Billares Colombia, a pool hall near Central Square, is a popular gathering place of Colombians in East Boston. Photo courtesy of Jorge Caraballo.

Arriving in growing numbers since the 1980s, Colombian immigrants represent the second largest immigrant group in East Boston. Called “Little Colombia,” by some, the neighborhood has become the heartland of Colombian settlement in Boston, with roughly three-quarters of the city’s Colombian population. Whether through the many businesses that line the streets, the homes of immigrant families, or the cultural institutions they have created, Colombians have helped to revitalize the neighborhood and have worked to make it a vital Latino community.

Migration

While a small number of Colombians came to Massachusetts in the 1960s and 1970s, the emergence of East Boston’s Colombian community began in the 1980s. Political violence had ravaged Colombia since the onset of La Violencía in 1948, a prolonged conflict between the two main political parties that killed or displaced tens of thousands of people over the next two decades. The unrest deepened in the 1980s, as guerrilla groups such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) battled government forces, and violent drug cartels took hold in the region around Medillín. The widespread violence, together with economic restructuring programs that devastated the economy in the 1990s, spurred many Colombians to emigrate.

Prior to the 1980s, many Colombians coming to the US were from the working class. Since then, economic dislocations led growing numbers of middle-class and professional workers to emigrate as well. Over the years, the percentage of undocumented immigrants also rose, as violence and extortion forced some to flee for their lives. The American Community Survey suggests that Colombian migration to East Boston has slowed somewhat since the 2008 recession, with population estimates of Colombians in the neighborhood falling from 4176 in 2007 to 3638 in 2014.

Many of those settling in East Boston came from areas in and around the capital city of Bogotá, as well as from Medellín, where the drug wars took their highest toll. About an hour’s drive north of Medellín, the small town of Don Matías has been a particularly popular sending area. Neighborhood residents in fact joke that there are now more Don Matíans in East Boston than in Don Matías itself.

The recent history of the town helps explain why so many of its residents relocated. A small agricultural town, Don Matías witnessed a bitter struggle between rich and poor within the local Catholic Church in the mid-1960s. Eventually there was violence, a wealthy man was killed, and many of the elite families moved away. With the economy failing and few job opportunities, poorer residents of Don Matías made the journey to Massachusetts to find work, with many coming to East Boston.

Settlement

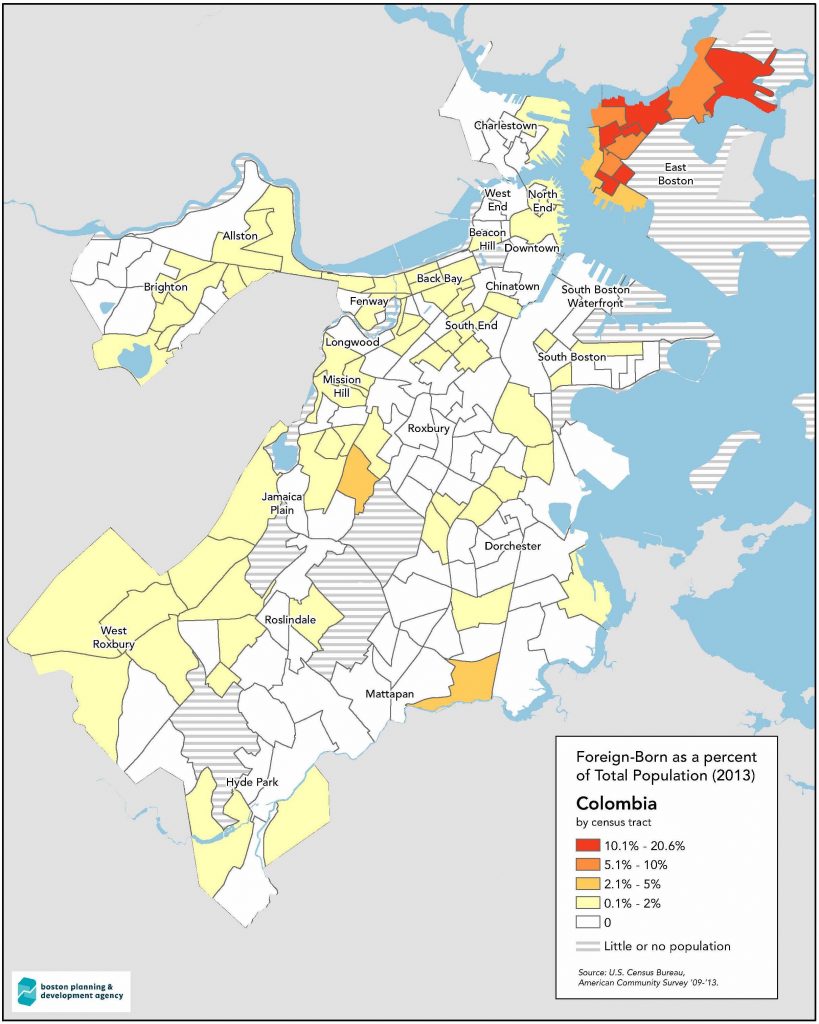

Exactly why Don Matíans and other Colombians decided to settle in East Boston is hard to determine, but their growing concentration in the neighborhood is undeniable. The 2000 Census found a majority (58 percent) of the city’s foreign-born Colombians living in East Boston. By 2014, the American Community Survey found that fully three-quarters of the city’s 4851 Colombian immigrants lived in Eastie, suggesting a growing concentration. Back in the 1980s, there was already an established community of Puerto Ricans in the neighborhood and a growing population of Central Americans. Having a sizeable Spanish-speaking population no doubt made Colombians’ adjustment to the city easier. Jobs in local garment and textile plants—ailing but not yet closed—probably attracted Colombians who had worked in similar industries in and around Medellín, a major textile and garment-making center. Likewise, East Boston’s relatively affordable rents and its easy access to the MBTA made it easier for newcomers to live and commute to jobs in other parts of the city.

As with earlier European immigrants, the abundance of triple-decker housing in East Boston also facilitated chain migration. As Colombian families purchased triple-deckers in the neighborhood, they often rented the two other apartments to family and friends from their homeland. As the accompanying map shows, Colombian residents and homeowners are heavily concentrated around Maverick Square, in Orient Heights, and in Eagle Hill and Day Square in between. No other neighborhood in Boston hosts such a sizable and concentrated Colombian community.

Education and Occupations

Colombians in Boston have had typically lower rates of educational attainment compared to the native born. From 2000 to 2013, the percentage of Colombian immigrants age 25 and older earning high school degrees increased from 28 to 45 percent, a significant improvement. But those completing bachelors or graduate degrees has remained below average at 17 percent in 2013, compared to 29 percent for all foreign born and 52 percent for the native born. These low levels reflect the lack of access to affordable secondary education in Colombia as well as limited opportunities for higher education in Boston.

Lower educational attainment has contributed to the concentration of Colombian workers in lower-paid service jobs. According to the 2000 Census, Colombians in Boston were overrepresented in service occupations with over 40 percent working in that area, compared to only 25 percent of the total foreign-born. This overrepresentation has increased since then; according to the 2009-2013 American Community Survey, 68 percent of Colombians worked in service occupations, compared to 48 percent of all foreign-born.

Despite these limitations, Colombians in East Boston have had great success as retail and small business owners in a predominantly Latino neighborhood. Across the city, Colombians have a higher share in self-employment, with almost 10 percent being self-employed, compared to only 7 percent of the foreign-born and only 6 percent of the native-born population, according to the 2013 American Community Survey. Many of the Colombian-owned businesses in East Boston were the product of years of hard work doing other jobs to save up for starting a business. This was the path of one prominent local business owner, Amelia Sanchez, owner of La Sultana Bakery.

After arriving in Boston from Bogotá in the 1980s, Amelia worked in the factories and would sell her baked goods in a food truck at soccer games on the weekends. Although she was not able to attend high school in Colombia, Amelia saved her money, and in 1993 she and her husband opened La Sultana Bakery in Maverick Square. Since then, La Sultana has become a symbol of Colombian immigrant success, and Amelia herself has become a pillar of the community, whom people come to for help and guidance. It is one of the first businesses Colombian newcomers go to when looking for work and has become a meeting place in the community.

La Sultana is just one of dozens of Colombian-owned businesses that have sprung up in East Boston. Businesses like Mi Rancho Restaurants, Billares Colombia (a pool hall), Marlen Beauty Salon, Café Gigú, and Traditional Asian Healing Arts, were all founded by Colombian immigrant entrepreneurs and have developed a strong Latino customer base. Some cater specifically to Colombians or Don Matíans, attracting customers from across the Boston area. These businesses have contributed to the economy of East Boston, providing employment, as well as neighborhood vitality and stability.

Social and Religious Organizations

Colombian immigrants sustain their culture through local religious and cultural organizations. One such organization in East Boston is Bajucol, a group that performs traditional Colombian folk dances, such as kumbia and bambuco at city events. Miguel Vargas, a Colombian immigrant who moved to Boston to attend Northeastern University, founded Bajucol in 1995. The group consists of young dancers and mimes from Colombia as well as second-generation Colombian American youth from East Boston and surrounding areas. The group provides a way for young immigrants to maintain their Colombian identity and culture, while also mentoring youth in a sometimes challenging environment. As Vargas explained, Bajucol was founded to promote a positive representation of Colombian culture and to fight the drug stigma that hung over the community in the nineties. “We are trying to change the image of Colombians. The group promotes the culture of Colombians, the talent, and the good citizens in the East Boston area” (Diaz, 2005). It also helped familiarize the larger community with Colombian immigrants and what they represent, which is important in order for them to be understood and to be successful.

Perhaps the biggest event bringing the community together is El Festival Colombiano, celebrating Colombia’s Independence Day in mid-July. Founded in 2009, the festival includes Colombian food, crafts, music, dance and other cultural events. During its first seven years, it was held in different areas of East Boston, but in 2016 the festival moved to City Hall Plaza, where it hosted more than ten thousand Colombians and other visitors from across New England.

Although Colombians have not formed their own service organizations, they have contributed to some of Eastie’s pan-Latino organizations, such as the East Boston Ecumenical Community Council (EBECC). Founded to aid immigrants and refugees in the 1980s, EBECC evolved into a neighborhood-based organization that promotes the advancement of Latino immigrants of all ages through education, services, advocacy, community organizing, and leadership development. Hernan Rodríguez, a local Colombian entrepreneur, is a teacher there who recognizes EBECC’s importance to the community. As a teacher, Hernan helps Latino immigrants learn English but also gives them guidance and support. He remembers being in their position when he arrived in the 1980s and says that the most important thing for him “is to work with the community and to give back what I have been given in the past.”

Another way Colombians contribute to the pan-Latino community is through their faith. Founded by Irish immigrants in the 1840s, Most Holy Redeemer Catholic Church began serving Colombian and other Latino immigrants in the 1980s, with Spanish masses every Sunday. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Father Robert Hennessey was the pastor of Most Holy Redeemer Catholic Church as it became a predominantly Latino parish. Fluent in Spanish, Father Hennessey helped to bridge the cultural gap and was always quick to help immigrants find jobs. Even during Sunday mass, he would make regular announcements when newcomers were looking for work. During the four Spanish masses held on Sundays, it was standing room only because so many Latino immigrants would attend. Most Holy Redeemer is more than just a place to pray, it also serves a social purpose, where people can find services and assistance and discuss community affairs.

An alternative to going to Most Holy Redeemer Church for some Colombians, and specifically those from Don Matías, is to watch live streams of religious services from the town church in Don Matías. This act shows not only their strong dedication to their faith but also their commitment to their homeland.

Transnationalism and Integration

Colombians in East Boston have worked to integrate themselves into American society while also maintaining connections to their homeland. A key way they stay connected is through remittances sent to their families back home. According to a 2002 estimate, each Colombian household in Boston on average sent back $256 per month. In addition, many stay connected through frequent phone and video calls and follow Colombian politics and cultural life through Spanish TV and the internet.

Because so many local Colombians hail from Don Matías, there have been particularly strong connections with that town. In recent years, in fact, Don Matías’ economy has been rejuvenated via remittances from East Boston immigrants. “The economy of Donmatías is based on pig and cow farming, textiles and the remittances that people send from the United States,” said former mayor Liliana López. “Those who have migrated invest a lot of money in the town and have a strong influence in the political decisions we make.” The transnational ties that many have with their hometown are so strong that Adrian Cadavid, a Don Matían who owns Café Gigu in East Boston, worries that many eventually will leave Eastie. Moreover, the 2017 peace accord with FARC and efforts at restorative justice might encourage some migrants to return in the future.

For many, though, East Boston has become home and they are intent on staying. This sentiment is evident in the roots Colombians have planted in East Boston by buying homes and businesses and creating their own community. In a University of Massachusetts study of Latino Business Owners in East Boston, many that were interviewed said they did not think about moving back to Colombia because they had created strong roots here and saw themselves as full and active citizens of both East Boston and the US.

Amelia Sanchez has no plans to return to Colombia for a number of reasons but among the top are her children and La Sultana Bakery. As her daughter explained (translating for Amelia), “I feel like I have grown a lot and changed a lot of lives. I have become much stronger because in Colombia there is a lot of machismo and things like that but here there is the feminist movement, and I feel a lot stronger than I would have if I stayed in Colombia.” Amelia has been able to develop a new identity as an immigrant woman, which has afforded her new possibilities realized through her children and La Sultana Bakery.

Hernan Rodriguez has also chosen to stay in Boston. “In comparison to where I lived in Colombia, this is heaven. There is no comparison in other words.” Hernan has also been able to live openly in East Boston as a gay man. The culture of the US has afforded him greater liberties in expressing himself and being comfortable in his own skin. It is through this new acceptance that he has been able to succeed in his business and in life in East Boston.

For more recent and less economically successful immigrants, however, the hope of staying in East Boston is not assured. As new development and gentrification have taken hold and rents have soared, many Colombian families have been displaced or are facing eviction. Given these challenges, it is unclear whether East Boston will remain a Colombian stronghold or if efforts to stabilize the neighborhood will allow Boston’s Little Colombia to survive and thrive in the years to come.

–Colleen Hyland, Boston College ’16

Works Cited

Abraham, Yvonne, “Making Their Statement,” Boston Globe. May 2, 2006.

Borges-Mendez, Ramon, Michael Liu, and Paul Watanabe. Immigrant Entrepreneurs and Neighborhood Revitalization: Studies of the Allston Village, East Boston, and Fields Corner Neighborhoods in Boston. Malden, MA: Immigrant Learning Center, 2005.

Boston. BRA Research Division and the Mayor’s Office of New Bostonians. Imagine All the People: Colombians in Boston, 2011.

Boston. BRA Research Division and the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Advancement. Imagine All the People: Colombians, 2016.

Caraballo, Jorge. “‘Donmatías, Massachusetts.'” Medium (blog), December 9, 2015.

—East Boston, Nuestra Casa. Medium (blog), April 11, 2017.

Diaz, Johnny, “The Silence of the Limbs,” Boston Globe. May 29, 2005.

Garcia, Marcela,”Her Style’s Taken Root: How an Immigrant-owned Salon Embodies East Boston’s Revival,” Boston Globe. July 15, 2013

Interview with Hernan Rodriguez by Colleen Hyland, East Boston, October 17, 2016.

Interview with Amelia and Jennifer Sanchez by Colleen Hyland, East Boston, October 17, 2016.

McDonald, Michele, “Deepening Roots Like the Irish and Italians Before Them, Eastie’s Latinos are Forsaking Homeland Dreams to Move from Renting to Owning–Homes, Businesses, Even Burial Plots,” Boston Globe. December 1, 2002.

Ordonez, Franco, “Colombians Press for Protected Status Proposed Legislation Renews Hope for Many Seeking to Stay in US,” Boston Globe. September 14, 2003.

Shenoy, Rupa, “A Struggling Colombian Village is Revived in East Boston, But It Could Soon Fade Away,” WGBH News. April 26, 2016.