In 1899 the Boston Herald reported on what was likely one of the first Syrian restaurants in the city. Located somewhere near Oxford Street, it was a small basement-level eatery with no sign out front. Described as “hidden” down alleys or in tenement basements, early Syrian restaurants like this one were surrounded by an air of mystery typical of Bostonians’ views of the “Near East” and its Arab peoples.

In 1899 the Boston Herald reported on what was likely one of the first Syrian restaurants in the city. Located somewhere near Oxford Street, it was a small basement-level eatery with no sign out front. Described as “hidden” down alleys or in tenement basements, early Syrian restaurants like this one were surrounded by an air of mystery typical of Bostonians’ views of the “Near East” and its Arab peoples.

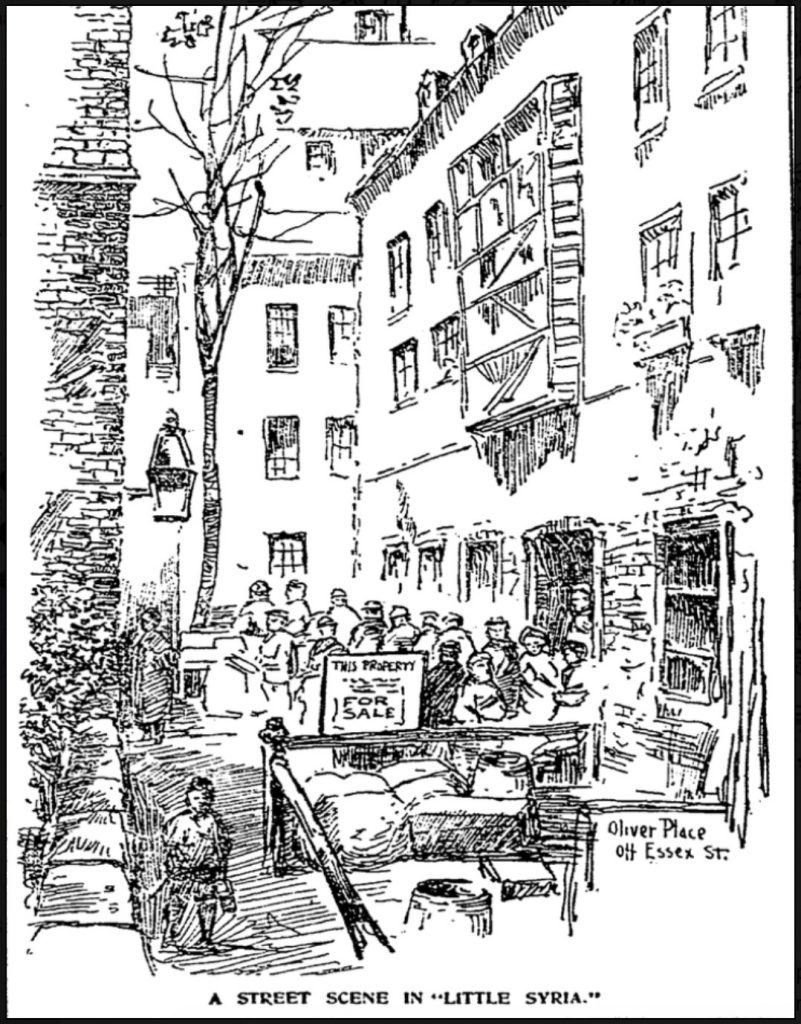

Spotty newspaper accounts over the next decade mentioned Syrian restaurants on Oliver Place, Beach, Oxford, and Hudson Streets (today’s Chinatown). At the time, such establishments were interspersed with those run by Chinese, Greeks, Armenians, and other groups settling in the South Cove area. The Syrian restaurants were noted for their family-owned character and hospitality. “Syrians are noticeably hospitable,” said a Boston Herald writer in 1903, “even when a casual stranger calls upon them sweetmeats are offered, and always accepted.” Syrian people, he added, were proud of their heritage and eager to share their native recipes with visitors.

What’s For Dinner?

Some of the notable dishes served in these establishments included koosa—a squash stuffed with rice and meat—roast lamb, and yabrak (stuffed grape leaves). Another American writer visiting a Syrian restaurant in 1903 favorably reported on the kibbe, which he described as “a strange compound of chopped lamb, many spicy things, some grainlike substance [likely bulgar], all made into a cake and fried.” Although native Bostonians typically found these foods unappetizing or “uncouth in appearance,” they often changed their tune once they tasted them—as one put it, “most delicious.” Many patrons opted to top off the meal with a strong black Syrian coffee.

These early restaurants were concentrated in the area known as Little Syria, overlapping and adjacent to Chinatown, where Syrian/Lebanese immigrants had been settling since the late 1880s. While our 1895 map does not show any Syrian restaurants at that time, by 1926 we found five, including three in Little Syria (see map). This is just a tiny fraction of the 57 licensed Syrian-owned restaurants in the city that year (see chart). Many of those restaurants likely sprung up in the South End, along Shawmut Avenue where the Syrian/Lebanese community had expanded to by the 1920s and 1930s.

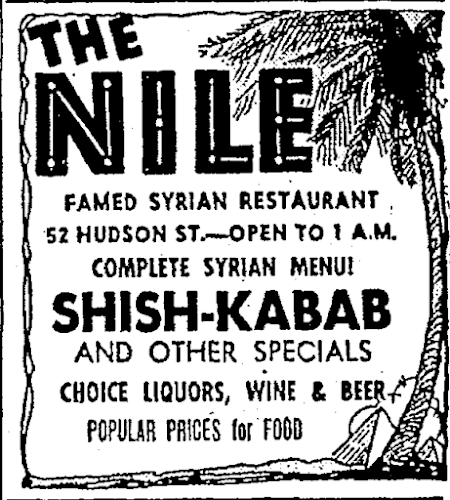

The Nile Restaurant

Perhaps the most legendary Syrian restaurant in Boston was the Nile. Started by the Salem family in 1934, the Nile was a small restaurant located at 52 Hudson Street. Born in Beirut around 1890, the owner, Deeb G. Salem, immigrated to the US in 1908 and worked in restaurants, including as a cook and pastry chef in a resort in upstate New York. During the Depression, Salem and his wife Rose, also from Lebanon, opened their own small restaurant in Boston’s Little Syria. Rose did most of the cooking, with their son John running the barbeque, and Deeb making desserts. The Salem family lived a block away, and initially most of their customers were from the neighborhood.

The Nile served an array of Syrian dishes but was especially known for their kharouf mihshee (stuffed barbequed lamb) and lamb mishwi (or as it would later be termed “shish kabob”—lamb cubes skewered with vegetables and grilled), while Deeb’s baklava was a popular dessert. As more native-born Bostonians discovered the Nile, the Deebs also began serving cocktails and American dishes to appeal to a broader clientele. In the 1940s and 50s, advertising for the restaurant highlighted motifs of camels, palm trees, and pyramids to play on Americans’ fascination with the Middle East.

Open from mid-morning to 1 am, the Nile was a fixture on Hudson Street for nearly thirty years. But the building of the Massachusetts Turnpike Extension in the 1960s was a catastrophe for the Salem family, as it was for other Syrian/Lebanese families still living on Hudson Street. As the state demolished much of the neighborhood, the Nile moved to a new location on Broadway Street in Park Square in 1964. In the process, they expanded significantly, with three dining rooms and an adjoining “Harem Lounge”– furnished with flying carpets, murals of Babylonian themes, and oasis-like palm trees and waterfalls. Unfortunately, the family did not enjoy the lavish new facilities for long; Deeb Salem died just two years later, and the Nile closed soon after.

With the demise of Little Syria and the redevelopment of the South End, Syrian restaurants dispersed across the region. Today, they can be found in places like West Roxbury (where many Syrians and Lebanese resettled), as well as in suburbs like Quincy, Norwood, and Watertown. The styles of Middle Eastern cuisine have also diversified as new immigrants from Armenia, Egypt, Iran, and other countries have opened eateries across greater Boston. Today foods like shish kabob, hummus, and pita bread are losing their “ethnic” status as they become familiar staples at local tables and grocery stores.

–Peyton Brown, Mohsin Kazim, and Lauren Sichel

Works Cited

“Among the Boston Syrians. Peculiar Customs of the Race.” Boston Herald, August 30, 1903.

“As Cooked in Syria.” Boston Herald, July 18, 1899.

Auffrey, Richard. “Chinatown, Little Syria and its Restaurants,” The Passionate Foodie, September 1, 2020, and “The Nile: The Most Famous Restaurant this Side of the Pyramids,” September 8, 2020.

Elie, Rudolph. “Adventures in Eating: The Syrian Place,” Boston Herald, November 1, 1951.

“For Near East Foods, Try the Nile,” Boston Herald, June 28, 1964.

“How Boston Syrians Make Themselves Real Americans.” Boston Herald, November 2, 1924.

“The Nile: Middle East Oasis,” Boston Globe, September 27, 1964.

US, World War II Draft Registration Card, Deeb George Salem, Ancestry Library Edition.