The Hyde Square neighborhood of Jamaica Plain has been home to generations of immigrants from Europe and Latin America. In 2018, it was officially designated as Boston’s Latin Quarter. Photograph courtesy of Hyde Square Task Force.

Sharp contrasts characterize the neighborhood of Jamaica Plain (JP) today. Working class Spanish-speaking and Black communities reside along its north and east edges, where bodegas, botanicas, and rental apartments line bustling streets. They live a world away from most of JP where the middle and upper classes own expensive condominiums and stately homes near the serene Jamaica Pond. JP’s diverse population, and its disparities of wealth, status, and spatial distribution are part of a long history of economic change, immigration, and discrimination.

In the 1600s, the British colonialists who settled in what became JP appropriated from the Massachusett natives the arable land, timber, stone, and brooks that facilitated the growth of farming over the next two hundred years. Soon, the area’s attractive expanse of verdant hills and the 60-acre Jamaica Pond charmed the rising elite of Anglo-Saxon families, whose wealth was based on the international trade in slaves and commodities such as rum and opium. Envisioning JP as a bucolic retreat, they built elegant mansions where they cultivated a lavish life style. That privileged life rested on an entourage of Irish immigrant workers.

19th Century Immigration

Fleeing poverty and famine, the Irish started settling in JP in the 1830s and 1840s. They worked as unskilled labor in a variety of jobs hauling goods, in husbandry, and as teamsters. However, it was the wealthy estates that offered the most stable employment. The Irish constructed the buildings, did the housework, tended animals and gardens, and looked after children. It is estimated that over two hundred Irish women served the needs of the offspring of estate owners in this period. The hard-working Irish faced social and religious prejudice, and they lived in poverty. The disparity between rich and poor is evident in the extremes of two cemeteries that were both established in JP in the 1840s. In the rolling Forest Hills Cemetery, the affluent Anglo Saxons came to rest in limestone and marble family mausoleums; the Catholic poor were buried in the modest and crowded Tollgate Cemetery.

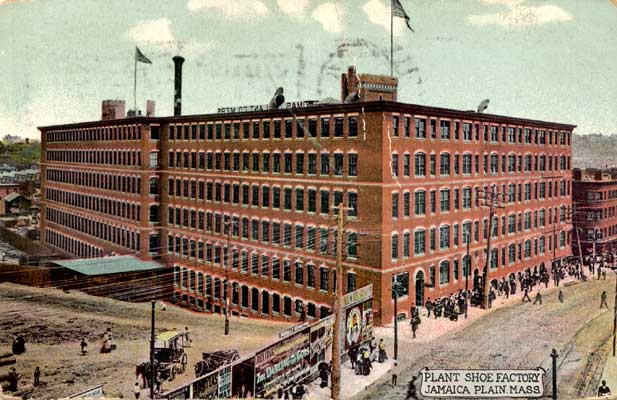

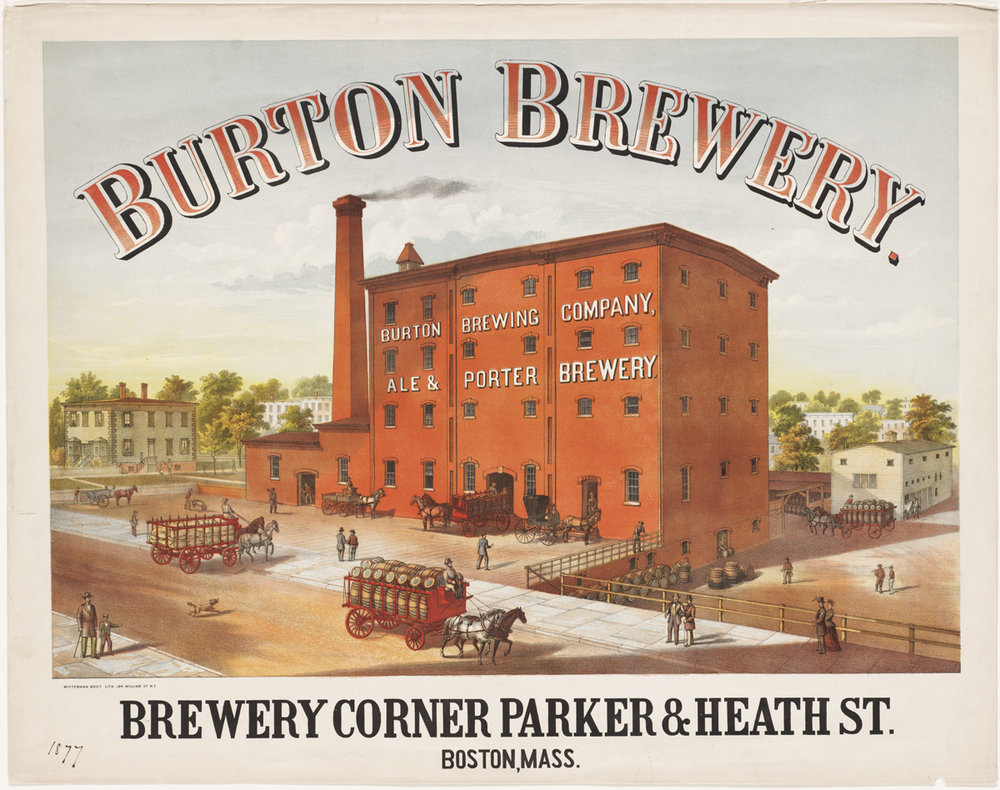

With the beginning of trolley car service in 1856, JP began its transformation from a farming area into an urban town with commerce, manufacturing, and professional services. Factories producing fans, dye, chemicals, gas, transport equipment, baseballs and other commodities were established along Green Street; in the Stony Brook valley, there were 24 breweries operating by the 1870s. By the end of the century, JP was not only the center of the New England beer industry, it was home to the largest shoe manufacturer in the United States, the Thomas G. Plant Company, which by 1913 employed more than five thousand people, half of whom were women.

Immigrants were woven into every aspect of JP’s robust 19th century development. Ireland continued to be the main country of origin, and by 1880 the Irish comprised 25 percent of JP’s heads of household. Most worked in the factories. The lives of the Glennon family were typical of many Irish in JP: men worked in the breweries and women in the shoe factory. Other Irish immigrants joined the middle class as proprietors of shops and bars, like Dennis Doyle, who opened Doyle’s saloon in the factory district where it soon became a center of Irish sociability and political life. A few became wealthy: the richest person in JP was Patrick Meehan, who made his fortune in construction, real estate, and industry and became influential in Democratic Party politics.

Germans formed the second largest group, and in 1880 they comprised 14 percent of household heads. Unlike the Irish, the majority of Germans in JP were Protestants from urban middle-class backgrounds. They brought formal education, business and professional experiences, and sometimes financial connections with Germany. Best known as the owners and skilled workers of JP’s breweries, German immigrants were also tradespeople, professionals, and highly skilled artisans such as piano makers. They kept German language and culture central in their lives through the Boylston Schul-Verein society , founded in 1874, which played a part in the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s formation (Mozart and Schiller Streets in Hyde Square are another legacy of this German musical influence). Although their languages, social clubs, and churches were distinct, German and Irish immigrants were not isolated from one another. They lived in the same neighborhoods around Hyde Square and Stony Brook, their stores were side by side, and the well to do Irish invested in the German beer companies. In addition, Germans and Irish often worked in the same breweries, albeit in different jobs and unions.

Decline and Revival

The first half of the 20th century brought changes. Although people from Canada, Greece and Italy settled in JP, the numbers of foreign born fell overall. German immigration stopped with World War I, and European migration slowed with the restriction laws of the 1920s. The economy also shifted as Prohibition shut down the breweries, the shoe plant closed in the 1950s, and other factories moved to the suburbs, as did many children of immigrants. By the late 1950s, once thriving businesses and residential neighborhoods had deteriorated.

In the 1960s, Spanish speaking immigrants started to bring new life to JP after the US government resettled Cuban refugees in the once Irish and German-dominated Hyde Square. Cubans were soon followed by larger numbers of immigrants from the Dominican Republic. Many Dominicans in JP have roots in Miraflores, a small Dominican village with which they have retained strong familial ties. Living amid Puerto Ricans who also settled in the neighborhood, Dominicans and other Latino migrants formed a cohesive and dynamic community that has fostered civic and cultural activities through the Hyde Square Task Force and other organizations. Through their efforts, the Hyde Square/Jackson Square area was designated as Boston’s Latin Quarter by the Massachusetts Cultural Council in 2018.

Since the late 1990s, however, fast-rising property values and gentrification have brought increasing economic pressures on JP’s foreign-born population. Many have been priced out of Hyde Square, and businesses once serving Spanish-speaking people have been replaced with those catering to affluent newcomers. Nevertheless, immigrants are still a critical part of the Jamaica Plain community and make up just under a quarter of its population today.

–Deborah Levenson

Works Cited

Burke, Gerry. “Doyle’s Talk,” Jamaica Plain Historical Society, 2005.

Douglas, Jen. “From Disinvestment to Displacement: Gentrification and Jamaica Plain’s Hyde/Jackson Squares,” Trotter Review, 23:1 (2016).

Levitt, Peggy. The Transnational Villagers. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Lyons, Helga M. “Boylston Schul-Verein and the German Saturday School,” Jamaica Plain Historical Society, 1999.

Rogovin, Janice. A Sense of Place: Jamaica Plain People and Where They Live. Boston: Mercantile Press, 1981.

Steele, Susan. “Shoes & Brews: An Irish Family in Jamaica Plain, 1880-1940,” Jamaica Plain Historical Society, 2020.

Von Hoffman, Alexander. Local Attachments: The Making of an American Urban Neighborhood, 1850-1920. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994.