Corner of Belgrade Avenue and Aldrich Street in Roslindale, 1899. Courtesy of Roslindale Historical Society.

A residential and commercial community known today for the many ethnicities of its shop owners, Roslindale is part of the shifting landscape of neighborhoods and immigration in southwest Boston that was once a section of colonial Roxbury. Following independence, elite Yankee Protestant entrepreneur families such as the Welds and Atwoods found Roslindale’s rolling hills, forests, and the Stony Brook waterway and valley an ideal location. They established expansive estates, complete with orchards, pasture for sheep (whose wool supplied Lawrence mills), and farmlands that provided agricultural goods to communities along the new Boston and Providence Railroad line.

The first 19th century immigration to the area provided the cheap labor for these holdings. Born in Ireland in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Irish women and men fleeing the potato famine came to Roslindale as field and stable hands, blacksmiths, domestics, and other skilled and unskilled workers. Testimony to their presence are Irish surnames–such as O’Brian and Cahill–on the headstones of the small Tollgate Cemetery near Forest Hills, established in the 1860s to meet the needs of these immigrant Catholics. The numbers of Irish immigrants grew in the 1870s as a consequence of renewed depression and of political persecution of Irish nationalists. For many, Roslindale offered opportunities: S. W.C. Canniff, a stonecutter who came from of County Cork, Ireland in the 1880s, used granite from nearby Quincy to start what is today W.C. Canniff’s & Sons Monuments. More generally, the Irish found work in a variety of trades, and they stayed in the area. Numbering over 2300 towards the end of the century, they were the largest foreign-born group in Roslindale.

At the center of their community was the new Sacred Heart Church, established in 1893 by Father John Cummins—for whom Cummins Highway was named—a popular figure who spoke alongside William Lloyd Garrison in support of Irish Home Rule and helped put Roslindale on the map of Boston’s Irish politics. As elsewhere, once an ethnic community prospers, more immigrants settle there. One hundred years later, Irish-born priest Father Gerry O’Donnell would be giving mass and hearing confession in Gaelic at Sacred Heart for the newly arrived from the west of Ireland, where Irish is still widely spoken.

With Boston’s annexation of Roslindale in 1873, the area developed as a “garden suburb,” where residents could escape the city’s crowded neighborhoods and industrial areas. Improved train transportation also made Roslindale more accessible. Sunday day trippers arrived to picnic on its bucolic slopes in the Arnold Arboretum, established in 1872. The Boston Herald advertised Roslindale as the “choice outlaying district.” Doctors recommended it to TB patients for what was known as the “climate cure. “ By 1890 the Yankee estate owners had gone into real estate, clearing tracts of land that were then sold in parcels for building well-to-do residences as well as more modest homes.

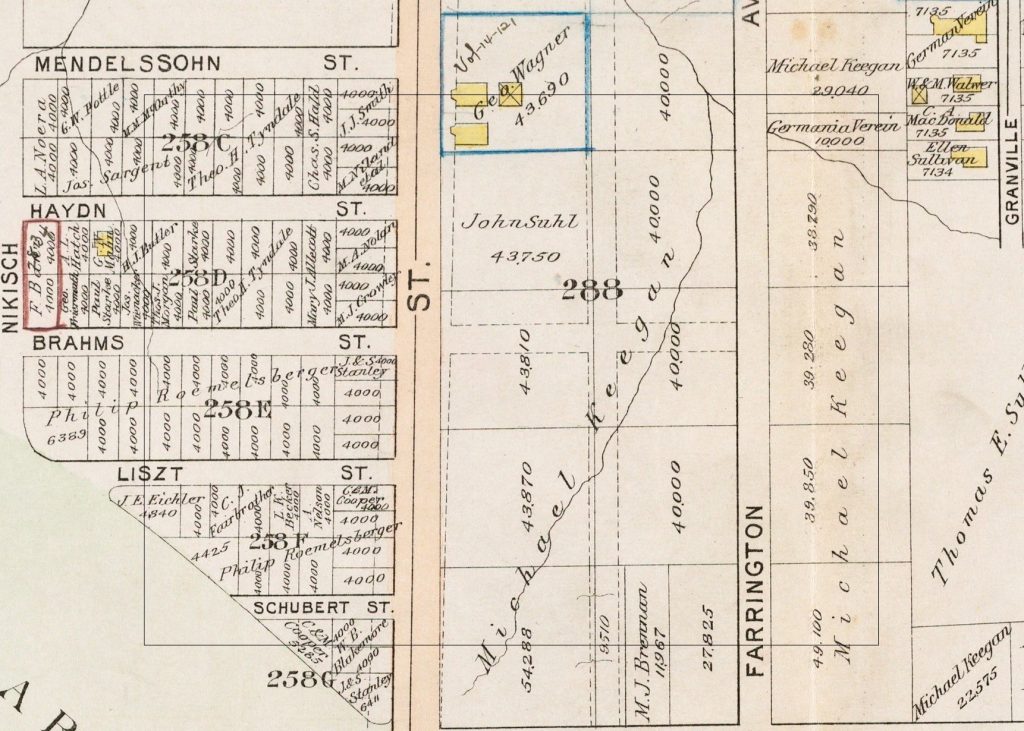

Soon many first and second-generation immigrants settled on the neighborhood’s tree-lined streets, put in gardens, and often raised small farm animals in their yards. Although British Canadians, Germans, and Italians were all part of this movement, the latter two made deep inroads. Of the roughly one thousand Germans who lived in Roslindale by the 1870s, most were Protestants who came with business experience, formal education, and professional skills. Their financial resources allowed them to establish Germania Hall (a German cultural and community center), open the German Lutheran Church on Kitteridge Street in 1887, and promote classical music and German language. Smaller numbers of Italians arrived toward the end of the century, and they too brought skills and culture–especially opera. But fleeing abject poverty, they brought fewer financial resources. They often found work in construction or clearing land, while others used their wits and artistic talents to earn a living.

Throughout the twentieth century Roslindale was a middle and working-class neighborhood. The German immigrant presence faded, while that of Italians and Irish remained steady without significant increase. Although the percentage of foreign born was less than in other areas of Boston in the 1900s, Greeks and Arabic speaking Syrian-Lebanese settled there, especially in the wake of World Wars I and II and military coups in the 1960s and 1970s. Primarily Catholic, they enriched the area with the churches and festivals of Eastern Orthodoxy, along with their bakeries, repairs shops, and small groceries.

When Roslindale businesses and property values took a dive in the 1970s, largely due to the spread of shopping centers and the racialized fears of busing that led to “white flight,” it was immigrants who revived Roslindale. In addition to Greeks and Syrian-Lebanese, Haitian and Dominican professionals and workers began to arrive in the 1980s, settling along Washington Street and adjoining blocks south of Forest Hills. Often well educated, Haitians brought their island culture and the buoyancy of a tight-knit community evident in worship centers such as Eglise Baptiste du Tabernacle, multiple Kreyol language professional services, and the vigor with which they have organized relief for recurring crises back home.

Dominicans, along with smaller groups of Colombians and Central Americans, have broadened use of the Spanish language in the neighborhood and introduced Latino music to its streets. Opening bodegas, barbershops, and other small businesses, Dominicans have been part of the rejuvenation of Washington Street, one replete with a mural of David Ortiz, Manny Ramirez, and Pedro Martinez, Red Sox stars from the Dominican Republic.

By 2000 Roslindale was becoming, once again, renewed as an immigrant place. The remarkable shift in the percentage of Hispanic and non-white population, from 23 percent in 1990 to 53 percent in 2010, is largely the result of immigration. As of 2016, the foreign born made 29 percent of Roslindale’s population, a higher percentage than the city overall. The neighborhood’s diversity is especially evident in the vicinity of Roslindale Village–or the Square as many residents call it–where merchants hail from Albania, Algeria, China, Colombia, Dominican Republic, England, Ghana, Greece, Guatemala, Jamaica, Japan, Haiti, Hungary, Italy, India, Lebanon, Senegal, Syria, Venezuela, and Vietnam.

–Deborah Levenson