Homes and businesses along Marginal Street (ca. 1900-1910) across from the docks in East Boston, where many Irish laborers lived and worked in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Courtesy of the City of Boston Archives.

The development of East Boston in the 1830s coincided with the rise of Irish immigration to the city. The newcomers quickly became the dominant immigrant group in Eastie and remained so for the remainder of the nineteenth century, helping to build its infrastructure, churches, and political institutions. When the Irish moved out in the twentieth century, the neighborhood and its institutions would be inherited by new groups of immigrants, but the patterns established would blaze the trail for those who followed.

Migration

Even before the Great Famine of the 1840s, East Boston was a neighborhood that attracted Irish immigrants. The first child of Irish parents was born on Saratoga Street on November 17, 1833. With the onset of the potato famine in 1845, the Irish population of East Boston grew rapidly. This was especially true after 1854 when the start of ferry service allowed Irish residents of the heavily populated North End to move across the harbor. According to the 1855 census, there were 3498 Irish-born people living in East Boston, making up 23 percent of the population. During the latter half of the nineteenth century, the Irish remained Eastie’s largest immigrant group.

The 1855 Massachusetts State Census provides some insight into early Irish migration to East Boston. In a sample of 230 East Boston residents born in Ireland or the children of Irish parents, 55 percent were male and 44 percent female. This gap likely reflects the greater number of men migrating in search of work. Overwhelmingly, though, the Irish lived in family households; 95 percent lived with spouses or other family members and three quarters of those families had children.

While little is known about the origins of Eastie’s early Irish settlers, a survey of World War I draft registration cards indicates that later migrants came from counties across Ireland. In the 55 cards sampled, West coast counties were the best represented, with the largest number coming from Galway (15), followed by Mayo and Cork (6 each).

Some Irish immigrants made one or more stops before coming to East Boston. Some went to England first, others traveled to the United States via Canada, usually stopping in Nova Scotia. These migration patterns were evident in the birthplaces of their children, which included Ireland, England, Canada, and Massachusetts. In some families, the oldest children were born in Ireland, the next in Nova Scotia, and the youngest in Massachusetts.

Settlement

The earliest Irish residents lived in homes on Everett, Sumner, Porter, and Marginal Streets. They settled along the coast and near the docks where “water frequently came up about their houses and flooded the cellars” (Kennedy, 197). The 1855 census revealed that Irish families settled in clusters, either in the same building or next door. Family and home connections likely no doubt facilitated this pattern.

Sixty years later, Irish settlement had expanded considerably. World War I draft registration cards showed that many of the Irish still lived near the shore and docks, especially on Sumner, Lexington, and Bennington streets and around Most Holy Redeemer Catholic Church. Eagle Hill also became a popular neighborhood for many working class Irish. But in the older neighborhoods north and east of Maverick Square, the Irish population had declined, replaced by newcomers from Italy and Russia.

More established and prosperous Irish and Irish American families settled in Jefferies Point and the area north of Neptune Road. According to one observer in 1914, the Irish who lived in St. Mary Star of the Sea parish on Moore Street were very highly regarded. He described them as “hard working, moral, careful, savings type of the second generation,” who formed “the backbone of sturdy, conservative, loyal, people” (Kennedy, 197). This description demonstrates the changing perceptions of the Irish and their children as they integrated into American society.

Occupations

In the nineteenth century, Irish laborers were critical to the development of East Boston as they drained the swamps and built wharves, roads and housing. A sampling from the federal Census of 1850 gives insight into just how prevalent Irish laborers were in East Boston, as 62 percent of the 27 men in the sample worked as laborers. The next most common occupation was carrier, a transporter of goods, at 11 percent. There were a few examples of skilled laborers, including a tailor, a pilot, and a carpenter. Of the 24 women in the sample, only 5 were listed as having jobs, with 4 working as domestics and the other as a seamstress. This trend could indicate a lack of unskilled jobs available to Irish women or that it was uncommon, particularly for married women, to work outside the home.

The importance of the Irish to the local labor force continued into the twentieth century. The World War I draft card sample indicated that many Irish men worked in heavy industry, including machinery, oil, iron, and coal. Additionally, jobs related to shipping and the maritime industry were common, with over 20 percent working in those fields. A majority were longshoremen, loading and unloading cargo ships. Many of the jobs were now outside East Boston, and the use of the ferry system was increasingly important. The most common job, however, was streetcar motorman. The rise in this occupation suggests that the Irish were moving into more skilled unionized labor, further demonstrating their upward economic mobility.

One notable Irish dockworker was James A. Burns. An employee of the Cunard Line for more than sixty years, he began working at the docks at age eleven in 1864. When he died in 1930, Burns was thought to be the oldest steamship employee. He was known in the community as “Dock Parson” because of his near constant presence. During the later years of his service, he was known to wed eight to ten couples a day at the docks. In all, it is believed that he wed more than a thousand immigrants upon their arrival in the United States.

Religion

One of the most notable contributions of the Irish to East Boston was the founding of Most Holy Redeemer Church. Catholics bought the meetinghouse of the Maverick Congregational Society, and after some remodeling it was reopened as St. Nicholas Church in 1844. Church membership in the following years illustrates the growing Irish population of East Boston during the famine years. In 1844, there were 58 baptisms at St. Nicholas. Five years later, there were 175 baptisms there out of 435 total births in East Boston. By 1854, the number grew again to 338 baptisms. These numbers point to the growing Catholic presence on the island and the prevalence of Irish families that were making East Boston home.

St. Nicholas was renamed Most Holy Redeemer Church in 1855. Since then it has been a critical part of the East Boston community, especially for immigrants. The Catholic Church served as gathering point for many Irish, providing a connection to homeland religion and values. It was an all-encompassing involvement for many. Kennedy wrote in 1910 that the “Irish Catholics of the island have developed a life of their own, parallel and more or less apart from the rest of the community” through the creation of many Irish Catholic programs and institutions, including “parochial schools capable of caring for practically all the girls and many of the boys; their solidarities, societies, and boys’ clubs” (198).

While this was a product of church’s active effort to fulfill societal needs, it was also a result of the “economic and religious antagonism of the Protestant community.” During the mid nineteenth century, East Boston was home to a large population of Protestant evangelicals, and tension between the two led to intolerance. Protestant children were taught to fear priests and nuns, and at one time, “it was claimed that there were cells in the cellar of the Church of the Most Holy Redeemer which were used to incarcerate Protestants” (Kennedy, 199). This fear and hatred in the early years shaped the perception of the Irish and of Catholicism, a sentiment that would endure for decades.

As the Irish fanned out across East Boston, they helped establish several other Catholic parishes, such as St. Mary Star of the Sea just north of Day Square (founded in 1864), Our Lady of the Assumption in Jeffries Point (1865), and Sacred Heart on Paris Street (1873).

Politics

Anti-Catholic and anti-Irish sentiments helped give rise to a strong tradition of Irish political mobilization in Boston in the nineteenth century. Responding to longstanding nativist currents dating back to the Know Nothing party of the 1850s and continuing in the Republican party after the Civil War, Irish Bostonians developed a political base in the Democratic party.

As the Irish population of East Boston peaked in the late nineteenth century, Irish American politicians became a dominant force in East Boston’s political scene. Up until 1890, East Boston had been a Republican stronghold. In that year, Ward 2 (the area south of Porter Street) became Democratic, and about a decade later Ward 1 (north of Porter Street) followed suit. This shift marked the transition from native-born Yankee leadership in the neighborhood to that of younger Irish Americans.

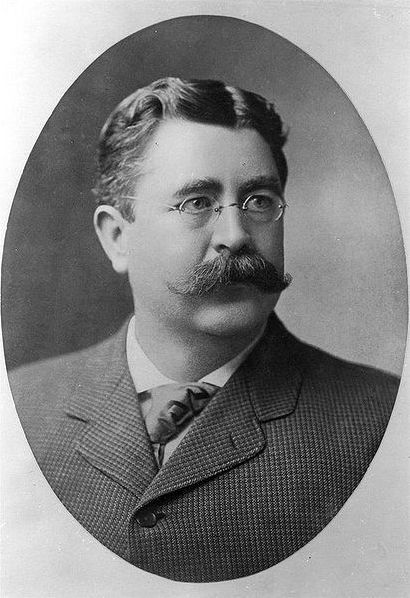

One of those young Irish leaders was Patrick Joseph (PJ) Kennedy who was born and raised in East Boston and got his political start on the waterfront. Born in 1858 to Irish immigrant parents, PJ came from humble beginnings. His father, Patrick Kennedy, was a cooper from Dunganstown, County Wexford and married his mother, Bridget Murphy in East Boston in 1849. Two cholera outbreaks left Bridget a widow and PJ the only male in the family before his first birthday. He received some formal education, but at fourteen, he left school to help support the family, finding a job as a longshoreman.

In the 1880s, he bought a saloon in Haymarket Square and after success there, bought another bar near the East Boston docks. He became further involved in the local liquor business by acquiring a bar in the Maverick House, a legendary hotel in Maverick Square. These business successes enabled him to buy a whiskey importing company, invest in coal, and purchase a large amount of stock in the Columbia Trust Company. His management of bars and saloons enabled him to garner political support, a common political tactic for the Irish.

Utilizing his businesses as launching points, PJ was the first Kennedy to enter the Boston and greater Massachusetts political scene. Beginning in 1884, he served five consecutive terms in the Massachusetts House of Representatives and was later elected to the state Senate. But PJ did not enjoy the campaigning and speechmaking. He was most known for his unofficial role as the political boss of East Boston’s Ward Two for more than thirty years. During this era, the ward boss was a key resource for working class Irish who were struggling to survive. As historian Robert Dallek described him, PJ was “likable, always ready to help less fortunate fellow Irishmen with a little cash and some sensible advice. PJ enjoyed the approval and respect of most folks in East Boston.” It was through this strong neighborhood base that he began to build the Kennedy dynasty that would later produce his grandson, President John F. Kennedy.

Exodus from East Boston

Beginning at the turn of the twentieth century, the Irish population began to dwindle in East Boston. Upward economic mobility, the arrival of newer immigrant groups, and intermarriage with non-Irish brought greater acceptance and encouraged the Irish diffusion across the city and suburbs. In the early twentieth century, it was common to move north across East Boston before moving to other areas, especially the flourishing neighborhoods of Dorchester and Roxbury. This migration was mainly among second and third generation Irish as they secured more education and higher paying jobs. It was this upward mobility of the Irish that particularly impressed settlement worker Albert Kennedy, prompting him to dub East Boston a “zone of emergence” on the eve of World War I. The example of the Irish, he predicted, would soon be followed by the Jews and Italians who were by then the dominant new migrant groups in the community.

–Daniele de Groot, Boston College ’16

Works Cited

Dallek, Robert, An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy, 1917-1963. Boston: Little Brown and Company, 2004.

Cullen, J. B. The story of the Irish in Boston, together with biographical sketches of representative men and noted women. Boston: James B. Cullen and Company, 1889. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015066420293

Handlin, Oscar. Boston’s Immigrants [1790-1880]; A Study in Acculturation (rev. ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1959.

“J.A. Burns Dead at Hospital Here, Employed for 60 Years by Cunard Line,” Daily Boston Globe, July 4, 1930.

Marchi, Rebecca. M. Legendary locals of East Boston, Massachusetts. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2015.

Woods, Robert A. and Albert J. Kennedy, The Zone of Emergence: Observations of the Lower Middle and Upper Working Class Communities of Boston, 1905-1914. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1962, 187-219. 1850

U.S. Census. Ancestry Library Edition.

U.S. 1917 World War I Draft Registration Cards, Ancestry Library Edition.

Massachusetts. 1855 State Census, Familysearch.org.