Italian American families gather in a home shrine in East Boston, 1951. Leslie Jones, courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library.

Italian immigrants were the largest and arguably the most important immigrant group in East Boston for much of the twentieth century. In the early years, Italians faced a daunting set of barriers, including discrimination, low education levels, and little room for upward mobility. Over the next few decades, they would become the dominant ethnic group in the neighborhood before moving out in the second half of the twentieth century. Italian immigrants and their descendants thus played a critical role in shaping East Boston and its history.

Migration

In 1875, there were only a dozen Italians residing in East Boston, which was largely an Irish neighborhood at the time. Most Italians started coming to East Boston after 1895, escaping economic hardships in Italy or overcrowding in Boston’s North End. The Massachusetts Census reported over 4,500 foreign-born Italians living in East Boston by 1910. That population rose to over 10,000 by 1920, more than a quarter of all Italians living in Boston at the time. The foreign-born Italian population peaked in the 1920s, but the children of Italian immigrants increased the Italian-American population in the neighborhood for several more decades.

Most Italians who came to the US were from southern Italy, and the make-up of East Boston was no exception. In a sample of World War I draft cards of East Boston men, the majority listed birthplaces in provinces of Calabria and Sicily. A much smaller percentage came from northern Italy, mainly from Liguria and Abruzzi.

Overall, two out of every three Italians coming to the US were working males in search of jobs and wages to send back to Italy. This gender imbalance was largely because Italian social norms did not permit single Italian women to migrate to the US by themselves. It was only after finding work and some sense of financial security that Italian men would send back for their wives, children, or extended family. This male-dominant pattern was evident in East Boston, but to a lesser extent. According to the federal census of 1910, Italian men in East Boston outnumbered women 58 percent to 42 percent. In the North End, there was a much greater gender disparity, with the majority of the population consisting of young, single Italian men. After finding a spouse or job, it is likely that some of these men moved to East Boston as their second place of settlement.

Italians were more likely to be married than other foreign-born populations in East Boston, and there were fewer female-headed Italian households compared to other immigrant groups. This was partially due to the lower number of independent female immigrants, but also because of the strong patriarchal structure that was engrained in Italian culture.

Italian migrants to East Boston also had larger households. The average Italian household in the early 1900s held twelve residents, a higher number than other immigrant groups in the area and more than the average North End Italian household. Housing may have been a factor here. East Boston was known for its triple-decker houses, often lodging at least three families. The triple-deckers provided housing and additional rent payment from the other two floors, allowing homeowners to cover their mortgage while creating living space for extended family. These multigenerational houses facilitated chain migration and allowed for greater economic security. Many Italian immigrants also took in boarders to help pay the rent, contributing to the crowded living conditions.

John Christoforo’s multi-generational upbringing in East Boston was one example of such households. Being raised with not only his immediate family, but also with his paternal grandparents and uncle’s family was a common experience for East Boston Italians, John explained. His paternal grandfather, who came to the US in the early 1900s, arrived as a single young man and lived in an apartment in the North End with other single men. After marrying, he and his wife moved in with John’s grandmother’s family in a triple-decker home in East Boston, a pattern common among many young Italian couples.

Settlement

As with other immigrant groups, chain migration and homeland connections led Italian immigrants to cluster together in several areas of East Boston. Italian immigrants strove to maintain their culture and heritage, but they also sought protection in what was still an Irish-dominated neighborhood. Fearing that new immigrants would compete for local jobs and housing, some Irish residents were hostile and unwelcoming towards the newcomers. Consequently, it was safer for the Italians to live in Italian-dominated streets.

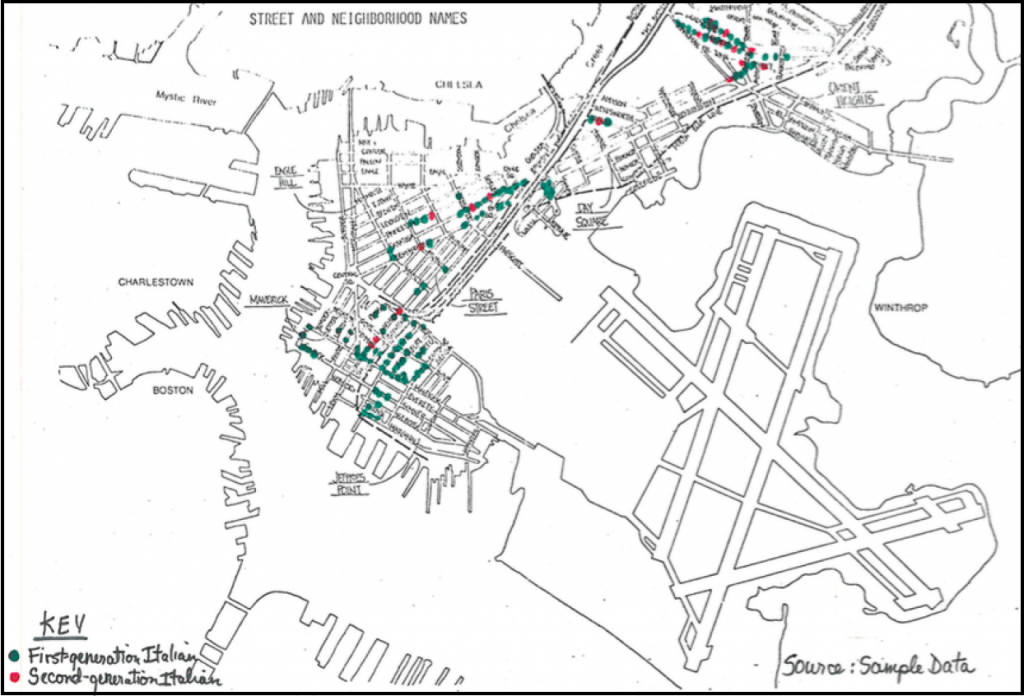

Using federal census data from 1900, Abigail Franklin created a map of Italian settlement (see below) showing distinct clusters of households. A study by settlement house worker Albert Kennedy in the 1910s confirms Franklin’s findings, showing that Italians in East Boston settled in two primary areas, with growing clusters between the two. The largest settlement was around Maverick Square and Jeffries Point, situated predominantly on Cottage, Summer, Havre, and Decatur Streets. The area started to grow in 1904, with over 1400 families that grew to roughly 10,000 residents a decade later. Initially, Italian residents moved here from the North End. Leaving a virtually Italian-only section of Boston was certainly a risk, but rent was lower, especially for larger homes needed for families. And it was still close to the city center. Once this beachhead of settlement developed, many immigrants started coming directly to East Boston from Italy, mainly from Sicily and Calabria.

The second largest settlement was located in Orient Heights. This more prosperous section was situated near the top of a hill, and Kennedy’s report recorded a population of roughly 1500 to 2000 Italians at the time. While there were some residents from southern Italy, the majority of immigrants who lived in Orient Heights came from northern Italy. The neighborhood contained somewhat larger homes and housed a more prosperous population of store owners, saloon keepers, and skilled workers.

In between these two clusters, another emerging area of Italian settlement was located north of Bennington Street stretching up toward Eagle Hill. Kennedy explained that early pockets of settlement began here along Princeton and Lexington Streets but later merged, and Franklin’s 1900 map shows a similar cluster of Italian households west Day Square.

After immigration restriction measures were implemented in the 1920s, the number of foreign-born Italians coming to East Boston gradually slowed. Nonetheless, second and third generation Italian Americans continued to spread out over East Boston beyond the initial settlements. By the mid-twentieth century, much of East Boston had become predominately Italian American.

Occupations and Education

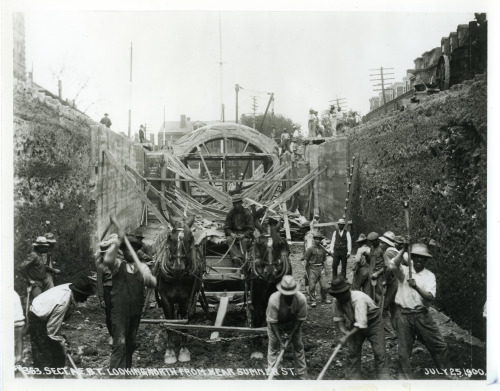

In general, most Italian immigrants who came to the U.S. worked low-wage jobs as manual laborers, providing a source of cheap labor for construction and manufacturing industries. In 1900, 14 percent of East Boston Italian workers were unskilled laborers, employed primarily in pick-and-shovel labor or on nearby farms. Another 23 percent worked in semiskilled jobs, while 54 percent were skilled manual workers. Only 10 percent worked in positions that had no manual labor.

A sample of World War I draft cards of men in East Boston shows a mix of manual labor and skilled trades. The most common occupation was laborer, followed closely by shoemaker. Other common occupations included tailor, butcher, blacksmith worker, cotton mill worker, mechanic, barber, and storekeeper. Interestingly, less than half of the sampled men actually worked in East Boston, despite claiming residence there. Many traveled to factories and shops in other parts of the city such as South Boston and Jamaica Plain, or to neighboring towns such as Everett, Winthrop, and Chelsea.

In the early twentieth century, education was not a priority for most East Boston Italians. Franklin’s study shows that in 1900, only 56 percent of Italians in the neighborhood could read or write. Although the education and literacy rates did increase over the years, low high school participation rates due to youth employment continued, and there were very few Italians who received a post-secondary degree. For girls, restrictive gender norms prevented many from pursuing further education or skilled professions. If they did work, it was usually in East Boston’s garment shops or cotton mills.

John Christoforo, who has a college degree, a handful of masters degrees, and a Ph.D., is the first to admit that he was the exception–that higher education was not a top priority for East Boston Italian Americans. John spoke highly of his father’s passion and belief in education as the key to upward mobility. While John’s father pushed him to go to a private high school, he remembers that many of his childhood friends who went to East Boston High School did not end up graduating, dropping out due to lack of interest, economic necessity, or involvement in gangs. This lower rate of educational attainment and mobility meant that East Boston would remain a “zone of emergence” for Italians for a longer period of time than for most other migrant groups.

Religion

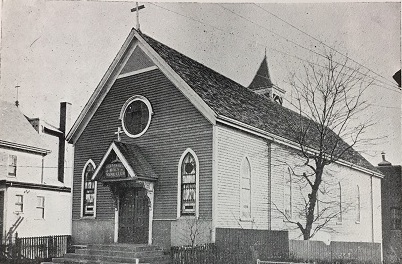

Like the Irish immigrants before them, Italian settlers arrived in East Boston with a strong sense of religious identity from their home country. Almost all Italians identified as practicing Roman Catholics, and religion was an important way to retain their Italian heritage. Over the course of the twentieth century, Italian immigrants built up several ethnic parishes in East Boston. Additionally, many Italian families practiced their faith at home, with elaborate Catholic shrines to patron saints of their hometowns and villages.

Italian Catholicism was, however, different in practice than Irish Catholicism, and at first the two did not mix well. In practice, Italian Catholicism in the early 1900s was described as “boisterous and expressive,” marked by vibrant festivals, parades, and celebrations. This was very different from the more traditional practices of the Irish Catholics, and initially created tension with the Boston archdiocese. To help accommodate the newer immigrants, the archdiocese allowed Boston area Italians to form parishes where they could follow their own traditions and practices.

The first Italian parish in East Boston, St. Lazarus, was founded in 1892 by a group of northern Italian families in Orient Heights and run by the Missionaries of St. Charles Borromeo (Scalabrinians), a religious order that served Italian immigrants across the Americas. Thirty years later, a new church was built on Ashley Street, which still stands today. On the other side of the neighborhood, Our Lady of Mount Carmel, a Franciscan-run parish, opened in 1905 to serve the predominantly southern Italian population of Jeffries Point. As Eastie’s Italian population grew, other formerly Irish parishes such as Most Holy Redeemer and Sacred Heart also added masses in Italian and served growing Italian-American congregations.

After World War II, however, the Italian population began to decline, as did attendance at local parishes. In 1985, St. Lazarus merged with St. Joseph’s, a once mainly Irish American church around the corner. In 2004 the Boston Archdiocese ordered the shutdown of Our Lady of Mount Carmel parish in a string of closings across the greater Boston area. Longtime Italian American parishioners fought to save the church, occupying the building and appealing the decision for more than a decade. But in 2016, the archdiocese finally sold the church property to a housing developer.

Politics

When Italian immigrants arrived in East Boston, Irish residents already had a stronghold in neighborhood politics. Irish political organizations largely prevented East Boston Italians from accessing elective office, while barriers such as poor literacy and education levels, return migration, and a lack of community cohesion contributed to low levels of voting and political participation.

Despite their absence from electoral politics, East Boston Italians organized many associations and social clubs that served to bring the community together. In the early years of Ward 2, a group of Italian immigrant business owners formed an Improvement Association to develop the neighborhood. Also in the early 1900s, a group of East Boston Italians organized the Mazzini Club, which regularly met to study and discuss both Italian and American politics. Another important social organization that is still around today is the Order of the Sons of Italy in America. A national organization, the first lodge in Massachusetts was founded in 1910, followed by dozens of others in the New England area. John Christoforo, a member of the Order of the Sons of Italy, says that there used to be a large East Boston base for the order, and that his own predecessors were members as well.

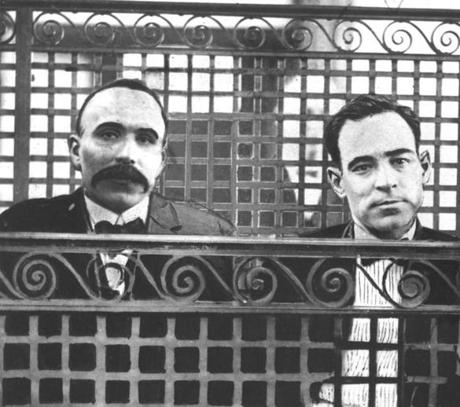

Radical politics were also evident in Boston’s Italian communities. One notable example was Gruppo Autonomo. An anarchist cell active in East Boston in the 1910s and 1920s, the group challenged US involvement in World War I and opposed capitalist oppression of workers. Two of its core members, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, both foreign-born Italian immigrants, were convicted and executed for two murders in a highly controversial case. Their questionable execution in 1927 prompted uproar within the local Italian community as well as national and worldwide protests.

As the twentieth century progressed, Italian Americans found growing success in electoral politics. After World War II, the Irish-Italian feud had quieted down, and Italian Americans began winning seats in the city council and state legislature, including representatives from East Boston.

Leaving East Boston

From the 1920s to the 1970s, East Boston was the city’s new Little Italy–with more Italian Americans than the North End. But in the years after World War II, the Italian population began to decline. During these years, suburbanization and upward mobility enabled younger Italian Americans to move out of East Boston to nearby communities such as Revere, Winthrop, Everett, and Saugus. The decline in the Italian population was especially evident by the 1980s when new migrants from Latin America and Southeast Asia began arriving.

In 2015, less than fifteen percent of documented residents in East Boston self-reported as being of Italian descent, while Italian immigrants made up only three percent of the population. Nevertheless, the small pockets of Italian Americans in the neighborhood still own local shops and businesses and keep the culture alive through church communities, festivals, and Italian heritage celebrations. Although no longer a dominant presence in the community, Italian immigrants contributed culture, businesses, and religion to make East Boston what it is today.

–Olivia Hussey, Boston College ’16

Works Cited

East Boston City Council. East Boston Planning Survey Report. Boston, 1915.

Franklin, Abigail. “Immigrants and Urbanization: East Boston’s Italian in 1900.” Senior Honors Thesis, Wellesley College, 1975.

Interview with John Christoforo by Olivia Hussey, October 3, 2016.

Kennedy, Albert J., and Robert A. Woods (1962). The Zone of Emergence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1962, repr. 1969, 187-219.

Levenson, Michael. “Boston Archdiocese Sells Closed Eastie Church for $3m.” Boston Globe, September 3, 2015.

Puleo, Stephen. The Boston Italians : A Story of Pride, Perseverance, and Paesani, from the Years of the Great Immigration to the Present Day. Boston: Beacon Press, 2007.

U.S. 1917 World War I Draft Registration Cards, Ancestry Library Edition.

U.S. Census reports, 1900-1940. Ancestry Library Edition.

Watson, Bruce. Sacco and Vanzetti: The Men, the Murders and the Judgment of Mankind. New York: Viking, 2007.