Boston Caribbean Carnival in 2007. Courtesy of BostonCarnival.com.

Because of its maritime location and historical connections to the Caribbean and the slave trade, Boston has been home to black West Indians since colonial times. Voluntary migration to the city began in the late nineteenth century, but it was not until the 1910s that a more permanent West Indian community emerged. Their numbers would increase to roughly five thousand by the early 1950s, or roughly 12 percent of the city’s black population.

During these years, immigrants came mainly from the islands of Jamaica, Barbados, and Montserrat. West Indians came to rely on migration as a survival strategy amid longterm structural problems in the British island economies, including over-reliance on single cash crops, exploitative foreign commercial activities, and an underdeveloped manufacturing sector. Perpetually low wages and high unemployment drove many Jamaican and Barbadian men to seek work building the Panama Canal in the early twentieth century, and many later used their earnings to subsidize family members’ migration to the US. Seeking greater economic stability, West Indian newcomers also came north in search of better educational opportunities for their children.

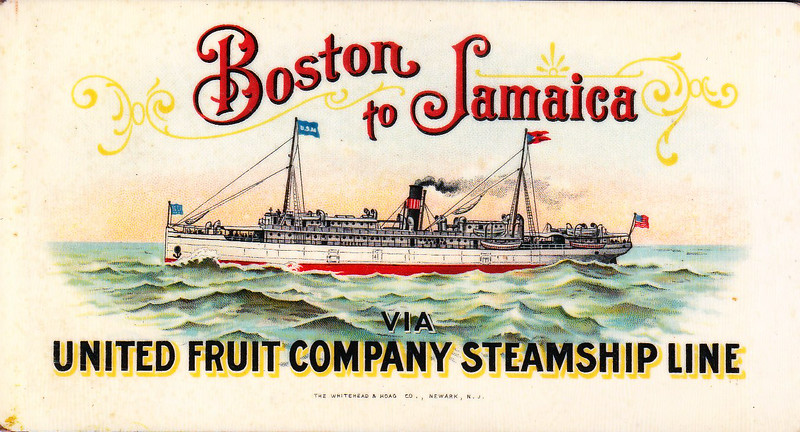

But perhaps the most important reason that West Indians ended up in Massachusetts was the United Fruit Company’s direct steamer service from Boston to Kingston and Port Antonio, Jamaica. Headquartered in Boston from 1899 to 1938, the United Fruit Company (a predecessor of Chiquita) was one of the world’s largest banana and tropical fruit producers. By 1920 more than eighty West Indians were arriving in Boston per year via United Fruit’s Great White Fleet, either as ticketed passengers or as workers who stowed away or jumped ship.

Immigration dropped off precipitously after passage of the McCarran Walter Act in 1952, which assigned restrictive quotas to colonies in the western hemisphere. After 1965, however, the ceilings were raised, and many Jamaicans and Barbadians made use of family reunification provisions to reunite with relatives in the Boston area. In the 1990s, sizeable new migrant groups also began arriving from Trinidad and Tobago, the Bahamas, Grenada, Dominica, and St. Vincent. This new wave has also included more highly educated professionals, whose skills have helped them secure H-1 work visas.

Settlement

West Indians settled largely within or near existing African American communities in Boston, reflecting the role of racism and segregation in shaping the choices of black immigrants. In the early twentieth century, they settled mainly in the Crosstown area of the South End (around Massachusetts Avenue) and in the historically black sections of Cambridgeport. By the late 1930s, some West Indian families—along with African Americans—were moving south into Roxbury as Jewish families moved out.

The diffusion of West Indian settlement accelerated after 1968 when the Boston Banks Urban Renewal Group agreed to end racially discriminatory lending practices across a swath of Roxbury, Dorchester and northern Mattapan. With mortgages now more readily available, West Indian families were among the first to purchase homes in these formerly white (and mainly Jewish) neighborhoods along Blue Hill Avenue. By the 1980s, these areas became predominantly black, with visible concentrations of new immigrants from Haiti and the West Indies. A smaller percentage of West Indians have also moved to the suburbs, mainly to Randolph, Malden, and Brockton.

Work

In the early twentieth century, most West Indian newcomers—whatever their education or skills—were limited to employment as laborers, service, or domestic workers. Most men worked loading freight on the docks or railroads, or as janitors or porters. West Indian women found work primarily as domestics. For many of these newcomers, who were among the most educated and driven in their home islands, such jobs provided higher wages but were clearly a step down in status.

For the new wave of immigrants arriving since the 1960s, service work has become even more important. West Indian women continue to find work in childcare but have also moved into the burgeoning healthcare industry, from nurses’ aids to hospital administrators. Increasingly, West Indians and their children have been accessing higher education and pursuing careers in professional fields such as teaching, nursing, business, and civil service. Although their mean incomes surpass those of native-born blacks, they continue to lag behind those of native-born whites.

Sources and Further Reading

Violet Showers Johnson, The Other Black Bostonians: West Indians in Boston, 1900-1950 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006).