Procession of El Divino Salvador del Mundo (Divine Savior of the World) in Maverick Square, August 2016. Courtesy Divino Salvador del Mundo-Boston Facebook page.

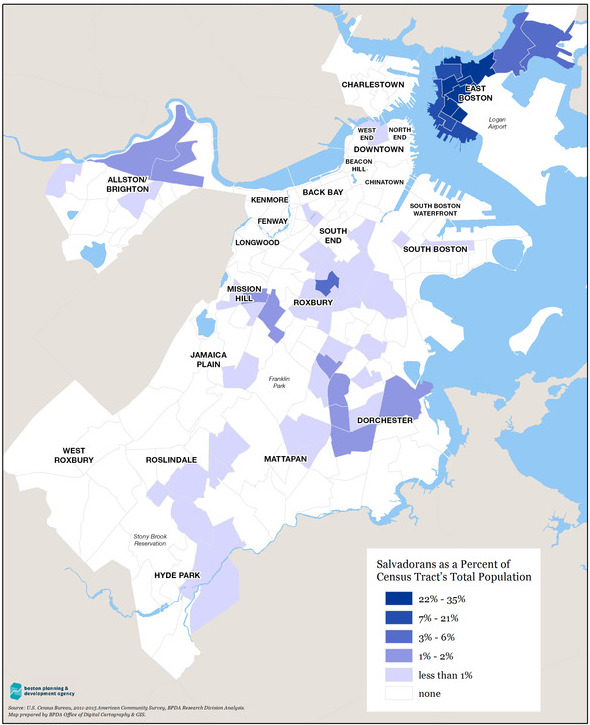

Over the past thirty years, Salvadorans have become the largest immigrant community in East Boston, while Guatemalans make up the third largest group. Migration to the neighborhood began in the 1980s, when the civil wars and violence in Central America caused thousands to flee. Since then, Eastie’s Central American communities have grown rapidly, contributing to a distinctive Salvadoran presence and a flourishing pan-Latino community evident in the neighborhood’s churches, businesses, politics, and cultural organizations.

Migration

During the 1980s, the escalation of war and violence in Central America led growing numbers of Salvadorans and Guatemalans to abandon their homes and flee to the US. In both countries, US-backed military regimes carried out a campaign of repression that led to mass violence and human rights violations against guerilla groups and civilians alike. Although the wars ended in the 1990s, emigration continued in face of a weak economy, the rise of violent crime and gangs, the separation of families, natural disasters such as Hurricane Mitch in 1998, and the growing demand for immigrant labor in many US cities including Boston.

East Boston residents Saul Perlera and Deysi Martinez both emigrated because of economic turmoil in El Salvador during and after the war. Fleeing the violence, Saul arrived in East Boston in 1986, noting, “it was the war and there were no opportunities… I didn’t see any future there for my family or any way of getting better. The United States was the logical place to go.” Arriving after the war, Deysi had similar reasons for coming to Massachusetts in 1997: “I said to myself, ‘here in the United States I could make money; I could make my home.’ And I couldn’t do that over there. I saw the reality of everyone in El Salvador; I didn’t have a future.” Saul and Deysi were typical of many Central Americans living in East Boston who were forced to flee their home countries because of the civil wars and their consequences.

Since the US did not grant Central Americans refugee status, many came as unauthorized migrants. Such journeys entailed danger and uncertainty as immigrants crossed the border “por tierra,” or by land, with the help of coyotes, or smugglers. After deciding to go to Massachusetts, Deysi and two of her siblings hired a coyote, who was her sister’s friend, and they paid him $4000, which included transportation, lodging, food, and two attempts to cross the border. For a month, Deysi and her siblings took buses and trains and walked across El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico to get to the United States. “When we were crossing [the US border], the most difficult part was the great walk in the darkness… you were walking and you didn’t know anything,” Deysi explained. “It was also very difficult having to sleep at night in between rocks, and we were also hungry after all the walking without being able to eat anything.”

Similarly, Saul crossed the border by walking from Tijuana to San Diego before flying to East Boston. According to Saul, who was sixteen at the time, this journey marked the end of his childhood. Although Deysi and Saul arrived in Massachusetts without documentation, both of them were later able to adjust their legal status. While such journeys ended well for some, others never reached their final destination because of injury, death, kidnapping, or arrest.

Settlement

When they began arriving in the early 1980s, Salvadorans and Guatemalans settled in established Spanish-speaking communities such as Jamaica Plain and especially Cambridge, where local churches offered sanctuary to undocumented war migrants. A smaller number went to East Boston, attracted by factory jobs, affordable rents, and an existing Spanish-speaking, mainly Puerto Rican community. By 1990, the US Census reported that 1452 Salvadorans, 248 Guatemalans, and 148 Hondurans were living in the neighborhood.

When they began arriving in the early 1980s, Salvadorans and Guatemalans settled in established Spanish-speaking communities such as Jamaica Plain and especially Cambridge, where local churches offered sanctuary to undocumented war migrants. A smaller number went to East Boston, attracted by factory jobs, affordable rents, and an existing Spanish-speaking, mainly Puerto Rican community. By 1990, the US Census reported that 1452 Salvadorans, 248 Guatemalans, and 148 Hondurans were living in the neighborhood.

Over the next decade, the abolition of rent control and rising housing costs drove many Central Americans out of Cambridge into nearby neighborhoods and towns. East Boston, with its affordable housing and proximity to downtown, became a popular choice, both for those already here as well new arrivals from Central America. Saul chose to settle in East Boston because his uncle already lived there. He moved in with his uncle’s family whose home served as a base for many of Saul’s arriving friends and family. By 2015 East Boston’s foreign-born Salvadoran population had increased to 8588, while its foreign-born Guatemalan population grew to 1469. Together, migrants from Central America and Mexico made up more than half of Eastie’s foreign-born population by 2015. For Salvadorans especially, East Boston has become a key area of settlement, housing 80 percent of the city’s Salvadoran immigrants.

Education & Employment

Educational barriers have been a serious problem for Central American immigrants. In Boston in 2015, 59 percent of foreign-born Salvadorans and 42 percent of Guatemalans had not completed high school, in contrast to 9 percent of the native-born population and 28 percent of the foreign-born overall. With respect to higher education, 16 percent of foreign-born Salvadorans and 27 percent of Guatemalans in Boston have attended at least some college, while only 8 percent of Salvadorans and 11 percent of Guatemalans have completed a bachelors’ degree.

Limited access to education in Central America helps explain the lower levels of education in these groups. According to Paula Virtue, a former ESL teacher in East Boston, Central American immigrants often “didn’t have access to a lot of formal education… [they] maybe had gone up to fourth or fifth grade, or some not at all.” In El Salvador, both Saul and Deysi had to move to larger villages in order to attend school, because during the Salvadoran Civil War, “teachers wouldn’t go to little villages because they would get shot.” Although Saul wasn’t able to finish high school in El Salvador, after moving to East Boston, he improved his English, got his GED, and began taking community college courses, which served as a stepping-stone to a career in real estate. For other migrants, though, long work hours and family commitments made it difficult to resume their schooling.

Regardless of the low levels of educational attainment, Central Americans have had high rates of participation in the work force. Most Central Americans have worked in service-related industries; such occupations employed 57.4 percent of Salvadorans and 55 percent of Guatemalans in 2015. Within the service occupations, the most common types of work have been building and grounds, cleaning and maintenance, and food preparation and serving. In addition to the service industries, Central Americans have also been overrepresented in blue-collar occupations in construction, extraction, maintenance, and transportation.

On the whole, these occupations have been unstable and offered low wages and few if any benefits. As a result, many of these workers and their families have struggled to survive. According to census reports in 2015, only 21 percent of Boston’s foreign-born Guatemalans and 14 percent of Salvadorans have reached a middle class standard of living, compared to 45 percent of the native-born.

For some Central Americans, however, small business has been a path to success in East Boston. For example, fifteen years ago, Deysi opened her grocery business, Estrellita Star Market on Meridian Street. While working as a waitress, she met the owner of a market who was selling the business. She was able to get a loan for $6000, which the owner accepted. After working seven days a week for a year and seven months without any help, Deysi was able to pay off her debt, and after a couple of years, she moved her market to a bigger storefront. Later, she and her husband opened a Salvadoran restaurant called Rinconcito Salvadoreño.

Saul also found economic success through starting a business. After working hard with multiple jobs seven days a week, he was able to open Perlera Real Estate in 2003. The stories of Deysi and Saul suggest how small business ownership in East Boston has facilitated economic advancement for Central Americans, just as it did for the Italians, Jews, and Irish before them.

Political and Social Organizations

One of the oldest organizations serving Central Americans in East Boston is the East Boston Ecumenical Community Council (EBECC). Founded in 1978 as a religiously based racial justice organization, EBECC has evolved into one of the largest community-based organizations for Latinos in Boston, providing education and legal services, advocacy, community organizing, and leadership development. With the prevalence of educational barriers for Central American immigrants, EBECC has offered programs that educate newcomers, helping them learn English and reach their larger goals.

Since their arrival, Central Americans have emerged as leaders in the area of immigrant and worker rights. A key activist group was Centro Presente, founded in Cambridge in 1981, which fought for immigrant rights and provided legal aid, ESL classes, and other services for Central American immigrants. In the twenty-first century, Centro Presente evolved into a membership organization for Latinos that focused on community organizing and leadership development and relocated its headquarters to East Boston. Working with Eastie’s Latino communities and those in nearby suburbs, Centro Presente has continued to fight for immigrant rights, sanctuary provisions, and economic and social justice.

The Salvadoran Consulate, located in East Boston, has also played a role in supporting immigrant rights. Originally located in Cambridge, the Salvadoran Consulate opened in East Boston in 2011. For the General Consul Jose Adgardo Aleman Molina, the new consulate was a “community achievement… the house for all Salvadorans in New England.” Among their services, the consulate has offered free legal consultations and hosted a Labor Rights Week to help Salvadorans learn about their rights and benefits as workers.

Religion

Religion too has played a significant role in the lives of Central American immigrants. For these groups, the church has been an important gathering place that has helped to create a sense of community in East Boston. The most popular religious traditions among Central Americans have been Catholicism and Pentacostalism. Churches in East Boston have offered services in Spanish to minister to these new groups. Among Catholics, Most Holy Redeemer Catholic Church near Maverick Square has the largest Central American congregation, with multiple Spanish masses on Sundays. The parish also features special Latin American devotions and celebrations. During the first week of August, Salvadorans celebrate the feast of their patron, the Divino Salvador del Mundo, (Divine Savior of the World). Maintaining their traditions, Salvadoran immigrants have celebrated the feast with a procession of Christ the Divine Savior through the streets of East Boston beginning at Most Holy Redeemer Church.

The church has acted as a communal space for Central Americans in East Boston, allowing them to feel at home in the community. A member of the Parish Pastoral Council, Deysi has been part of the spiritual movement of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal, which has held prayer groups at Most Holy Redeemer several days a week. According to Deysi, many Central Americans have been drawn to Most Holy Redeemer’s masses and prayer groups both for spiritual reasons and as a way to get acquainted with the community. Some newcomers have not “known anyone here,” Deysi explained, “so they have gone [to church] to get adjusted to the community and find a new life.” Moreover, in times of difficulty, East Boston church leaders have been open to dialogue between religions and have organized vigils in order to support the community and promote unity.

Cultural Life

Salvadorans and Guatemalans have found a home in East Boston that allows them to maintain their heritage and traditions. After arriving in Massachusetts, Deysi initially moved to Woburn with her father. She did not feel happy in the US, however, until she moved to East Boston. There, Central Americans and other Latinos surrounded Deysi, helping her feel more at home. With the abundance of Central American restaurants and grocery stores, Deysi has been able to maintain her heritage through access to Salvadoran products and food. In addition, Deysi highlights the prominence of cultural activities in East Boston, with many activities promoted by the consulate.

Some of these activities include the September celebration of Central American Independence Day by both Salvadorans and Guatemalans in Boston. Salvadorans also celebrate Massachusetts’ Salvadoran-American Day in August, which was officially recognized by Governor Charles Baker in 2015. That year, the New England Salvadoran-American Day foundation hosted a festival in East Boston’s Noyes Playground, complete with an appearance from the Salvadoran ambassador from Washington D.C., Salvadoran games such as “La Loteria de Atiquizaya,” and traditional music and dance. In addition to the festival, celebrations of Salvadoran-American Day have included a parade through the streets of East Boston, with appearances from Salvadoran music and dance groups, the winner of Miss El Salvador New England, Salvadoran soccer players from the Eastie Soccer League, and other recognized figures from the community.

As with several other newcomer groups, Central Americans have found a home in East Boston, sustaining their transnational cultures and forming a broader pan-Latino community locally. Recently, though, new development and gentrification have led to rising rents and displacement of many working-class immigrants. Whether the Salvadoran and Guatemalan communities of East Boston will survive these pressures remains to be seen.

–Andreina Baquero-Degwitz, Boston College ’16

Works Cited

Boston Redevelopment Authority, “Boston Population and Housing by Neighborhood Areas, 1980,” September 1983.

Boston Redevelopment Authority, “East Boston ‘29 Page Profile’ 1990 Census of Population and Housing,” March 1993.

Boston Redevelopment Authority, Imagine All the People: Guatemalans in Boston, 2016.

Boston Redevelopment Authority, Imagine All the People: Salvadorans in Boston. 2016.

“Divino Salvador Del Mundo,” Facebook page.

“El Salvadoran Consulate Opens with Fanfare,” East Boston Times-Free Press, August 21, 2011.

Interview with Deysi Martinez by Andreina Baquero-Degwitz, October 19, 2016.

Interview with Saul Perlera by Daniele de Groot, October 26, 2016.

Interview with Paula Virtue by Andreina Baquero-Degwitz, October 27, 2016.

Ospino, Hosffman. “Latino Catholics in New England,” in Latinos in New England. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006.

Uriarte, Miren, et al., Salvadorans, Guatemalans, Hondurans, and Colombians: A Scan of Needs of Recent Latin American Immigrants to the Boston Area, Gastón Institute Publications, 2003.