AFAB staff and board members, 2018. Courtesy of the Association of Haitian Women.

One evening in 1988, several Haitian women gathered in a Hyde Park basement to form a women’s study group. The women, ranging from recent college graduates to working professionals, had noticed a dismissive attitude toward young women involved with community organizations in their social and political circles. “We were in these meetings when we felt as if there was a need for us to have our own space,” recalls Carline Desire, the central organizer of the group’s first meeting.

The young Haitian women gathered called themselves the group Etid Fanm Ayisyen, or Haitian Women’s Study Group, and the basement became a space for them to voice concerns about their communities as well as specific issues relating to women. As they continued to meet and talk, the study group grew into an association dedicated to aiding Haitian women in Boston. With this small basement meeting in 1988, the Association of Haitian Women in Boston, otherwise known as the Asosiyayon Fanm Ayisyen nan Boston (AFAB), was born.

Similar to many Haitians immigrating to the United States in the latter half of the 20th century, Carline Desire followed her parents to Boston in 1975 after a political incident in Haiti compromised the safety of her family. While the journey to Massachusetts was a relatively simple one because of the fortunate economic situation of her parents, Desire and her brother faced challenges with racism and anti-Haitian sentiments as they settled into their new home and schools in Boston. This did not stop Desire from becoming involved in her various communities. She worked against South African apartheid in high school and later focused her activism on three separate Haitian organizations while a student at Boston University.

By 1988, when she first invited those five women to her parents’ basement, she was a recent college graduate with a wealth of organizing experience and growing concerns about Boston’s Haitian community. Those experiences and concerns were reflected in the ambitious mission of the association–that is, “to help empower women” in every way.

The Condition of Haitian Women

The Association of Haitian Women in Boston chose to work in the heart of Boston’s Haitian community, serving the residents of Dorchester/Mattapan. They operate from an office located on the corner of Fuller and Morton Streets in Dorchester, identified by a sign reading “KAFANM.” One meaning of this Haitian Kreyol phrase is “the condition of Haitian women.” Since its founding in 1988, AFAB’s primary focus in bettering the condition of Haitian women in Massachusetts centered around domestic violence. The prevention of and intervention in domestic violence became a “cornerstone of [AFAB’s] work” after the women in the group realized how prevalent the issue was in their community and even among themselves.

As immigrants subject to cultural differences and unfamiliar with the available legal protections in the United States, Boston’s growing community of Haitian women in the late 20th century were particularly vulnerable to entrapment in abusive relationships. These women suffered without knowledge that other Haitians were experiencing similar problems and without a trusted recourse for getting help. First, they set out to raise awareness of this issue in the Haitian community so that women could feel comfortable breaking their silence. This required an accessible community organization that could be sensitive to the cultural needs of Haitian immigrant women while simultaneously offering legal, economic, and personal resources.

The deaths of six abused Haitian women in the mid-1990s especially spurred AFAB into action. They responded by creating spaces for advocacy against domestic violence and developing networks of supporters such as the Codman Square Health Center and the Haitian Multi-Service Center. Informal concerns became official advocacy as the Association developed in the last decade of the 20th century. In 1997, for instance, AFAB hosted its first annual Domestic Violence Prevention Forum where community members and organizations gathered to develop collective responses.

As the decade came to a close, they also introduced monthly meetings with local clergy members, state workers, representatives from the district attorney’s office, and shelter organizations. Out of these meetings emerged an ongoing project called the Haitian Roundtable on Domestic Violence that developed collaborative prevention and intervention efforts.

As part of these efforts, AFAB launched its own anti-abuse intervention program in the mid-1990s. By 2002, the program counseled about 150 survivors of domestic violence, more than triple the number of women in need in 1998. AFAB based this program wholly on that initial ambitious mission to empower women, as they sought to develop survivors’ abilities to live independently through emotional rehabilitation and economic training. Acknowledging that “only [survivors] can make that decision [to leave]” AFAB members steered away from impelling abuse victims to leave their partners and toward addressing the larger issue of women’s entrapment in abusive relationships due to cultural expectations, economic limitations, and legal barriers.

The Home of Haitian Women

The phrase “KAFANM,” which adorns the operating center of the Association of Haitian Women can also be translated as “the home of Haitian women.” This translation reflects the organization’s concern about housing problems faced by Haitian women in Boston. “I remember we did a survey and housing was a major problem,” says Executive Director Carline Desire.

During the organization’s first three years, AFAB was still a small, volunteer organization without a home itself, pooling only the resources available to the young Haitian women directly involved. But in 1991, the group embarked on a journey to create a housing project for women and families, especially those affected by domestic violence. Lacking experience with housing development, AFAB partnered with the Women’s Institute for Housing and Economic Development to facilitate the planning process. Still, the project took five long years to complete as it faced many obstacles, including the opposition of the Dorchester community. “Why didn’t [the city] approve the project right away,” explains Desire, “It’s because people in the community didn’t want it.” While simultaneously expanding their advocacy against domestic violence, Desire and fellow AFAB volunteers met the opposition of their Dorchester/Mattapan neighbors with petitions drives along the streets affected by the impending project.

Eventually, the city approved the endeavor. The six-unit housing project attached to the main building of KAFANM finally opened in the late 1990s and began helping families to find their own economic footing. With the opening of the KAFANM building, AFAB itself now had a permanent home in Dorchester and flourished as a nonprofit organization. As it continued to provide needed housing and services to the Haitian community, Desire explained, “the same people who didn’t want the project became our friends.”

In the decade between the basement founding of the Association of Haitian Women and the establishment of its KAFANM headquarters, Carline Desire grew alongside her organization. Increasingly serious about her dedication to community involvement and to Haitian people, Desire pursued a master’s degree in community development at the University of Southern New Hampshire. She then delved into various jobs involving social work and teaching, even returning to Haiti to teach English in rural areas for four years.

When she returned to Boston in 1997, AFAB was transitioning to a paid staff, and Desire was asked to formally head the organization. This was a turning point in the organization’s history. With Desire taking the mantle of leadership as executive director–a position she still holds in 2019–the Association developed a paid staff, expanded its fundraising, and standardized its programming. All this began at a time when AFAB had only $200 in its bank account. Using donations, grants, and partnerships, the organization expanded its programming in the 21st century, promoting the success of Haitian women and their families through new adult education and youth development programs.

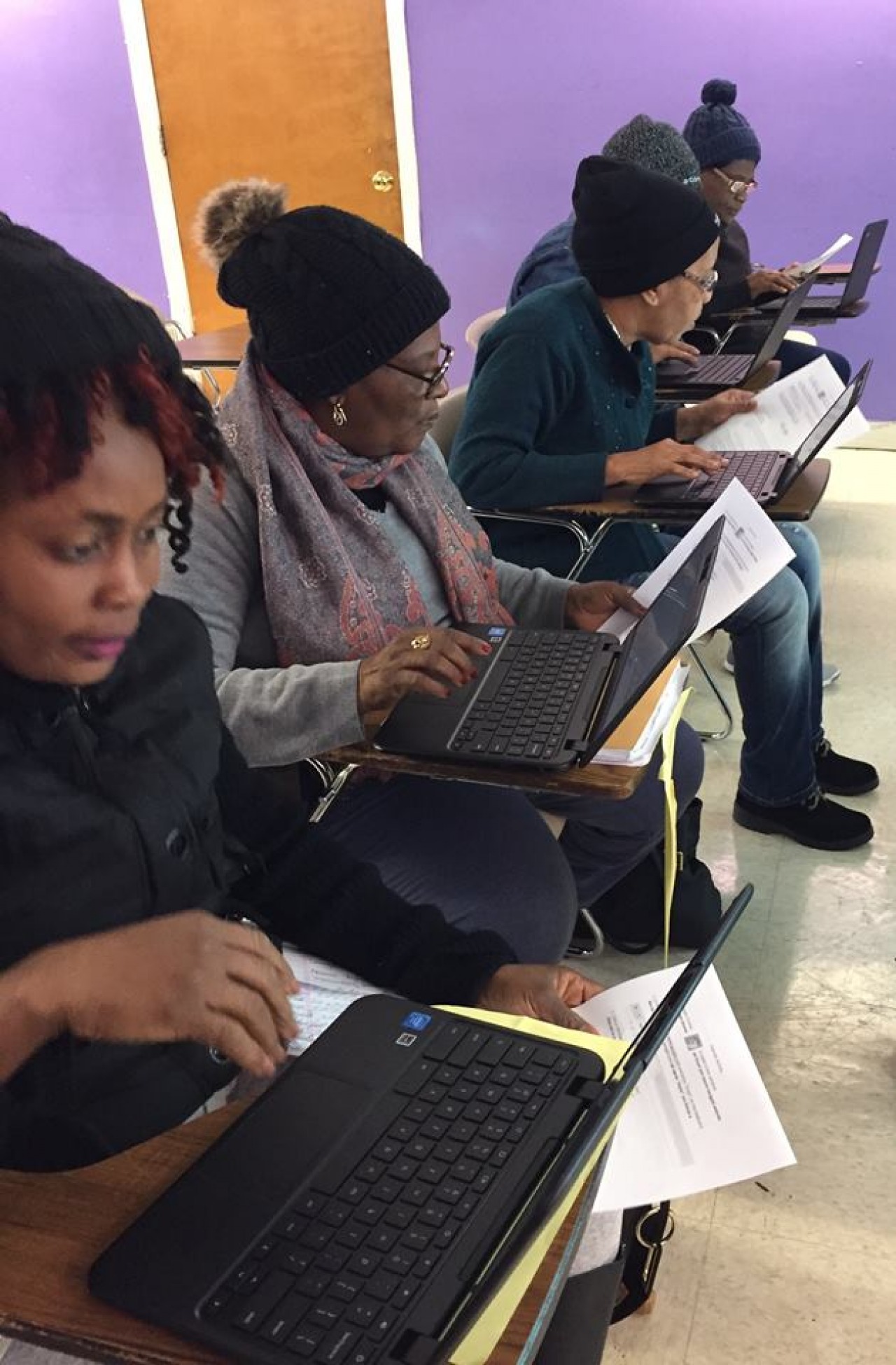

In 2001, for instance, the Association launched an economic literacy training program designed to enable and encourage financial planning among Haitian women. Maintaining funding for the program was a challenge, and it was later transformed into a computer literacy program in 2018. Courses on English as a Second Language, taught by members of AFAB, have also become an integral part of the organization’s mission. At the same time, AFAB’s dedication to furthering Haitian women’s economic and social integration is tempered by a need to “bridge generational and cultural gaps” within the community. Its youth development programs, therefore, sought to “maintain cultural traditions” through the French language programs and by teaching “poetry, music, drumming, and dancing, among other things.”

Despite a lack of second-generation Haitian women in the membership, AFAB continues to develop as a community resource and is currently seeking to expand its six-unit housing facility into a thirty-unit development. As Carline Desire puts it, the organization is “small in size but huge in impact.” Indeed, the Association of Haitian Women has used its thirty years of organizing and advocacy to gain a seat at the table for Boston’s Haitian community and for Haitian women in particular.

–Astride Chery, Boston College ’19

Sources and Further Reading:

Interview with Carline Desire by Astride Chery, Dorchester, MA, November 2018.

“Areas Haitians Look to Their Homeland.” Boston Globe, October 24, 1993.

Asosiyasyon Fanm Ayisyen nan Boston (AFAB). “AFAB-KAFANM Programs and Services.”

“Carline Desire’s Passion: Empowering Haitian Women.” Boston Haitian Reporter, 2011.

“Group Helps Fight Haitian Abuser.” Boston Globe, May 31, 2002.

“Haitian women build a rock-solid organization in Dot.” Dorchester Reporter, October 4, 2012.

“Haitians in Boston.” Boston Globe, August 29, 1971.

Radin, Charles A. “From Haiti to Boston.” Boston Globe Magazine, December 15, 1996.