Frank Storer plays piano to a crowded dance hall at the Intercolonial Club on Dudley Street in the 1950s. It was one of at least five dance halls that featured live music by Irish and Canadian bands in the mid-20th century. Courtesy of Frank Storer.

Immigrants have long shaped Boston’s music scene, and perhaps no tradition has been as enduring as that of the Celtic bands that once filled dancehalls along Dudley Street in Roxbury. For more than forty years–from the 1920s to the 1960s–Irish, Scottish, and Acadian fiddling bands played to large crowds of immigrants from Ireland and the Canadian Maritime provinces. As a transit hub for the elevated train and streetcar lines, Dudley Square became a magnet for immigrant musicians and fans, a place where traditional Celtic music met new American styles and practices.

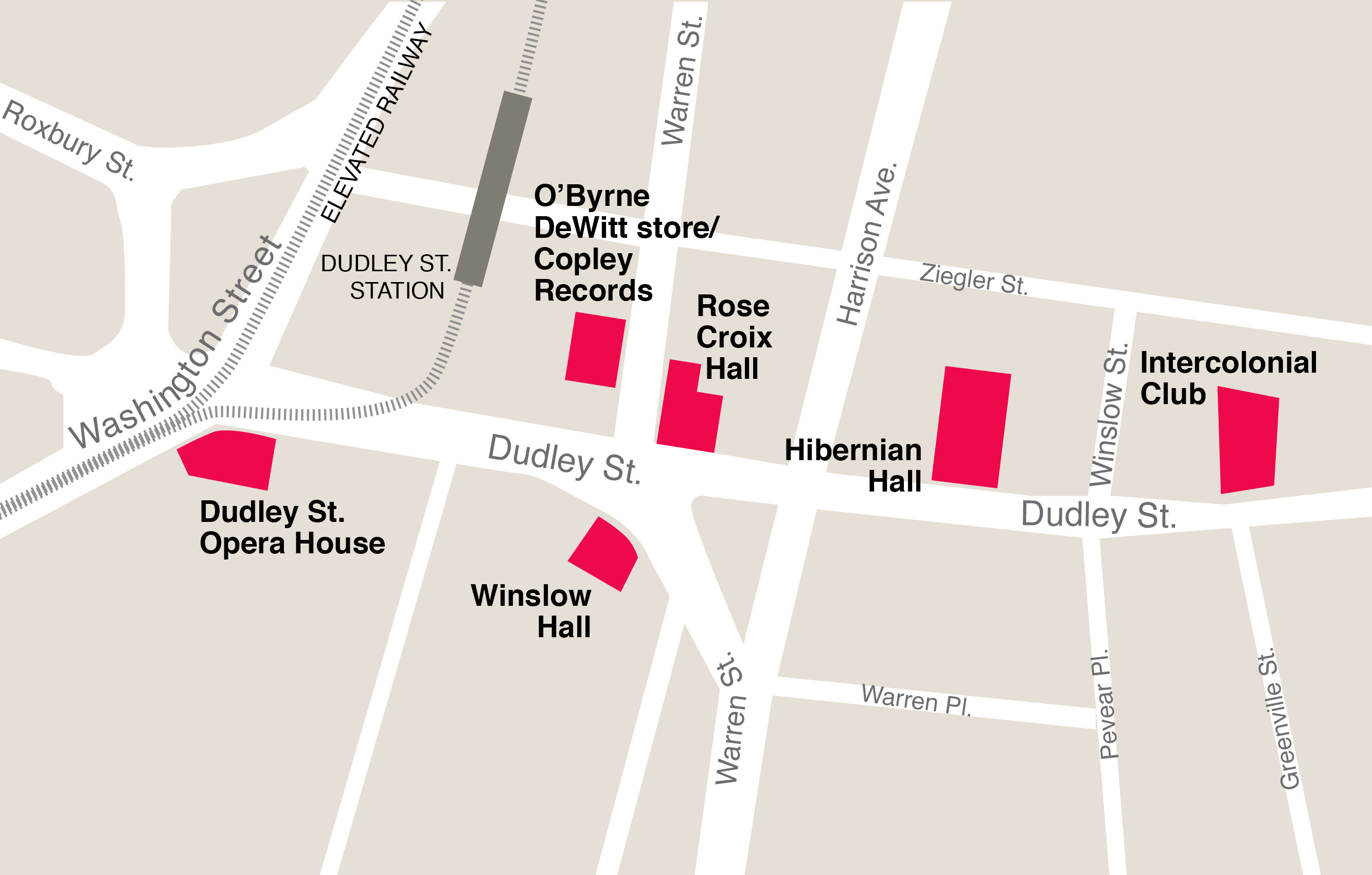

Irish and Canadian immigrants first brought Celtic music to Boston in the mid-19th century, hosting dances and house parties in their neighborhoods. In the early twentieth century, dancehalls in the South End featured Irish and Canadian bands, but in the 1920s, the scene shifted out to Roxbury, where new transit lines were bringing growing numbers of immigrants and their children. Around Dudley and Warren Streets, Irish and Canadian newcomers erected buildings for their fraternal orders, with large meeting halls on the upper floors. Hibernian Hall was run by the Ancient Order of Hibernians, while Canadians operated the Intercolonial Club and the Knights of Columbus’ Rose Croix Hall. Other popular venues were Winslow Hall and the Dudley Street Opera House.

Soon enterprising migrants started booking local fiddle bands to play dances there on Thursday and Saturday nights. Canadian bands were especially popular in the twenties and thirties, including groups led by Scottish-style Cape Breton fiddlers Johnnie Archie MacDonald and Alec Gillis, leader of the Inverness Serenaders. Other groups hailed from Prince Edward Island or featured Acadian fiddlers from Nova Scotia, such as Tommy Doucet and Alcide Aucoin. Irish fiddling bands were also popular, particularly at Hibernian Hall, Winslow Hall, and the Dudley Street Opera House. Fan favorites included the Emerald Island Orchestra led by Tom Senier, Dan Sullivan’s Shamrock Band, and Joe O’Leary’s Irish Minstrels.

Most bands played a mixture of traditional Celtic music (such as reels, jigs, and hornpipes) and popular American styles (such as waltzes and foxtrots). The five big Roxbury dance halls featured groups with different regional styles who attracted fans from back home, but there was also a good bit of cross-fertilization between these Irish, Scottish, and French-style players.

Their formula was a success, as thousands of fans flocked to dancehalls for both music and companionship. As one patron recalled, “You were always meeting somebody from home…. You’d go up to a dance, and if you didn’t know anybody… you’d leave it and go to another.” Mainly young and single, many of the fans worked in local factories, shipyards, and transit lines, giving them spending money for weekend entertainment. Many of the women were employed as domestics and looked forward to their night out, typically on Thursdays. Those weeknight dances were very popular. As one promoter, Ralph MacGillvray, remembers, people teased him that he was “running a marriage bureau down there… You’d get four or five or six hundred girls–they’d come in groups. They’d be ready when the first dance was on, and they’d stay till the last.” Many musicians and fans did in fact meet their future spouses at the dancehalls.

The end of Prohibition saw new pubs and restaurants open along Dudley Street in the 1930s, adding to the local nightlife. But for many who were unemployed during the Depression, the door fees to the dances were no longer affordable. Instead, people organized house parties, or “kitchen rackets,” a tradition of home-based entertainment brought over from rural Ireland and the Maritimes. These were common during the Depression, Billy MacGillvray recalled, for people who were “up against it, and they’d have a kitchen racket and raise a few bucks.” Musicians played in the kitchen, where the linoleum served as a dance floor. More elaborate gatherings might happen in the summer, when local domestics cared for the homes of wealthy residents. “They’d usually have a big basement–a big room, big as this house, and a tile floor. We’d have a party, invite fellas and girls and we’d dance,” said MacGillvray. “Whether the owners–who were away in Europe and so on–whether they knew or not, nobody gave a damn.”

World War II boosted the economy and helped bring patrons back to the Roxbury dancehalls. But the biggest change came after the 1945, when bad harvests and postwar economic woes in Ireland sent a surge of new immigrants to Boston. A new generation of Irish bands—many from the western counties of Galway, Connemara, Clare, Kerry, and Sligo—took the stage at the Intercolonial and other Dudley Street halls. Some of the most popular figures were accordionists: Johnny Powell and His Irish Band, who were mainstays at the Intercolonial Ballroom, and Joe Derrane and his All-Star Ceílí Band, a group led by an Irish American band leader from Mission Hill.

Like their Canadian counterparts, most of these bands played a mix of traditional Celtic tunes—including the group dance number “The Siege of Ennis”—as well as popular American songs played with a jazz or swing feel. For many recent Irish immigrants, however, the appeal of traditional Irish dance, or ceílí, music remained strong, and many believed that it was more common in Roxbury than it was back home.

As thousands of fans swarmed the postwar dancehalls, a growing commercial market developed for local artists. Irish music recordings had been available in Roxbury since 1926, when Justus O’Byrne DeWitt opened his House of Music store near the corner of Dudley and Warren Streets. A combined record store and travel agency, he also offered music lessons and instruments. With the boom in Irish dance music in the late forties, Dewitt started his own record label, Copley Records, and produced dozens of recordings by local Irish and Canadian bands. Sales were aided by Boston-area radio shows such as the Irish Radio Hour on WVOM, hosted by Dudley Street shopkeeper Tommy Shields.

Following its heyday in the 1940s and 1950s, the Dudley Street dancehall scene gradually faded. A drop off in Irish migration, demographic change and growing racial tensions in Roxbury, and changing musical styles of the 1960s all drove patrons away from Dudley Street. After a decline in popularity in the 1960s and 1970s, Celtic music would revive in a somewhat more intimate form, moving to smaller clubs and pubs. But the earlier era of the Dudley Street dancehalls was a critical part of the city’s musical heritage, one that delighted several generations of fans and helped preserve elements of traditional Celtic music that still survive in Boston today.

Works Cited

Burrill, Gary. Maritimers in Massachusetts, Ontario, and Alberta: An Oral History of Leaving Home. Montreal: McGill-Queens’s University Press, 1992.

Ferrel, Frank. Boston Fiddle: The Dudley Street Tradition. Rounder Records, 1996.

Gedutis, Susan. See You at the Hall: Boston’s Golden Era of Irish Music and Dance. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004.

“Restoring the Hibernian,” Boston Globe, March 14, 2004.