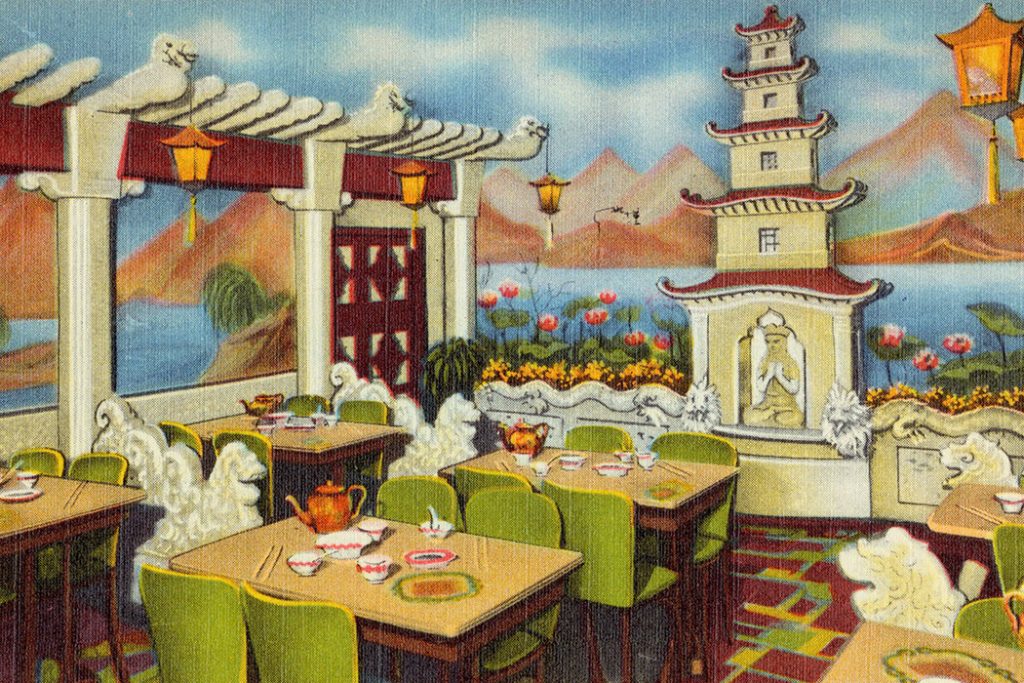

Some of the success of Chinese restaurants in this period can be attributed to owners who capitalized on the orientalist craze through the decor and ambience of their restaurants. Proprietors often played up ‘Oriental’ associations through the use of gaudy lanterns, wall hangings with Chinese dragons and calligraphy, and bright red and gold color schemes. As early as 1894, a Boston Globe article noted such decor in a Chinatown restaurant, describing “banners of oriental subject… two fine lanterns,” along with “a broad silken border of deep crimson edged with gold.” The writer characterized these features “as being odd, mysterious–almost awesome.” Such appeals to white customers’ fascination with the “Far East” were carefully cultivated by popular restaurants such as Ruby Foo’s Den in the 1920s and 1930s. Moreover, some of these Chinatown restaurants stayed open until midnight or later, attracting a late night crowd from the nearby theater district.

Chop Suey

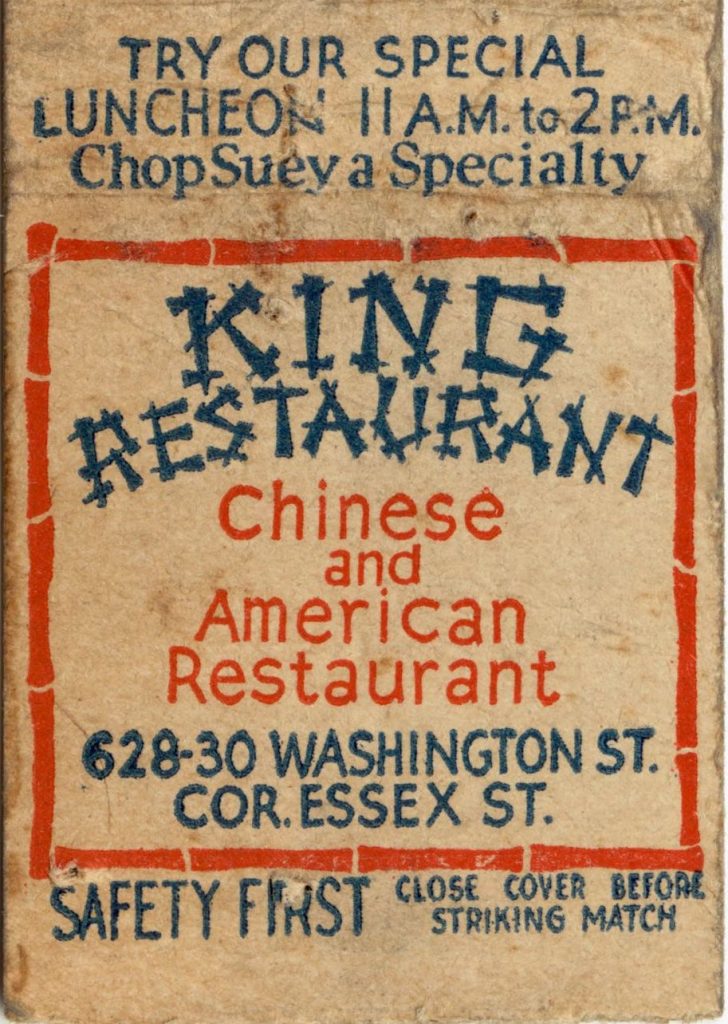

Even more important in the growing popularity of Chinese restaurants was the rise of hybrid Chinese American foods like “chop suey.” Chop suey does not refer to a single dish or recipe, but was rather a common method of cooking a mixture of chopped meat and vegetables–what the Chinese called “bits and pieces”–served in a sauce. While the origins of chop suey are hotly debated, it quickly became the most popular Chinese American dish, especially in New York and Boston. Soon Chinese restaurants began to rebrand themselves as “chop suey joints” and focused on appealing to non-Asian customers through menus in both English and Chinese.

Over time, other Chinese American dishes joined chop suey on these menus. Egg foo young, chow mein, and egg rolls became popular fare at Chinatown restaurants by the mid-20th century. Chefs also incorporated local ingredients into their dishes. One striking example is lobster sauce, a sauce made with a base of broth and herbs and served with lobster or shrimp. Unlike in other cities, however, lobster sauce in Boston took on a dark brown color and sweetness as chefs added molasses to the recipe. As a historic center of the sugar trade with the Caribbean, Boston produced a vast amount of molasses, which found its way into local Chinese cuisine.

Restaurants and Immigration Laws

The proliferation of Chinese restaurants in the early 20th century occurred at a time when the population of Boston’s Chinatown’s remained flat–or even declined–because of the Chinese Exclusion Act. This law, first passed in 1882, barred the entry of Chinese workers except for merchants, diplomats, and students. Some Chinese restaurant owners, however, used their merchant status in order to circumvent immigration restrictions at the time. After 1915, investors in “high grade” restaurants could gain a working visa that allowed them to return to China and bring employees with them back to the US. In order to meet these requirements, Chinese immigrants often would pool their resources to open “luxury chop suey” restaurants and then take turns running the business to reach merchant status. The investors would bring relatives to work in the restaurant who would then train and save to become investors themselves and start the cycle again.

At least four Chinese restaurants on our 1926 map show ownership by groups of three to six immigrant proprietors. Historian Heather Lee notes that from 1910 to 1930, the number of Chinese restaurants in the United States quadrupled as groups of immigrants began running and owning restaurants instead of laundries or other businesses. This practice likely fueled the Boston restaurant industry as well.

Although some Chinese owners managed to work around the immigration restrictions to build successful restaurants, they continued to face hostile publicity, harassment, and even violence. In fact, the most common references to Chinatown or Chinese restaurants in Boston newspapers at the time were those describing criminal activity. Boston Globe headlines such as “Fight in Chinese Restaurant” (September 7, 1901) and “Thugs Beat Chinese at Restaurant Here” (October 10, 1928) often noted the connection to Chinese restaurants in the title, even though most of these stories were about non-Chinese people committing acts of violence against restaurant owners or patrons. Nevertheless, Chinese restaurants were viewed as places of crime and loose morals where unmarried white women could be lured into depravity. In response, state Representative John L. Donovan proposed a bill in 1910 to prohibit unescorted women under 21 from entering a Chinese restaurant. Ultimately, the bill was declared unconstitutional by the Attorney General and never went into law, but it illustrates the fears many white Americans held about Chinatown and its residents.

Legacies and Changes

Although immigrant men owned nearly all of the first generation of Chinese restaurants in Boston, Chinese women became a growing presence in the industry beginning in the 1920s. One of the first and most famous women proprietors was American-born Ruby Foo, owner of Ruby Foo’s Den. Opening her first restaurant at 6 Hudson Street in Boston in 1929, Foo later opened locations in Miami, New York, Washington DC, and Providence. Foo’s “Den” garnered acclaim not only for its food, but also for the theatrical aspects of the dining experience, with major sports figures and celebrities among the patrons. In later years, the Boston area was home to several other prominent women-owned Chinese restaurants, including those run by Anita Chue, Mary Yik, and Joyce Chen.

The end of Chinese exclusion in 1943 and other changes in immigration laws led to a dramatic transformation in Chinese cuisine in America after 1970. Most prominently, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, along with relaxed emigration controls by the Peoples’ Republic of China in 1978, allowed thousands of Chinese immigrants from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and other regions across mainland China to come to the United States. Soon, Cantonese cuisine and Americanized Chinese foods like chop suey and chow mein began to fall out of fashion. Different regional cuisines took their place with an emphasis on authentic ingredients and preparations. Today, this diversity of flavor and proliferation of Chinese and Asian-fusion restaurants reveals a more varied and innovative culinary landscape. In Boston, as in many US cities, Chinese cuisine has become the most popular “ethnic” option and one that has changed the way Americans eat.

–Mikayla Sanchez, Ling Han Su, Stephanie Wang, and Lila Zarrella

Works Cited

Auffrey, Richard. “The First Restaurants In Boston’s Chinatown (Part 1-Expanded/ Revised).” The Passionate Foodie (blog), February 28, 2020. See also list of other blog entries at bottom of this post.

“Boston’s Foreign Restaurants.: French, Italian, German, Jewish and Chinese Bills of Fare–No Need to Go Around the World to Learn What Others Eat.” Boston Globe, January 7, 1894.

“Made Tour of Resorts.: Lieutenant Governor Crane Visited the North and South Ends,” Boston Globe, January 25, 1899.

Chen, Yong. Chop Suey, USA: The Story of Chinese Food in America. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

Coe, Andrew. Chop Suey: A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

“Restaurant Bill Killed,” Boston Herald, April 23,1910.

“Ruby Foo, 42, Restaurateur, Dies Suddenly.” Boston Globe, March 16, 1950.

Erby, Kelly. Restaurant Republic: The Rise of Public Dining in Boston. University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Godoy, Maria. “Lo Mein Loophole: How U.S. Immigration Law Fueled A Chinese Restaurant Boom.” NPR, February 22, 2016, sec. Food History & Culture.

Liu, Michael. Forever Struggle: Activism, Identity, & Survival in Boston’s Chinatown, 1880-2018. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2020.

“Regenerated Chinatown Has Invaded Respectability.” Boston Herald, February 23, 1919.

Singh, Maanvi. “Boston Chinese: A Fusion Food Cooked Up in a Melting Pot City.” GBH News, March 30, 2016.

Wong Chin Foo. “Chinese Cooking: An Interesting View into a Chinese Restaurant.” Boston Globe, July 19, 1885.